By Maxime Chouinard

Note: This article was first published in the Fondation Napoleon’s newsletter of March 2021. Several people asked me for a translation, and since this blog is aimed at a different crowd, I chose to expand a little bit on some of the points I am exploring. I have been researching the question of French military fencing for close to 20 years now, and only now do I feel confident enough to put down some of the things I found. Thank you to Jean-Philippe Wojas for the proof reading, as well as Philippe Aguesse, Damien Olivier, Julien Garry, Phil Crawley and everyone who helped me with this research over the years.

Fencing is a martial art that has seen many upheavals in France. Its association with the culture of dueling has always earned it a mixed reputation, leading authorities to suppress it at times. In turn praised or despised during the Middle Ages, the masters of fencing nevertheless succeeded in raising the French School to the top of European fencing at the end of the 17th century, their style and their know-how being exported all over the continent and even beyond. The First and even the Second French Empire played an important part in the establishment of the French school, from Europe to America, and even as far as Japan.

Today in its Olympic, if not electric form, fencing has changed a lot, but many of its aspects would not be foreign to the fencing masters who served in the Grand Army. This article sets out to examine the practice of fencing in Napoleon’s army, its influence on the practice of dueling among the military, how the Grand Army contributed to extending the reach of French fencing far beyond its national borders, and how this process continued under the Second Empire.

The Ancien Régime and the Corporation

To fully understand the fencing practiced by the men of the Grande Armée, we must first examine what was practiced before it’s time, as several elements of the Ancien Regime’s fencing culture continued to be followed after the Revolution. Under the Ancien Regime, fencing was mainly managed by the Corporation of Fencing Masters based in Paris. This corporation saw to the certification of provosts and masters, but also to the repression of those called ferrailleurs, these unrecognized masters who operated illegally. The corporation then asked any master wishing to teach to submit to an examination which included assaults and demonstrations of skill with the sword, the sword and the dagger, the sabre, but also the halberd and the baton à deux boûts (lit. stick with two ends, ie: an iron shod staff) [1 ].

The teaching of these weapons, which to say the least are unusual in eighteenth-century France, is a matter of tradition, but probably also a way of blocking the road to foreign masters wishing to teach in the kingdom. Indeed, most Italian masters no longer practiced these weapons and therefore saw themselves at a disadvantage. This did not prevent these masters from teaching by other means, either by royal permission or through the various academies which operated somewhat outside the guild system. Its influence was also limited in colonies, such as New France, where certain fencing masters took up residence [2].

With the Revolution, the various guilds and corporations saw their privileges abolished, and that of the fencing masters was no exception. We then see the emergence of more decentralized structures. Learning continued to follow a certain relatively uniform structure, but was now rather based on the reputation of the master than on guild control. Structures were still forming, especially in the army, as we will see below. We see the appearance of diplomas, sometimes richly decorated, certifying a master or a provost. These certificates were sometimes given under the very general title of “fencing”, but more commonly they began to be awarded for particular specializations such as pointe, espadon, contre-pointe, la canne or le baton.

If at the beginning of the 18th century we only read of the pointe and the espadon, another style, or arme begins to appear around the middle of the century: the contre-pointe, which brings together the techniques of espadon mainly a style oriented towards cutting , and pointe, a style that only teaches thrusting techniques from foil practice.

The espadon is unfortunately described very little to us by the various French fencing treatises and manuals. Martin, Girard and Angelo only present the Espadonneur as an enemy to be faced, but sometimes their advice is enough to shed some light on the nature of this mysterious school. If the pointe is all in all fairly fixed at this time, it is quite another thing with the espadon, where is practiced either anachronistic styles reminiscent of the masters of the late sixteenth century, or versions very close to those practiced throughout the 19th century.

One fact remains however. The eighteenth-century French fencing master is much more interested in discussing pointe fencing, a style for which he is renowned throughout Europe. Whereas the sabre or the broadsword were wielded by the soldiers, but the latter do not yet enjoy the cachet they obtained under the Empire. All of the textbooks published at this time therefore deal with pointe.

The pointe: French pride

The most popular and well-known weapon in the French school is undoubtedly the pointe. This fencing developed mainly after the developments of Italian fencing as described by masters like the Venetian Giganti or the Paduan Fabris. In Giganti’s day, the rapier was the sword of choice. This weapon is then relatively long and heavy, at least in comparison with the swords which came to replace it. The style of fencing developed by these Italian masters lays a theoretical foundation which became a reference for the following centuries.

The fencer now retreats behind his sword, positioning himself at an angle in front of the opponent. His weight is carried on the back leg and his offensive technique relies first and foremost on a concept that isn’t exactly new, but at least never been so prevalent: the lunge. There is also a completely new nomenclature system for guards based on hand alignment. This is the beginning of prime, seconde, tierce and quarte guards to which will be added several more.

