by Maxime Chouinard

There are very few fencing manuals that have a Canadian link. The first Canadian to write on the subject is probably Lt. William Pringle Green , who wrote an unpublished manuscript on naval swordsmanship and boarding maneuvers. Another is Clive Philipps Wooley, a figure of British Columbia’s history, who also authored the singlestick part of Allanson-Winn’s book Broadsword and singlestick in 1890.

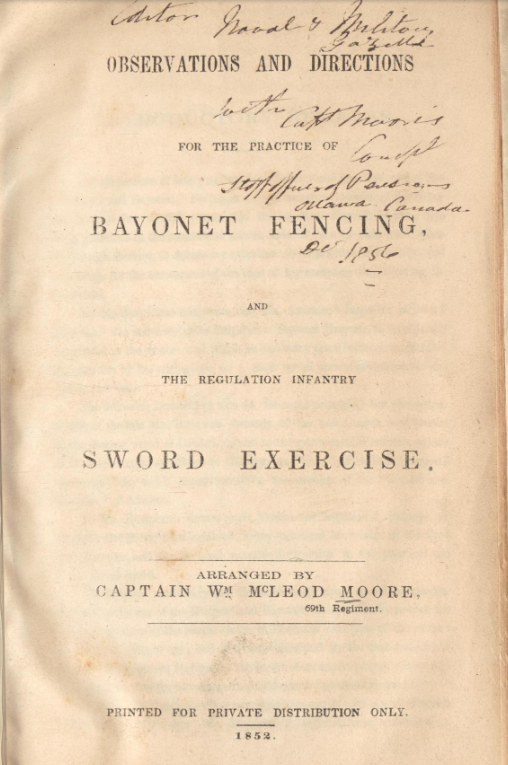

I was then quite pleasantly surprised to find the manual titled Observations and Directions for the Practice of Bayonet Fencing, and the Regulation Infantry Sword Exercise, while doing a research on a totally different subject. A volume which was published in the mid 19th century by a man living in Canada, in the same city I now teach fencing.

Rest assured, it is not one of the myriad of plagiarized copies of more famous manuals, nor is it a bland booklet on the basics of swordsmanship. This was actually an attempt at proposing a new method for the British military. And more importantly, this manual sheds light on another very influential, but unfortunately little known figure of British sabre fencing. Well look at the history of this manual, as well as how it fits in the lineage of Sgt. Joseph Bushman.

The author

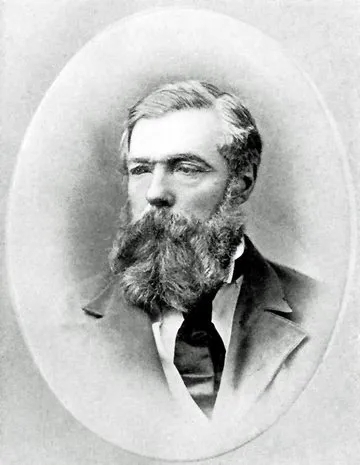

Lt. Col. William McLeod Moore was born in Kildare, Ireland, in 1810. The descendant of a long line of military officers, and the son of the only daughter of Scottish chieftain Norman John MacLeod of MacLeod and Dunvegan Castle. He studied at Aberdeen, and graduated from Sandhurst in 1831. He joined the 69th Regiment of Foot, where he served for more than 20 years, being stationed in Ireland, the Caribbean, Halifax, Malta, and Barbados.

In 1852, he was appointed staff officer of Out-Pensioners for the cities of Bytown and Kingston, Canada, and resided in Ottawa until his retirement in 1857, when Lord Elgin gave him command of the whole of Ottawa’s volunteer regiments. A few years later he moved to Laprairie, and finally Prescott, where he spent the remainder of his life until 1890.

The same year he moved to Canada, he published his Observations and Directions for the Practice of Bayonet Fencing, and the Regulation Infantry Sword Exercise. The book appears to have been self published in very low numbers, which probably explains how it completely evaded the attention of researchers so far. The copy that Google made available is held at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium, and is the only one have found as of date.

This copy of the book was signed by the author, and apparently sent to the Navy and Military Gazette in 1856, probably for review. A biography of McLeod states that the Gazette favorably reviewed his manual, though I have not found this article yet. It appears that the manual was published in the UK, judging by Moore’s signature in his introduction, but it seems that he was mostly promoting it from Ottawa.

