If you have a certain interest in 19th century martial arts, you probably read about the Joinville staff tradition from France. Part of the other military great stick traditions of Europe, the French baton has a very long documented history from at least the 13th century, and while it disappeared in its original form it is somewhat kept alive through the Bâton Fédéral of the French Canne de Combat Federation; which is currently restoring it to its former glory. So today we will explore the history of this weapon which spread all over the globe, and how to approach it.

Playing with sticks: The Joueurs de baston of Medieval France

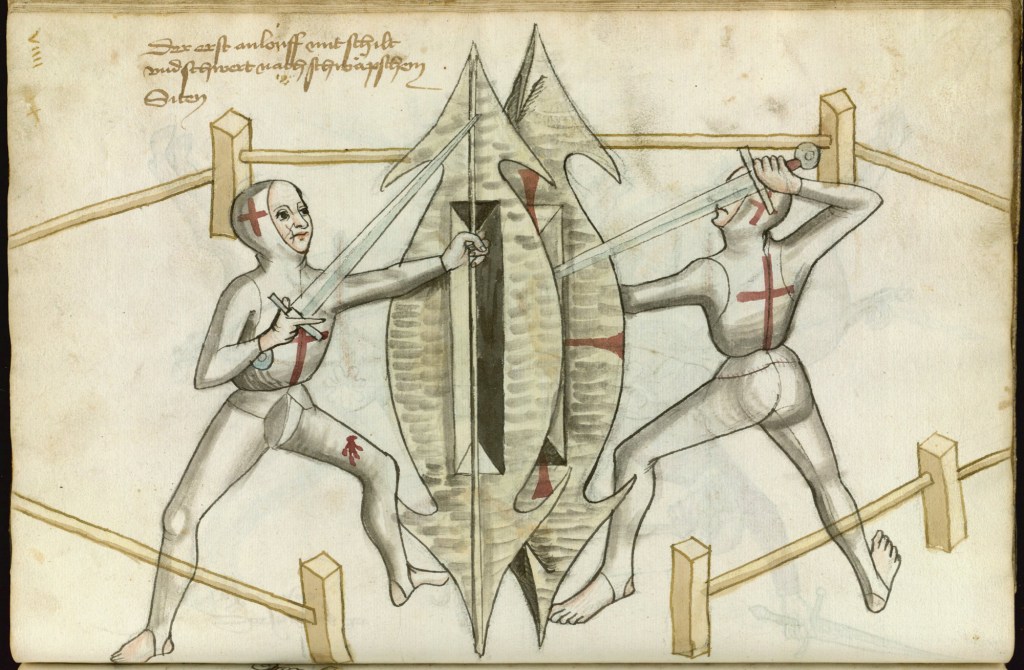

The origins of the French Baton are unclear like most vernacular martial arts, but one of the first mentions of the Baton in France can be found when in 1205 Phillip II ruled that the bâton d’armes (arming staff) was to be three feet long. [1]This weapon was meant to be used in judicial duels between commoners, often paired with the use of the Harasse (judicial shield); exemplifying the image of the stick as a symbol of social rank.

Harasse shields used here in Talhoffer’s 1459 treatise. In France, the swords would have been replaced by three feet long sticks for commoners

In the 16th century, we find the first mention of the bâton à deux bouts or two ended staff. This type of staff was equipped with iron bands, or spikes, at each end and seems to have been a continuation of the bâton d’armes. Not only was this weapon popular among the common classes of France, there were masters and even schools specialized in teaching its use, and this is how we first learn of its existence through the rules of the “masters of the game of the two ended staff” (maîtres du jeu du baton à deux bouts) Jean du Prate of Beaumes and Bertrand Borion of Mazan in 1501. Du Prate was also a master of the sword while Borion was simply a master of the staves; implying that both necessitated separate certifications. The minute book of Jean Forge mentions the rules of instruction in this art.[2]