Italian and Spanish fencing were then at their peak of popularity. Fencing treatises competed in complexity to explain their actions, offering geometric diagrams as well as philosophical and physical concepts to make sense of their movements. But French fencing was slowly beginning to assert itself, along with the emergence of a new type of sword: the smallsword. This sword is a shorter, thinner version, with a more minimalist hilt than the rapier. Easier to wear, it gained popularity at court. It was adopted by the soldiers, and continued to be worn on the battlefield by many officers in the Empire.

The French fencing master brought two material innovations to the practice of fencing: the foil and the plastron. The foil is now an abstraction of the épée which allows a more energetic and safe practice, an invention which was decried by some masters who feared that the development of courage would be neglected, creating fencers who would flee at the first view of a sharp blade. This idea of developing courage is a common theme in fencing treatises and documents of the Renaissance, and one that would be worth investigating further in my opinion.

The plastron, which became a symbol of the master at arms, allows the latter to teach the lesson by fully developing the thrust on a moving and realistic target, removing many abstractions. Pointe fencing now focuses on one target in particular: the heart, one of the few targets that can end combat quickly. Surgeons of the time, like Ravaton, gravely reminded us of this, telling us that sword thrusts that affected the heart were simply never brought to the attention of the surgeon [3].

The development of the pointe generated an impressive number of treatises and manuals. The French masters had been relatively silent on the subject of fencing, leaving the subject to the German and Italian masters; this changed with the development of pointe fencing, which represented almost the entire French corpus in the 18th century.

However, this production was slowed down with the advent of the Revolution. Very few treatises were published until the Restoration, perhaps because the masters are employed in the war and few of them have the time necessary to write. A rare exception is de Saint-Martin, who published a treatise in 1800. It was after the Empire that the publication of manuals resumed.

Among these masters, we count Louis Justin Lafaugère, fencing master in the 25th regiment of chasseurs a cheval who published his “Treatise on the art of fencing” in 1820 [4], the Chevalier Châtelain, lieutenant-colonel of the cavalry in 1817 [5] as well as La Boëssière, son of the famous creator of the fencing mask in 1818 [6].

Espadon: what is it?

Probably one of the greatest mysteries of modern French fencing is that of the espadon. One only needs to open a dictionary published in the 19th century to quickly see how confusing the word itself is: an archaic name for the two-handed Renaissance sword, a popular word referring to a sword or broad-bladed sabre, a fish, and ultimately a term specific to fencers.

When the HEMA community first started to take an interest in the espadon, it was first understood as a type of weapon, like an epee de soldat or some sort of broadsword. This is due to the fact that French fencing uses a very confusing terminology to designate its styles, using the word “armes” to designate them. Armes can be translated as weapons or arms, so if one was saying that the espadon is an arme, it would make sense at first to consider it simply as an actual type of sword, and in some contexts it was.

As I wrote earlier, the word first starts to appear in the mid to late 16th century. It’s not entirely clear if it first shows up in French or Spanish texts, as it appears in dictionaries under both languages. It is also said to come from the Italian spadone, itself coming from the latin spadonem, but it seems more likely that the word made its way by Spain, where espadon means “very large sword”. Why the Spanish origin was ultimately forgot is quite intriguing.

What is somewhat clearer, is that it referred to a two-handed swords until the early 18th century. In his 1702 dictionnary, Furretière tells us that “A two handed sword or espadon, is a large sword which has a double grip held with two hands, and which is turned so fast and dexterously that one remains always covered”. In other sources, the definition is starting to change, defining it more loosely as a “battle sword with an edge and a point”.

At that point, it seems like the word got used rather readily to refer to any large bladed sword, either straight or curved, much like the English term “broadsword” in the same era. By the mid 18th century, it seems to have exited the formal language, and was then only found in the popular language, sometimes in the modified and much derided espadron, and staying there until the mid 19th century. [7] In most books that refer to both espadon and actual sabres or broadswords, you can sometimes notice a very telling habit. The author usually refers to espadon when talking about fencing, and uses “sabre” when he talks about the actual tangible weapon. For example, this is the case in de Saint-Martin. [8]

By the 19th century, dictionaries start to talk about espadon specifically as a style of fencing. Le Couturier, in his 1825 military dictionary, tells us that an espadon is an antiquated name for a two-handed sword but also a sort of exercise to learn how to wield the sabre and that it is a style preferred by soldiers. [9] It is also mentioned by Bardin in his thorough Dictionnaire de l’armée de terre who calls the art of the espadon, or to espadonner, a style of fencing using mostly cuts. Just like British broadsword, it is not a style that necessarily ignores the thrust completely, but is heavily focused on it. He also mentions how the term brought much confusion as its meaning evolved. [10]

Before you are tempted to open up a modern dictionary, know that the word is still present in the French language to designate a swordfish, and since the word has now lost all other meaning most Francophones today find the allusion to an espadon in fencing quite comical. The fish itself was named “espadon” because of it’s famous appendage, reminding people of a long sword, not the other way around. The name seems to appear first in the 1677 book Relation ou journal d’un voyage fait aux Indes Orientales by François L’Estra.