Moore was described as a skilled swordsman, and “proficient in all athletic exercises” (The Freemason and Masonic Illustrated, Dec 17 1870). He mentions being a pupil of Angelo, and a long time practitioner of his method, though, as we will see later, Angelo was not the main influence for his manual.

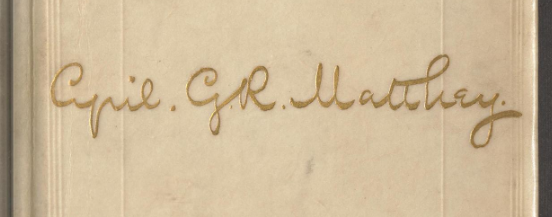

The (former) owner

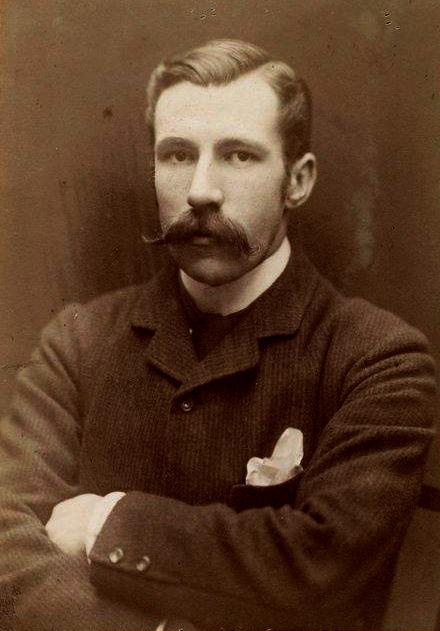

Cyril G.R. Matthey is noted as an ex libris on this copy, and even had his signed name printed on the front cover. It seems he had this done to several of the books in his collection, as others with similar covers can be found. The name may sound familiar to some, as Matthey is the person who found the manuscript of Paradoxes of Defense by George Silver at the British museum, and had it reprinted in 1891. Cyril G.R. Matthey was born in 1864, and was Colonel of the London Rifle Brigade, a member of the London Fencing Club, and honorific member of the Cercle d’Escrime de Bruxelles.

He is probably one of the least known figures of the Victorian HEMA movement of the late 19th century, unlike his close friends Hutton and Castle, but was nevertheless quite influential in the development of fencing in Britain, championing for a different kind of fencing to be taught to the military, and the usefulness of the practice to soldiers and officers. He was close to Hutton, and was apparently one of his executors.

The manual

Moore indicates that the two systems he is proposing were developed by Sgt. Joseph Bushman, formerly of the 2nd Regiment of Dragoon Guards. Moore was instructed in Bushman’s method through a student, Lt. John Colpoys from the 44th regiment of foot. Colpoys joined the 44th in 1847 as an ensign and adjudant. Like his teacher, he was very active in instructing and demonstrating broadsword fencing. He passed away in august 1852, mere days after receiving the rank of lieutenant. There is little doubt that Moore studied with Colpoys while both their regiments were stationed in Malta, between 1847 and 1851.