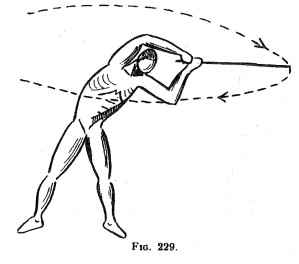

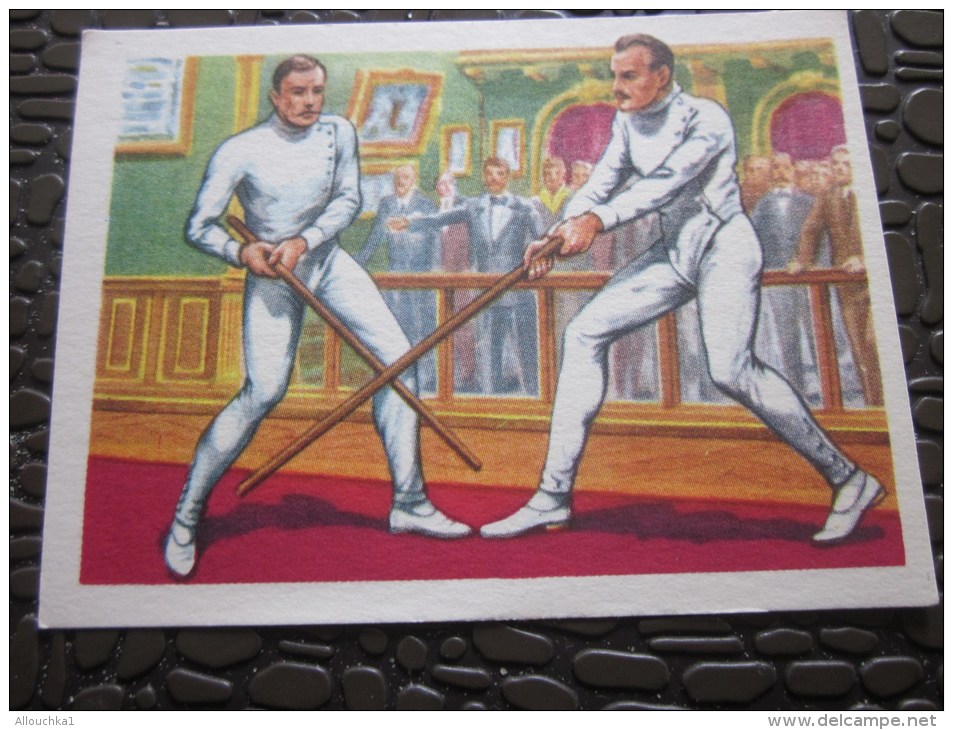

Paulus Hector Mair’s “Peasant Stick” (ca 1540) is interestingly one of the earliest methods to ressemble baton, especially the Joinville method, with its circular blows and parries done always hands up.

The student first had to make a pledge on two crossed staves. Following the pledge the master gave his first lesson; at which time the student had to pay half of the fee, the other paid at the end of the month. For a month, the master would only teach the parries until the student was ready to “pass his defense”, where he would demonstrate his ability in parrying every blow the master would throw at him. Afterward he was allowed to attack. At the end of his apprenticeship, he would be received as Journeyman. A more detailed account of these rules shall be the subject of a future article.

The fencing masters’ adoption

In 1567 the staff is mentioned in the statutes of the masters players and fencers of the sword; the first nationally recognized statutes for French fencing masters, which had been previously legislated by municipalities or parliaments. In 1664, the Bâton à deux bouts is still part of the Fencing masters curriculum, but at this point a significant change is introduced in the description of the test. A person wishing to become a master now has to demonstrate his ability with the Bâton à deux bouts, the halberd, and the espadon. Contrary to the rapier or smallsword, the test no longer mentions bouting. It seems that these weapons would continue to be part of the corporation’s requirements until the French Revolution.

The aim was partly to produce well-rounded fencers, but also to block the way of foreign fencing masters; mostly Italians. Indeed most Italian masters at this point no longer practiced the staff, halberd and two handed sword but in order to teach in France you needed to demonstrate your ability with these; unless you could get a royal exemption (which were very often repealed).[3]

While the description of the Bâton à deux bouts varies, it seems that in most cases it would be equipped with spikes on each end, or, at least, iron ferrules. George Silver shows a comparable staff in his “Paradoxes of defense” but the only manual we have which truly describes the French method is contained in Johann Georg Paschen’s volumes most especially his 1660 Kurtze Anleitung wie der Baston à deux bous, Jägerstock, oder halbe Pique oder Springestock wie ihn etliche nennen, also translated into French. Pasha makes it clear that this exercise is well known in France, but rarely seen in Germany, and makes the habitual remark that such a weapon is most suited to fight multiple opponents; even armed with swords. While his method bears some differences to what will be seen in the military style of the 19th century, one can already see some of its trademarks including the large moulinets and four face exercises.