Returning to the concept of the “armes”, the word is used here figuratively to refer to a way of using these weapons rather than a specific type, concentrating on what the weapon can do rather than what it looks like. If you are still unsure about it, consider this: the pointe is also called an “arme” in fencing. Yet, there are no actual weapon called a “point” that is ever found in any manual, dictionary or otherwise. The closest being, “épée de pointe”, meaning a sword to do pointe with. “Arme” is a figure of speech.

Espadon is presented to us for the first time in the treatises of Martin in 1737 [11] and of Girard in 1740 [12]. The two masters indirectly describe the espadon to us not as a method to practice but one you might have to face, describing some techniques and how to overcome them with the pointe.

Some still resemble the Italian schools of the sixteenth century and others the military sabre styles of the following century. Juan Nicolas Perenat and de Saint-Martin are the only authors of manuals presenting a complete curriculum. [13]

De Saint-Martin was a pupil of the famous maître Danet. Little is known about this author other than what he left us in his textbook which covers pointe, espadon on foot and on horse, and boarding cutlass combat. He seems to allude to a certain military experience in his book. He published this manual from Vienna in 1804. Was he a French exile from the Revolution, or simply a fencing master who had found success in Austria? His name does indicate a possible link with the nobility. Either way, the espadon method presented by de Saint-Martin seems to be his creation, since by his own admission he never learned it from Danet. His method, however, is relatively similar to what was done elsewhere at the time and his espadon seems to be a fencing method that focuses on the cutting edge with little or no thrusting. One unique aspect of this author is his use of an engaging guard of quarte, a very peculiar choice that very few other masters makes. It is possible that he took this preference from his smallsword background.

It is established, thanks to certain sources such as Alexandre Müller, that the espadon is, after the Revolution, in decline. Müller dramatizes this state extremely, telling us that this school was wiped out, its students “mowed down” by the wars of the Revolution and the Empire [14]. Not necessarily because the style was ineffective, and caused its adherents to perish, but perhaps because it was mostly practiced in the military, and that so many of them perished in some of the most extensive and brutal series of campaigns in European history. Yet the style still seems to be taught during the Empire and even long afterward. We still find a few masters until the 1830s, but then seems to have completely disappeared in favor of its little sibling the contre-pointe.

The contre-pointe: between two worlds

At the junction of the espadon and the pointe is the contre-pointe. As with the espadon, the term is first encountered in a Spanish fencing treatise published by Juan (probably Jean) Nicolas Perenat, a French fencing master at the Cadiz Naval Academy in 1758 [15]. His method clearly breaks with the Spanish approach and rather reflects what is done in France, a vision that follows Spanish naval reforms of the time. He then presents us with a section on the sabre and on the contrapunta which seems to refer to the way of defeating a swordsman while one is armed with a sabre. Domenico Angelo gives us his own – and first – definition in 1763 in L’école des armes. He reveals to us that some espadonneurs mix their game with thrusts, which is called “doing the contre-pointe” [16].

The style is taught in France as evidenced by some advertisements published by fencing masters and the various contre-pointe diplomas. However, few authors publish on the subject, and one has to look abroad to learn more about the practice. Alexandre Valville was the first master to publish on this subject in 1817 in Saint Petersburg. He introduced in his treatise a few guards and espadon techniques, but focuses on the contre-pointe method. He is – to my knowledge – the only fencing author that really seems to refer to the contre-pointe as some sort of weapon, by saying it is worn by Russian officers. It is especially strange since, in his text, Valville never calls the weapon itself a “contre-pointe” but a “sabre”. Is he pushing the figure of speech so far as to say that the officers are now “carrying” this style of fencing or are armed with swords that can be used in this way? Or was this part of the text not his own work? Regardless, this choice of word has created a lot of confusion around the nature of the term.

The contre-pointe combines the elements of the pointe with techniques of espadon. As is the case with the pointe, fencers try to limit the movements of the arm as much as possible to ensure its coverage by the weapon. Thus, the cuts are mainly given by movements of the wrist to avoid revealing a forearm that could be intercepted by the opponent, or to create an opening towards the body that can be exploited by a pointeur. Tighter parries than espadon are also used, they use the lunge almost exclusively, keep their points forward, their stance erased, and cover themselves with their hilt. Could it be that this style was created in reaction to the rise of smallsword fencing? This would line up with what Augustin Grisier wrote in his scathing criticism of Valville in 1847:

The contre-pointe, of which you have quite wrongly neglected the definition, being,

I’ll remind you, the art of defending oneself against the point, it is necessary, in order to carry out the disarmament or to avoid death by a straight thrust, to move the sabre through the most direct line. [17]

The bayonet: the other pointe

The Napoleonic period also saw the birth of a whole new type of fencing, namely bayonet fencing. The fruit of the work of Joseph Pinette and his father, a Franco-Belgian master at arms serving in a company of infantry riflemen under the orders of General Junot. It was during the Egyptian campaign that they developed this method by facing Mamluk horsemen. Fighting in Spain, Portugal and even in Waterloo, Pinette taught his method to his comrades [18]. His fame was such, that at the end of the war his teaching was sought after by other fencers, notably the Prussian Von Selmnitz who published the first manual on bayonet fencing based on the teachings of Pinette [19]. This method came to be adopted by the French army several years later. To learn more about it, I invite you to read the excellent books on this topic by Julien Garry (referenced in the bibliography).