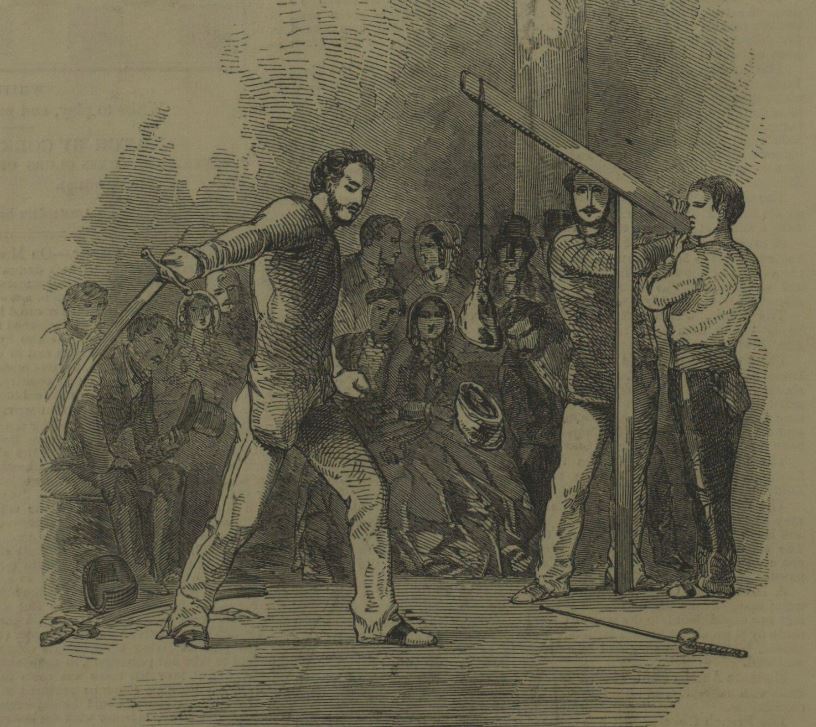

Bushman is unknown today, but was quite the star of British sabre fencing in the 1830s and 40s. He was a student of Henry Angelo the younger, and rose to become his assistant instructor, being showcased in public demonstrations given by the Angelo school.

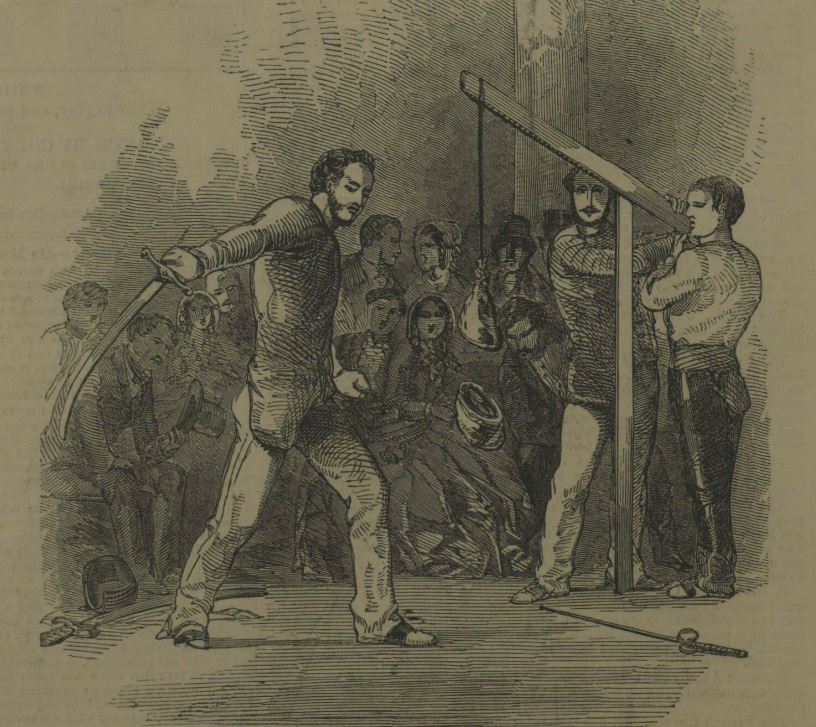

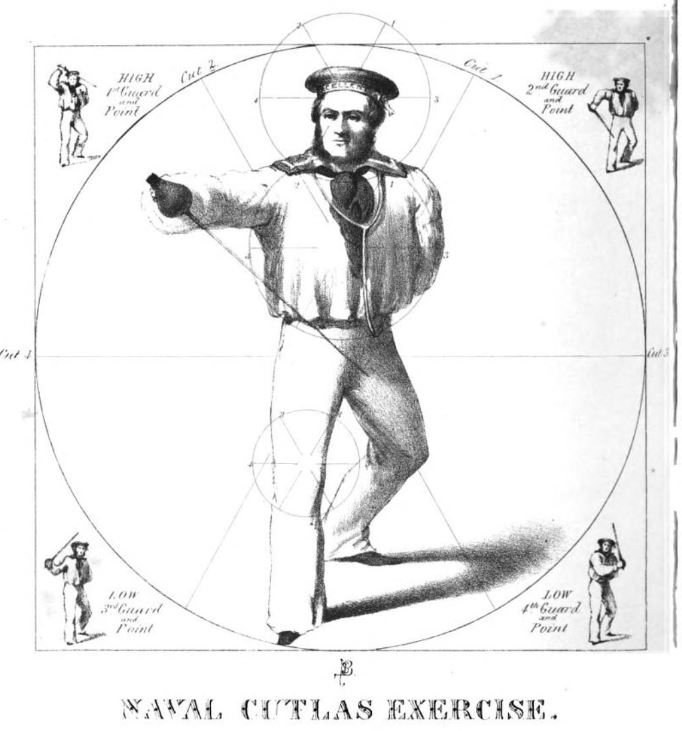

He appears to be either the originator- or at least the main proponent- of cutting feats, which were demonstrations and exercises in which a fencer would cut a variety of materials, such as bars of lead, mutton legs (this feat even became called “Bushman’s feat”) or silk scarves (“Saladin’s feat”). In these feats, he would use a large 1845 type naval cutlass, which served as the model for lead cutters, and even used a custom sword made by Wilkinson for Lord Hardinge.