Paschen’s Baston à deux bous

One famous example of a Baton player was the Chevalier de St-Georges, who learned the use of the Baton from his instructor Boëssière in 1752. [4] Very few documented instances of its use seem to have been recorded in the 18th century as the sword dominated the interest of most authors; it literally took a revolution to put the focus on other subjects. It is indeed after the French Revolution that we will truly start to read about the use of the French Baton in three different ways: the military schools, civilian masters and through the workers’ guilds or Compagnons.

Military matters: birth of the Joinville method

Already in 1811, an NCO of the 12th Light named Montret was mentioned as the author of a bayonet manual but which contained “more exercises for the Baton than the bayonet”.[5] Unfortunately it seems that this manuscript was never published.

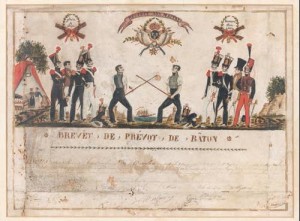

One of the earliest military certificate on Baton here recognising a Prevost from Bordeaux in 1817

After the Napoleonic Wars, the Baton was exported to various armies by French fencing masters and veterans of the Grande Armée. In 1817, Alexandre Valville- then instructor at the Imperial Lyceum and master of the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin- published two volumes on fencing; a work which took him 22 years to complete.[6] It is not clear at the moment if it contains Baton as the volumes are scarce, but it is clear that Valville had a lasting impression on Russian military fencing. A year after his publication he was be named General Fencing Master of the Guard, a position he occupied until 1840, before retiring and going back to France. His method of saber fencing seems to have survived in the Imperial Guard at least until 1895.

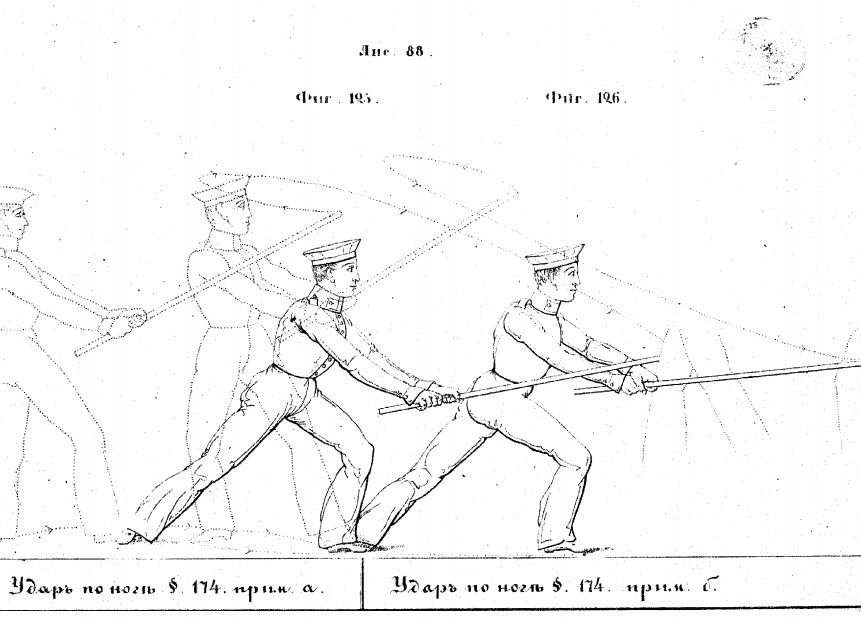

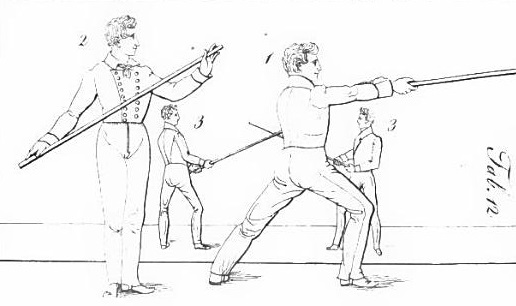

A peculiar illustration from Valville’s manual, perhaps inspired by Baton

The following fencing master of the Guard, named Sokolov, also published a manual in 1843 with a fencing style very similar to Valville, and with a detailed Baton method. It is quite possible that this section came directly from Valville’s teachings.