Alexandre Müller also published his own method on bayonet fencing based on his experience in the Grand Army. His method seems like a fairly classical approach to what was published later, but unfortunately it won’t enjoy the same popularity in France.

Cavalry fencing: another language

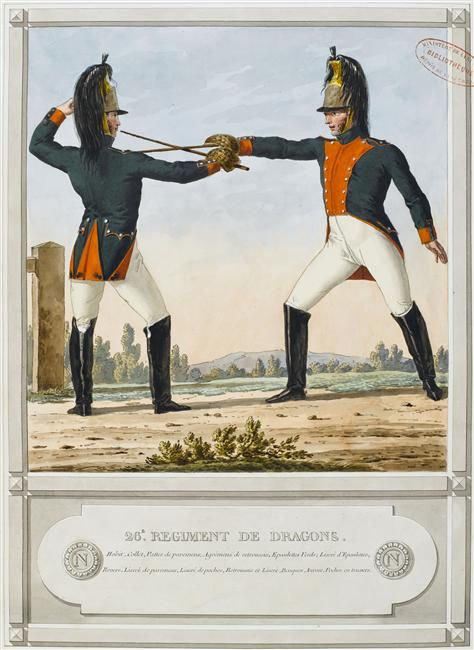

Weapons weren’t just practiced on foot, of course. Cavalry fencing had a certain heyday during the Empire period, but its teaching was once again rather optional.

The first manual published about it was that of Alexandre Müller, a native of Westphalia and a career officer in the Grande Armée [20]. He served during the Russian campaign where he was appointed captain. During the Restoration, he set about completing the writing of an imposing treatise on horse fencing in the light cavalry published in 1816 and which led him to teach at Saumur. This richly illustrated manual has remained a reference for several decades, being reissued many times.

Through this volume, Müller shows us the peculiarities of fencing on horseback, a type of fencing totally different from fencing on foot. As N.J. Didiez explains:

When we examine the question [the difference between fencing on foot and on horse] maturely, we will find, I think, that these relations are none other than those which we can conceive between two different languages; one can find here and there a few words having similar relations by a common etymology, but in general the constitutive form of the words, their value, the turns of sentences will be very different. [21]

Indeed, a common confusion around fencing on a horse is that it is to be applied, or at least can be adapted, to fencing on foot. While by the mid 19th century certain authors do try to create systems that can be used in both contexts with minimal alterations, Napoleonic era fencing draws a rather strong line between the two. Cavalry sabre generally uses much wider cuts and parries while fencing on foot tends to use much more minimalist movements, for the simple reason that a man on horse can afford to use such motions against an opponent that does not move as he would on foot, or one who is literally fighting on a different level. The presence of the horse changes the nature of the fighting very deeply.

The Müller method seems to be very representative of its time, for in 1827 the author sued General de Durfot for plagiarism. Although the latter served under the English flag, it seems that the two authors simply came at the same conclusions on several points and the lawsuit was therefore dismissed.

The fencing masters: a figure of controversy

But what is the place of the fencing master in the Grand Army? To fully understand the context of teaching fencing under Napoleon, we must once again look back in time. While it would be easy to see this fencing through a modern lens, we have to put aside Hollywood images of soldiers trained in sword handling under the command of a vociferous commanding officer. Indeed, in France, fencing was first and foremost an individual activity. The regimental masters or provosts gave private lessons to one or a handful of students at a time, most of the time for a fee. Unless the commanding officer decided to pay lessons to all his men, this training was at the discretion of the soldier. I would argue that this state of affairs was probably the norm across pre industrial armies for quite a long time, if not for most of history.

The position of fencing master allows the master to earn an additional salary in the first place by offering his lessons to officers and soldiers. A soldier’s pay was not always so great, and so many other sub businesses existed inside a regiment, such as the selling of food or drinks. The sword is by then carried of course by cavaliers, but also officers, sergeants, grenadiers, musicians, artillerymen, light infantrymen as well as by certain elite corps and… by fencing masters. Although the rifleman is now only equipped with his rifle and bayonet, he too is a potential client of the master at arms. Indeed, the use of fencing is not only found on the battlefield. Hand-to-hand combat has, since the 17th century and the popularization of firearms, become increasingly rare. It happens that bayonet fights take place, and that officers or soldiers have to defend their lives with their sabre or their sword, but beyond this consideration, no doubt important for some soldiers, what seems perhaps still to be more common is the duel.