Based on the illustration, I believe that the sword used was probably identical to the four Hardinge sabres that are now kept at the Royal Armouries in Leeds, if it is not actually one of those. They were all made by Wilkinson in 1847.

Bushman died at the peak of his popularity, in 1849, stroke down by the cholera epidemic which was sweeping through Britain. His demonstrations captivated public attention so much that this is almost all of what his necrology mentioned.

Although his name became lost through time, his legacy endured through his students, such as Sgt. William Tuohy, who successfully proposed a replacement to Angelo’s broadsword method in 1857. While Musgrave Waite, author of Lessons in sabre in 1880, not a direct student of Bushman, was part of his lineage through his own teacher.

The Bushman method of swordplay

Although Bushman’s system is still evidently a product of the Angelo school, there are a few points which make it easy to differentiate.

1-The guards

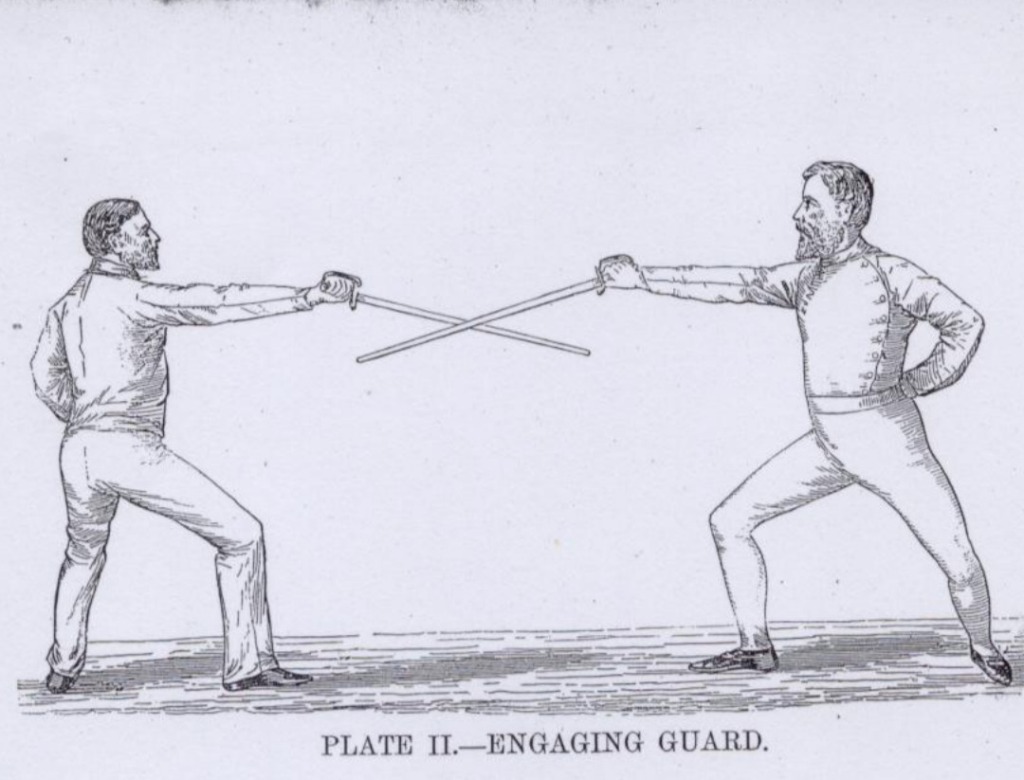

First is the engaging guard. While Angelo mainly teaches a high hanging guard as a starting position, all of Bushman’s pupils rather choose to go for the high seconde guard, where the guard lines up with the lead shoulder instead of hovering over the head.

It also removes the leg slipping on every parry, which was criticized by many authors, including Moore who calls it “theatrical style”, along with the Point and Parry practice. He notes that it needlessly slows down ripostes. Interestingly, this hallmark of Angelo’s method is – along with the hanging guard as engagement- probably the least followed when fencing today, and for the same reasons outlined by these authors.

All of these authors remove certain guards from Angelo, to only keep four of them; usually prime, seconde, tierce and quarte. The half circle and low hanger are discarded and criticized being of little use in actual fencing. Tierce and quarte are used to cover much of the inside and outside lines, in their high or low versions.