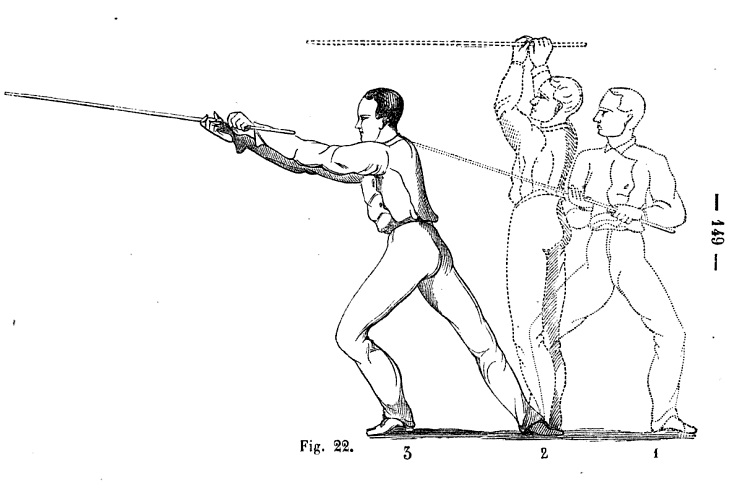

Part of Sokolov’s 1843 manual

A further indication of a connection is found in F.C. Christmann’s manual of 1838. Although born in Mainz, Christmann was a member of Napoleon’s Guard and said in his manual that the French began learning the Baton at a young age, and continue to do so in the army and that Germans should imitate them. The saber method he shows is similar to Valville, and the Baton is quite close to Sokolov and even to later Joinville material. That these methods show such crisp resemblances, even though they are removed both geographically and chronologically from Napoleon’s time, seem to indicate that this would have been a standard practice in the Grande Armée.

Christmann’s 1838 manual

An interpretation of Christmann’s Baton

In 1850, the French military started to elaborate the idea of organizing a gymnastic school which was intended to standardize the methods being taught in all physical arts, including fencing. Indeed at this time, the officers were complaining that every fencing master was teaching his own style and that no unified methodology could be agreed on. In 1852, the École Normale Militaire de Gymnastique de Joinville opened its doors under the direction of Commander Louis d’Argy, assisted by Napoléon Laisné. Its role was to train sports instructors for the French military.

Laisné was a student of Pestalozzi and Amoros, the latter being considered the father of French gymnastics, and was himself the director of the gymnasiums of Paris, the gymnastics professor of the Polytechnique, and created a type of “medical gymnastic” program for the patients of Paris’ hospitals. In his 1850 manual on practical gymnastic, Laisné puts the Baton in the first rank of gymnastic exercises, as producing excellent results on health and bearing.

Laisné’s Baton

The French military being considered a reference all throughout the 19th century, the French Joinville method was exported (although not always officially adopted in its entirety) elsewhere such as in Belgium, Spain, United-States, Greece, Canada, Germany, Russia, and Japan as well as in the various French colonies of the time.

Often erroneously thought to be based on 16th century Italian swordplay, Alfred Hutton’s “Great Stick” is more or less a copy of the Joinville method with a few Italian Bastone elements

The first known manual from the academy was published in 1875 and contained a part on the Baton. Several other editions were published until the end of the century and Baton itself continued to be taught to officers until a year before the German invasion in 1940. The Germans, unfortunately, burned most of the Joinville archives in 1918 and again in 1940.

Gymnastic and fencing manual of 1875

In 1912, Georges Hébert published what is considered one of the last great volumes on French Baton from the Joinville lineage: L’éducation physique ou l’entraînement complet par la méthode naturelle. Hébert studied at Joinville and became director of exercises in the French Navy in 1910. He was very dismissive of the instruction being carried at Joinville which was closely modeled on Swedish gymnastics.

Hébert believed in a more “natural” approach to fitness in which training would be practical and mostly centered along natural movements such as those of hunters, farmers, and warriors. His Natural Method inspired the modern movements of Parkour and Crossfit. His manual on martial arts and gymnastics also presents one of the most complex methods on La Canne and Baton.

Hébert gives us one of the most complex and detailed manual on the use of the Baton with many different ways of striking and parrying at a distance, in close or how to disarm and avoid it are all explained in sometimes overly technical jargon; making it quite a challenge to understand. Sources such as these make us understand how limited most of the main military manuals were, compared to the actual richness of techniques being taught.

From peasants to Bourgeois

For a long time, the bourgeoisie had been one of the principal clientele of fencing halls in France. Noblemen would prefer private lessons while the Bourgeois came to train and socialize in these establishments. The 19th century saw a change in the training, as weapons once considered of a low class were now all the rage. The saber took more and more importance while the cane and Baton were now much more popular.

The opening of the Joinville School created a certain rift between the civilian and military masters. While few of the civilian masters published material on the Baton, some briefly mentioned it in their manuals, sometimes mentioning that cane and Baton used the same techniques, only with a different number of hands, in the same way that the military manuals did. It also made its way in the gymnastic curriculum of many French schools, who were teaching it alongside fencing, savate, and cane.