In some soldiers memoirs we do find detailed accounts of duels. As mentioned above, even without their swords, which had been removed from their equipment in 1767, the fusiliers managed to settle their disputes with cold steel. The soldier and future general Jean Antoine Rossignol is thus twice forced to fight in a duel with the bayonet held not with the gun, but with the hand [22]. Rossignol being himself a provost, then later fencing master, he teaches us some interesting facts about the culture of regimental fencing.

Rossignol, unable to afford a fencing master, began his apprenticeship with a comrade in his regiment using baguettes, or wooden sticks used to teach espadon. After this four-month apprenticeship, Rossignol began to fight regularly in duels and also began to teach. He later took lessons at the Académie de Paris where he began teaching for three years, all the while continuing his service. This shows us a certain lack of boundaries between the world of civilian and military fencing which were not quite as different as one would expect.

Rossignol gives us some ideas of the organization of military fencing. The different companies within a regiment, such as chasseurs or grenadiers, each had their own dedicated masters, themselves represented by their First Fencing Master. Rossignol also tells us about the receptions and assaults given by masters and students when a master from another regiment was passing through. We can see how a whole culture is therefore developing around the teaching of fencing amongst the military, with its rituals and its hierarchy. Rossignol’s experience certainly dates back to the early days of the Revolution, before his participation in the storming of the Bastille, but we can believe that the learning of arms did not change fundamentally between that time and the end of the Empire.

You might think of the masters of the day as fairly well-regarded figures in society and of soldiers in general, yet there is some literature that suggests that their reputation was actually rather mixed. The master at arms is then strongly associated with the culture of dueling, which the French government has tried to suppress since the 16th century with little success. The French Republic had removed duelling as a criminal offense, and though there is a popular story going around that Napoleon had outlawed duelling, no such law can be found, outside of a temporary general order to the army stationed in Boulogne, enacted to repress a duelling craze which grew out of control among idle soldiers waiting to invade England, and which probably was misinterpreted by some as a law. There are also no indications that Napoleon himself disapproved of duelling. If anything, he seemed to have held the same feeling towards it as most French officers; that it was a necessary practice in the military.

Rossignol shows clearly in his many duels how the fencing masters were involved in the process. We also notice in some memoirs that the duel was an initiatory step for the soldier, and that it was therefore more tolerated in this environment than it would be in society in general. To prove his bravery to his comrades they manage to push him to fight, sometimes with the complicity of the master. One comes to suspect the fencing masters of fueling this culture of dueling for their own ends. This opinion is presented without any subtlety by Jean-Toussaint Merle and Maurice Ourry in their 1812 vaudeville “A day in the garrison”.

In this one-act play, possibly based on the military service performed by Merle, the recruit Moutonnet (Sheepy) is taken care of upon his arrival by the fencing master Bataille (Battle) who, realizing that he can make some money thanks to Moutonnet’s great credulity, teaches him the basics of espadon. The authors take the opportunity to poke fun at the confusing vocabulary of fencing when Bataille asks Moutonnet what he would like to learn:

Bataille: You have to know which weapon you choose first.

Moutonnet: Which weapon?

Bataille: Yes, if it’s the pointe or the espadon, the sword or the briquet (lighter).

Moutonnet: The briquet? ..

Bataille: Yes, the sabre. [23]

As soon as this short apprenticeship is over, Bataille tries to provoke a duel between Moutonnet and another soldier named Lavalleur (Swallower). Bataille goes so far as to comically dictate Moutonnet’s lines, manipulating him like a puppet. The duel is interrupted by the arrival of anonymous enemies, Moutonnet and Lavalleur forgetting their quarrel in a burst of patriotism to go together to face them. It’s hard not to see some promotion of national unity amid the disastrous Russian campaign and heralding unrest to come, as well as some denunciation of the duel in favor of a clash of nations.

vaudeville by Jean-Toussaint Merle and Maurice Ourry

Costumes of Cazot (Bataille) and Brunet (Moutonnet), Martinet (Paris), 1812

This piece fits perfectly with certain testimonies left by various soldiers, in particular the famous Captain Coignet. In his memoirs, Coignet also tells us about his apprenticeship in fencing with the masters of his regiment, the 96th of the line, who pushed him to four hours of exercise per day followed by two hours of fencing in the salle, and this for three whole months. Interestingly, this training regimen of six hours for several months seems to come back fairly often in historical accounts. Coignet very quickly finds himself in a duel which he describes to us as follows:

I became very strong in arms; I was flexible, I had two good fencing masters who pushed me. They had singled me out and they had felt my wallet; they were courting me. I paid them the drop (these two drunkards needed that). I had no reason to complain, for after two months they put a great strain on me; they made me look for a quarrel, even without a cause.

“Come on!” said this braggard to me, “Take your sabre! That I draw you a drop of blood!”

“Well! Come on, mister scoundrel.”

“Pick a witness.”

“I do not have any. “

And my old master, who was involved in the plot, said to me:

” Do you want me to be your witness?”