2- Cuts

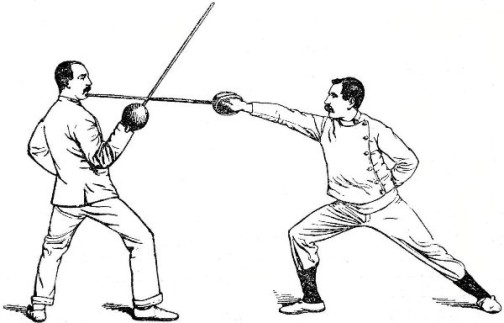

Another difference is the removal of cut seven, the vertical cut to the head. Waite is probably the only one that mentions it as an option, but is very critical of its actual usefulness on the battlefield, citing the difficulty of cutting through an opponent’s helmet, echoing here the opinions of John Gaspard Le Marchant or Roworth a century earlier. Tuohy goes even further, and removes upward cuts three and four. He is certainly an outlier in this regard though. Moore argues that this vertical cut is the only one that cannot be given directly from an engaging guard, and necessitates drawing back the hand in preparation, in a “battle axe style” above the head, the blade hanging down in a line with the back. He argues that this makes it very easy for an opponent to land a stop thrust, and can cause one to lose their swords or be left wide open if missing their cut entirely.

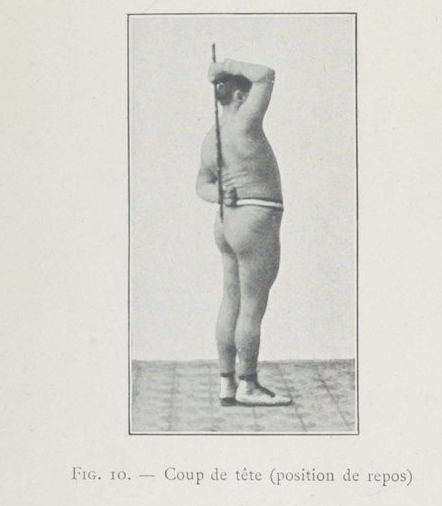

This is a rather interesting point. The Angelos method is rather confusing when describing the seven cuts, since it often blurs the line between fencing on foot and on horse. Moore’s description of cut seven is the same here as the one Angelo uses, and incidentally is the same method you would see used in the French La Canne of Leboucher or Charlemont when delivering a downward blow to the head. Moore is explicit here: “there being no other position by which the vertical cut could be delivered”; except for a variation resting the sword on the right shoulder instead, reminding one of the way it is given in Radaellian sabre, with a full arm motion.

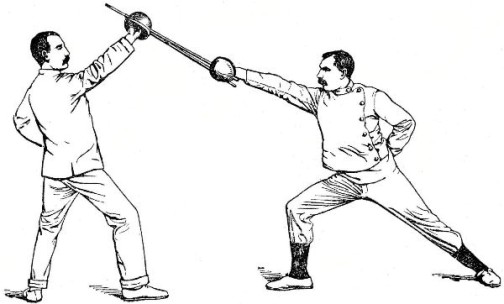

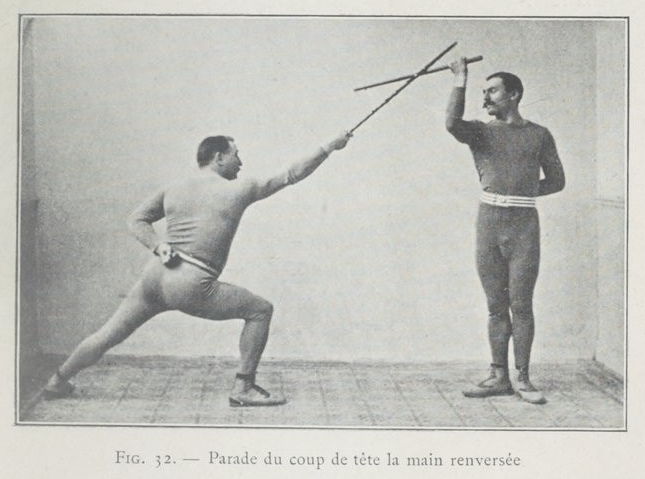

Charles Charlemont, in his father’s manual on boxing and La canne, showing here the development of a head strike. The preparation seem very similar to what is described in Angelo and Moore.