We know little about how their method differed from the military one, but it seems likely that it was quite close. One of the first to publish his method was Pierre-Marie Le Guénec in 1886 who is basically presenting the same method as Joinville’s. For a different outlook, we have to wait for Émile André in 1904 who is still quite close to the military Baton.

Émile André’s manual

“Hit First” and “The Butcher of the Devourings”: Baton and the Workers’ Guilds

The Baton was not only the exercise of the military or the pastime of the Bourgeoisie. Probably one of the least well-known use of the Baton was with the Compagnons du Tour de France (Journeymen of France’s Tour). The Compagnons is an organization that has been in existence since at least the XIIth century. Their members were to tour France and became apprentices to different masters along the way, in order to perfect their skills in a given trade.

They also acted as corporations, and they would often determine their territory over a certain region by settling the issue over a fight. Groups of hundreds of journeymen, associated to different rites (the complexity of this organization is in many ways close to the Free Masons and many different rites representing the same trades were created independently, leading to conflicts), would assemble and use their trademark sticks to fight.

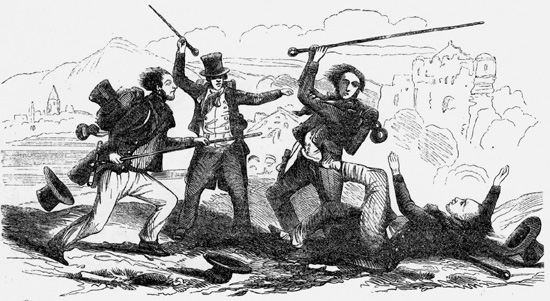

An illustration of a Compagnons fight from the newspaper L’Illustration, 1845

The staves were very long walking sticks; topped with a horn, wood or ivory knob. Many corporations would hire the services of a Baton master who would teach them to use it, or even fight for them. Journeymen would get their very colorful nicknames or noms de guerres (war names) from such fights such as Martinet dit Poitevin “l’Exterminateur des Margageats” (the exterminator of the Margageats), Nivernais “Frappe d’Abord” (Nivernais Hit First), Tourangeau “Sans Quartier” (Tourangeau No Quarters) or Nantais “le Bourreau des Dévorants” (Nantais the Butcher of the Devourings).[7]

In 1806, it came to the ears of authorities that some Parisians Journeymen were opening schools in the art of the Bâton à deux bouts, and that deadly fights often erupted around such establishments. They outlawed the practice several times which, it seems, made the term Bâton à deux bouts disappear in favor of the simple Baton which probably sounded, and looked, much less menacing. [8]

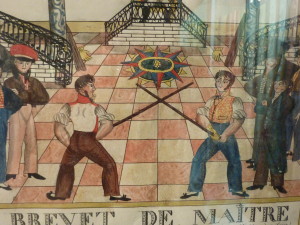

A Compagnons’ certificate of Baton mastery

One of the last mentions of the Bâton à deux bouts was made in 1836 by the Capitaine de Bast, an old “master of all weapons” in Gand. He describes the art of the Bâton à deux bouts as very fearsome and effective, saying how some authors suggest throwing a cape over a battoniste to stop his moulinets, but that to de Bast the Baton “when properly handled triumphs over all resistance”. De Bast also mentions two different styles of Baton, the Paris and Rouen style the latter being preferable to learn in his opinion; as it was much more elegant.[9]

A typical Compagnons’ Baton

The fights dissipated during the second half of the 19th century, as influent Compagnons such as Agricol Perdiguier started to denounce the practice, and that authorities started to repress the practice with more vigor. In 1884, the government also finally allowed workers unions, a role which had been clandestinely filled by the diverse Compagnons rites, giving workers a legal base on which to negotiate… hopefully without the use of the Baton.[10]

A Compagnons shoemaker and his Baton

Surviving traditions and restoration

By the 20th century, several changes started to harm the popularity of French Baton. The first one was the establishment of Olympic Fencing. Indeed, even though La Canne was presented in some of the first Olympic Games, the stick arts were in the end not selected by the FIE as part of their official curriculum. The remaining masters were left on their own to promote an activity which was losing popularity.

A demonstration of Baton in 1950

After the First World War, walking sticks fell out of fashion, and without it the practice of defense with a cane lost its practical appeal. But one avenue remained.

Even though it was at times reformed, Joinville School continued to teach Baton to its students. But this last fortress of the art closed down in 1939; a year before the Germans invaded and destroyed its archives.