“I wouldn’t mind, father Palbrois.”

“On our way!” he said “No excuses! “And off we go, the four of us: we were not far in the Luxembourg Gardens, there were some old hovels there, and they were leading me between old walls. There, coats off, I put myself on guard. ” Well! Attack first.” I said.

“No.” he told me.

“Very well! On guard! “I rushed at him; I didn’t give him time to gather himself. Here is my master standing in the way, sword in hand. I pushed him away, saying:

“Get away, let me kill him!”

“Let’s go! It’s over, kiss! “And we went for a drink. I said:

“What about this drop of blood? Does he not want it anymore?” “

“It’s a joke.” my master told me.I was recognized as a good grenadier. I saw where they were going with it, it was a test to make me pay my share. [24]

This is probably the best description of the duel as a test of the young recruit. This institution was so entrenched that the military still tolerated dueling for most of the 19th century, even attempting to regulate it. After seriously injuring another soldier in a duel, Rossignol is threatened with imprisonment by his sergeant-major. Scared, Rossignol confesses and admits he didn’t want to look like a coward. This argument seems sufficient for the sergeant-major to release him on the spot, with a smile. [25]

During the wars of the Empire, many masters and provosts of fencing were taken prisoner by the enemy. We then find not only testimonies of training done on pontoons, but also masters’ certificates issued in prison camps such as Norman Cross or Dartmoor prisons in England. American prisonners at Dartmoor, such as Uriah Levy, first Jewish commodore of the US Navy, took the opportunity to learn fencing from some of them. [26]

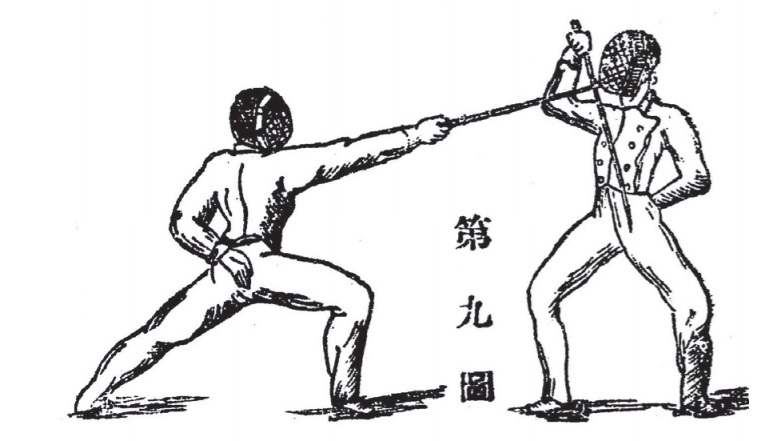

It would seem that these richly decorated diplomas began to appear during the Empire. The pattern appears to be fairly regular. The diploma usually depicts two fencers playing under the eye of military masters. The certificate lists the name and affiliation of the candidate, and invites the undersigned to provide assistance as needed. The large number of signatories to these diplomas, often thirty in number, shows us the very large population of military masters in the regiments. They denote the passage of a fencer to the title of provost or master, sometimes simply in “fencing”, which was sometimes used to describe pointe, but more often for more specific matters such as the pointe, the espadon or the contre-pointe but also on more specific weapons. such as the baton, the flail or the cane.

La Canne and Le Baton: A specialty of the sailor?

Indeed, even if the weapons described previously are really what most would associate with fencing, others were also practiced, especially, it seems, in the Imperial Navy. The sailor of the Imperial Guard Henri Ducor tells us how fencing was then part of the entertainment on board a Spanish prison ship on which he was imprisoned from 1808 to 1811, and in the prison camps of Russia from 1812 to 1814. At the end of the war, Ducor tells us that several soldiers opened “fencing salles, where all types of fencing were demonstrated, pointe, contre-pointe, espadon, baton, la canne, and flail. It was especially in these last three kinds of exercises that the sailors stood out [27] “.

I have already written quite a bit about la canne and le baton, so I will try not to repeat myself here, but it is not quite clear how these methods came to evolve, as we have very few sources. We do know that the practice was very popular in Brittany, which had an extant naval culture, so it is not impossible that the art of the bâton à deux bouts became a popular art among sailors through the contribution of these Breton sailors bringing their favorite pastime on board.

Even though sailors were apparently recognized for their skills with blunt instruments, swordsmanship also seemed to have been a fairly popular activity, according to the memoirs of then Lt. François Leconte who tells us that most sailors would be proficient in fencing with sabre and foil, taking instruction from naval artillerymen who, according to him, composed most of the fencing masters in the French Navy. They would also routinely train in dancing, and adopt a peculiar way of walking from these activities, with their feet turned at an extreme outward angle as a result. He also mentions how many would also wear a sharpened foil next to their cutlass. Their presence at the military barracks in Vincennes, as they were called to help defend the city during the campaign of France, contributed to many sabre fights with the horse artillerymen with whom they shared those barracks. [28]

Norman Cross War Prison, England, ca. 1797. A close up shows several figures practicing fencing, as well as two practicing what looks like le baton. Interestingly, they are located in the sailors prison, in the lower right square as indicated in the no.10 in the legend. Of course, this is not a photograph, but the choice of putting them only in the sailor’s quarter perhaps points again to an association between the Navy and le baton.