This raises an interesting question: is the common interpretation of the seventh cut in the Angelo tradition wrong? I must say I cannot remember ever seeing anyone practice it as such, and instead doing it mostly as a direct draw cut, or at most with a full wrist moulinet, as is often described in French sources for example. Yet, looking at the Angelo corpus, including those who copied him, the instruction is clear: bring the hilt above the head, the point downward and the blade along the back, and cut down to the middle. All other cuts on foot are described as done from the wrist but this one.

3- Cutting feats

Another point in common for all the sources linked to Bushman is the inclusion of cutting feats as mandatory exercises for students, and the insistence on making “effective cuts”. Once again, Tuohy goes to an extreme, teaching larger cuts than is usually seen in sabre fencing, possibly as a way to quickly teach recruits, especially sailors, before introducing smaller motions.

4- Bayonet

Finally, the manuals all include bayonet. Henry Angelo the younger had devised his own bayonet method, which we mostly see in a publication done after his passing. Here, all the sources differ somewhat form each other. Moore is somewhere in between Angelo and Tuohy. He uses a similar engaging guard as Angelo, with the characteristic “chest drawn in” position, while Tuohy uses a straight back position. Waite is similar to Tuohy in this regard, but his manual touches very briefly on the bayonet, mostly as a weapon for the sabreur to be defended against. All methods use the same four parries.

Where Moore is closer to Tuohy is in the way he introduces two engaging guards: engage left, and engage right, which are both the same, but with a different leading foot and shoulder. Angelo presents only one engaging guard.

Bushman’s influence on British fencing

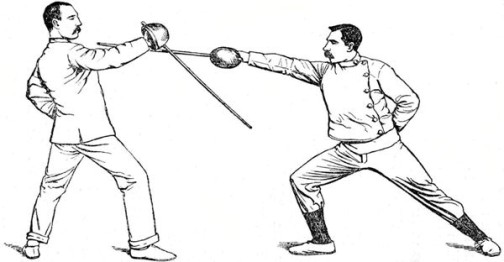

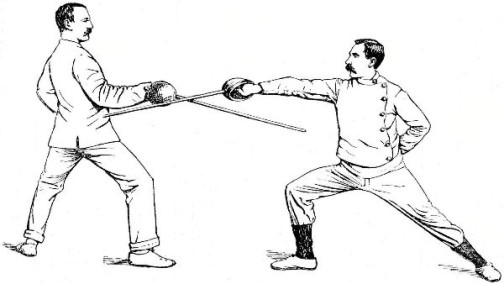

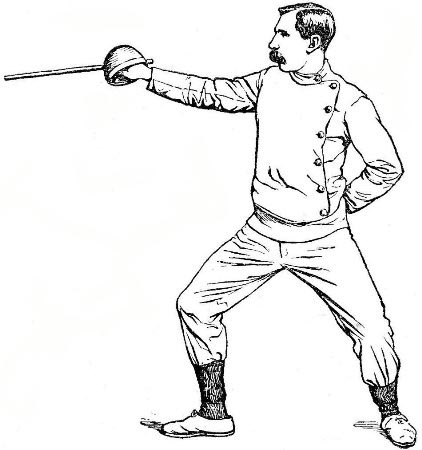

Based on these points, we can start to identify followers of Bushman in other sources, such as the singlestick part of Broadsword and Quarterstaff. While the book was mostly the work of Allanson-Winn, most people ignore that it is Clive Phillips-Wolley, another Canadian immigrant whom I mentioned in the introduction, who authored the part on the fencing stick. When looking at the photo above, it is obvious that Wolley served as a model for the illustrations in his chapter.

The method shown by Wolley is clearly that of Bushman, but interestingly is not that of Tuohy, suggesting that Wolley possibly trained with of of Bushman’s students. You can of course recognize the high seconde guard, six cutting angles with a lack of a straight head cut, and only four parries. Meanwhile, Allanson-Winn draws a little more from Angelo in his chapter on the sabre/broadsword.

After all these years, it always feels great to see that there is still more material to be uncovered from an era so rich in fencing and martial arts publications, and that we can still develop our understanding of their practical applications.

As a final note, I will leave you on the is passage of Moore’s manual, which, as an Irish stick teacher, really made my day, and which I could not avoid sharing.

“The skill our cavalry obtained in the last European war was from the practice of the “Loose stick play” ; The necessity of which was taught them by the fact that the best sword drills of a cavalry regiment were completely worsted by some Irish peasants with the stick.”

Capt. William McLeod Moore · 1852