Several sailors and soldiers therefore began to teach weapons at the end of their service. Certain masters like Grisier disliked these ex military fencing masters trained on prison ships which he called “demi-espadon wearers” as they were allowed to wear the military officer spadroon. Among them, there is of course Lafaugère, but also Pons l´Aîné, Larribeau survivor of Trafalgar and Medusa [29], or Michel. In addition to these illustrious characters, we can also imagine several hundred masters with a more humble background, such as this spurrier from the region of Le Mans in 1816:

Lonchamps, spurrier, makes all kinds of bridles and spurs. He also teaches the arms, contre-pointe and espadon, with principle and precision. His lessons start at 6 a.m. until nine, and from 5 until 8 p.m. His home is rue Dorée n.22. [30]

Fencing as a national export

The Napoleonic wars did not only contribute to the development of fencing in France. As in other fields, the Empire extended French influence in Europe and even beyond. Thus, we can identify several French masters teaching fencing abroad. We have already named de Saint-Martin, teacher at the Austrian court, Valville [31], general instructor in the Russian imperial guard, and who left a very marked mark on the fencing of this country until the end of the 19th century, Domenico Angelo and his son Henry, were both taught (at least in part for Henry) in France, as well as Francalanza teaching contre-pointe at the Military College of High Wycombe, the institution created by none other than Gaspard Le Marchant. To which extant he had an influence in the development of Le Marchant’s method is difficult to say.

It’s necessary to explain here that few armies in Europe had so many fencing masters in their ranks, or even in the civilian population. This was observed by Major Charles James in his Military Dictionnary of 1802, where he remarks that the British Military should imitate the French, in some limited capacity, by placing fencing masters in all of it’s Grenadier battalions. [32] I believe this is perhaps why we see so few books on French martial arts in France itself, and a need to rely on many exiled masters to learn more about them, as the demand for books was quite small when the availability of instructors (whose lessons could be cheaper than a book) was so great.

Some foreign soldiers of the Grande Armée, back in their country of origin, also contributed to the spread of French fencing. Among them is Christmann, a veteran of the Imperial Guard and native of Mainz whose method was exported not only to Germany but also to Greece [33]. Or Bertolini, who publishes a volume on the contre-pointe in Trieste [34]. Even in America, where some exiled soldiers such as FP Girard taught in Boston and Montreal [35], or even at the prestigious military academy of West Point in the United States where the first fencing master, Pierre Thomas, taught espadon, pointe and contre-pointe [36]. Napoleonic influence also continued to be felt in countries such as Italy where French military academies had been established.

A second wind, and a Second Empire

Following the Restoration, fencing spread but did not experience any major revival in the army. This is set to change with the coming to power of Napoleon III. The announcement of the Second Empire triggered a series of reforms that would give new impetus to military fencing. They began in 1851 by presenting the first offical regulation system teaching the use of the cutlass to sailors, which was followed by the creation of the gymnastics and fencing school of Joinville in 1852. The purpose of this school was to train soldiers to standardize the practice of physical activities. Joinville became a veritable factory for weapons masters, who were once again exported across the globe. It also created a new craze for fencing that slowly lead to the sport we know today.

The method took root in Japan, where a French mission was sent in 1866 to help train a new Japanese army. The mission was cut short, and did not return to the country until 1872, but French fencing was firmly established in the 1880s with the publication of the Japanese translation of the Joinville manual in 1889. This method left its traces in techniques later implemented by the Toyama school such as jukendo or Toyama Ryu [37].

In conclusion

Although we may be surprised at the longevity of the sword in an army based on the power of gunpowder like that of Napoleon, we must admit that its practice remained important, as can be seen by the thousands of sabres and swords resting in museum reserves or on private walls, as well as the literary and gestural heritage that the fencing masters of the Grand Army left us. The practice and study of historical martial arts helps us better understand this heritage today.

Bibliography

[1] Daressy, H. , Archives des maîtres darmes de Paris. Paris: Quantin, (1888), p.46.

[2] Chouinard, M. (15 octobre 2015), « Chasseurs et gentlemen : Histoire des arts martiaux au Québec », rapporté dans hemamisfits.com : https://hemamisfits.com/2015/10/19/chasseurs-et-gentlemen-histoire-des-arts-martiaux-au-quebec/ (9 mai 2020).

[3] Ravaton, H., Chirurgie d’armée ou traité des plaies d’armes à feu et d’armes blanches… Paris: Didot Lejeune (1768).

[4] Lafaugère, Louis Justin, Traité de l’art de faire des armes. Paris: Garnier (1825).

[5] Chatelain, René-Julien, Traité d’escrime à pied et à cheval. Paris: Magimel, Anselin et Pochard (1817).

[6] LaBoëssière de, Traité de l’art des armes, à l’usage des professeurs et des amateurs. Paris: Didot (1818).

[7] Molard, É, Dictionnaire du Mauvais Langage (1797).

[8] De Saint Martin, L’Art de faire des Armes reduit a ses vrais principes (1804).

[9] Le Couturier, François Gervais Edouard. Dictionnaire portatif et raisonné des connaissances militaires. France, n.p, (1825).

[10] Bardin, Étienne-Alexandre, Dictionnaire de l’armée de terre, ou Recherches historiques sur l’art et les usages militaires des anciens et des modernes. Partie 7, France (1841), p.2171.

[11] Martin, Le Maistre d’armes, ou l’Abrégé de l’exercice de l’épée démontrée par le sieur Martin. Strasbourg: L’auteur (1737).

[12] Girard Pierre-Jacques-François, Nouveau traité de la perfection sur le fait des armes … par le Sr P.-J.-F. Girard .. Paris: Moette (1736).

[13] de, S. M. J., L’art de faire des armes réduit a ses vrais principes: contenant tous les principes nécessaires à cet art, qui y sont expliqués d’une manière claire et intelligible … on y a joint un Traité de l’espadon, où on trouve les vrais principes de cet art … Vienne: Impr. J. Schrämble (1804).

[14] Müller Alexandre, Théorie sur l’escrime à cheval, pour se défendre aux avantages contre toute espèce d’armes blanches: Ornée de 51 planches en taille douce. Paris: Cordier. (1816), p. 1.

[15] Perinat Juan Nicolás, Arte de esgrimir florete y sable: por los principios más seguros, fáciles e inteligibles. En Cadiz: en la Imprenta de la Real Academia de Cavalleros Guardias-Marinas (1758).

[16] Angelo, D., L’école des armes, avec l’explication générale des principales attitudes et positions concernant l’escrime. Londres: R. & J. Dodsley (1763).

[17] Garry, J., La baïonnette: histoire d’une escrime de guerre. Paris: L’oeil d’or (2016).

[18] Perinat, Ibid.

[19] Selmnitz, E. von. (n.d.). Die Bajonetfechtkunst oder Lehre des Verhaltens mit dem Infanterie-Gewehre als Angriffs- und Vertheidigungs-Waffe.

[20] Müller, Alexandre. (n.d.). Rapporté de https://labibliothequemondialeducheval.org/bmc/personnesCheval/doc/pddn_p.BMC_2543.xml.

[21] Directeur du spectateur, Le Spectateur militaire, Recueil de science, d’art et d’histoire militaires : Volume 17 (1834), p. 463.

[22] Barrucand, Victor, La Vie Véritable Du Citoyen Jean Rossignol. Paris: E. Plon (1896), p. 15

[23] Merle, J. T., & Ourry, Une Journée de Garnison, comédie en un acte, mêlée de couplets, etc. Paris. (1812), p.25

[24]Coignet, J. R. , Mémoires d’un officier de l’empire: les cahiers du capitaine Coignet. Paris: Deux-Trois. (1850), P.79

[25] Barrucand, Victor., op. cit., p. 17

[26] Appel, Phyllis, Uriah Levy: From Cabin Boy to Commodore. N.p.: Graystone Enterprises LLC, (2016), p.12.

[27] Ducor, H., Aventures d’un marin de la garde impériale prisonnier de guerre sur les pontons espagnols, dans l’île de Cabréra, et en Russie ; pour faire suite a « L’histoire de la campagne de 1812 ». Paris: Dupont, p.. 137

[28] Leconte, François, Mémoires pittoresques d’un officier de marine, Brest, Le Pontois, (1851), p. 72

[29] Though certain documents make us doubt of his presence at Trafalgar.

[30] Département de la Sarthe, Affiches, annonces judiciaires, avis divers du Mans. Le Mans (1816), p.367

[31] Valville, A., Traité sur la contrepointe. Saint-Pétersbourg: Charles Kray (1817).

[32] James, Charles, An Universal Military Dictionary, T. Egerton, (1816), p. 889

[33] Müller, P., Theoretical and Applied Introduction to Swordsmanship (1847).

[34] Bertolini di Trento, B., Teorie sulla sciabola per una scuola di contropunta di genere misto. Ferrara (1856).

[35] Chouinard, M. (15 octobre 2015), « Chasseurs et gentlemen : Histoire des arts martiaux au Québec », rapporté dans hemamisfits.com : https://hemamisfits.com/2015/10/19/chasseurs-et-gentlemen-histoire-des-arts-martiaux-au-quebec/ (9 mai 2020)

[36] Cohen, R., By the sword: a history of gladiators, musketeers, duelists, Samurai, swashbucklers and points of honour. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan (2002), p. 258

[37] Tavernier, Baptiste. Forsaken Kendo . Kendo World Magazine, 7 (2014).

1 Comment