Roger Lafond demonstrating some of his Baton method in the 1960s

The art lived on as many teachers were still knowledgeable in its use, but unfortunately, they all did so by altering its techniques. Roger Lafond, a former student of Joinville, created his own method by mixing techniques from Asia and France. It will also survive in a version relatively closer to the original style in the main Canne de Combat federation; through what is now called Bâton Fédéral. Unfortunately, some key elements were also changed by Maurice Sarry, without documenting the process, making it hard to understand what was indeed original and what was modified.

The Canne de Combat Federation’s take on Joinville

A movement is now underway in the Canne de Combat Federation to restore the techniques of the Joinville School, through living traditions and manuals, piloted by professors Philippe Aguesse and Alain Bogtchalian. It is now possible for students to learn this style and acquire ranks in its practice. This movement should be encouraged by the HEMA community, as it represents a rare effort of restoration by a living tradition and a sports federation.

This fight between French farmers became viral in the 2000s and was much ridiculed, but it does show that some of France’s Baton might have survived in other forms in the rural regions of the country. Keep an eye on the man wearing black’s technique.

Update

What are the sources?

Several people asked me what are the sources on French Baton. Here is an exhaustive list of all known manuals and historical sources describing the French style, or being heavily influenced by it.

1660- Paschen – Kurtze Anleitung wie der Baston à deux bous, Jägerstock, oder halbe Pique oder Springestock wie ihn etliche nennen.

1811- Montret – Unfortunately, Montret’s manual remains undiscovered.

1825 – Selmnitz – Bajonet Fechkunst – (De L’escrime a la baïonnette). Selmnitz was a Saxon soldier who served in occupied France in 1814 where he studied fencing and baton. This led him to develop a theory of bayonet fencing (based on his teacher Pinette) which he published. The preparatory exercises include baton. The system includes mostly moulinets and footwork to prepare the arms for handling the bayonet.

1838- Christmann – Theoretisch-Praktische Anweisung des Hau-Stoßfechtens. Although German, Christmann served in Napoleon’s Imperial guard, and presents a version of baton which is extremely similar to the French.

1843- Sokolov – Начертание правил фехтовального искусства (Nachertanie pravil fekhtovalnago iskusstva) Sokolov was the assistant instructor to the fencing master of the Imperial Guard, which until 1840 was Alexandre Valville. His method is similar in many ways to French baton, but focuses on wrist moulinets and includes many original methods.

1862- Riboni – Broadsword and quarterstaff without a master. Northern Italian Bastone styles were heavily influenced by the French military method, and Riboni does mention that his manual explores both French and Italian methods.

Joinville manuals:

1875- L’enseignement de la gymnastique et de l’escrime.

1877- Traité d’escrime pratique au sabre, à la baïonnette et au bâton

1878

1884

1886

1888- Manuel de gymnastique.

1891

1893- Manuel de gymnastique.

1895

1880- Le Guénec – Enseignement de la gymnastique et des exercices militaires.

1886- Le Guénec – Manuel de gymnastique théorique et pédagogique.

1889- Hutton – Cold Steel. Hutton’s manual describes Great Stick, which is more or less a copy of Joinville’s method.

1890-1914 – Delauney

1892 – Ministère de l’instruction publique – Manuel de Gymnastique et de jeux scolaires.

1900- Charlemont – Les sports modernes illustrés, encyclopédie sportive illustrée. Charlemont never wrote on Baton per se, but mentions that his style of Baton is simply cane techniques with two hands. This approach is often taken by authors for whom techniques can be used with both long and short weapons. This encyclopedia article describes his method of La Canne (p.73-92).

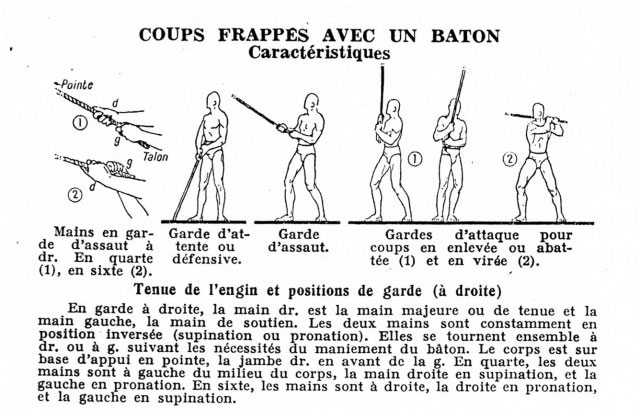

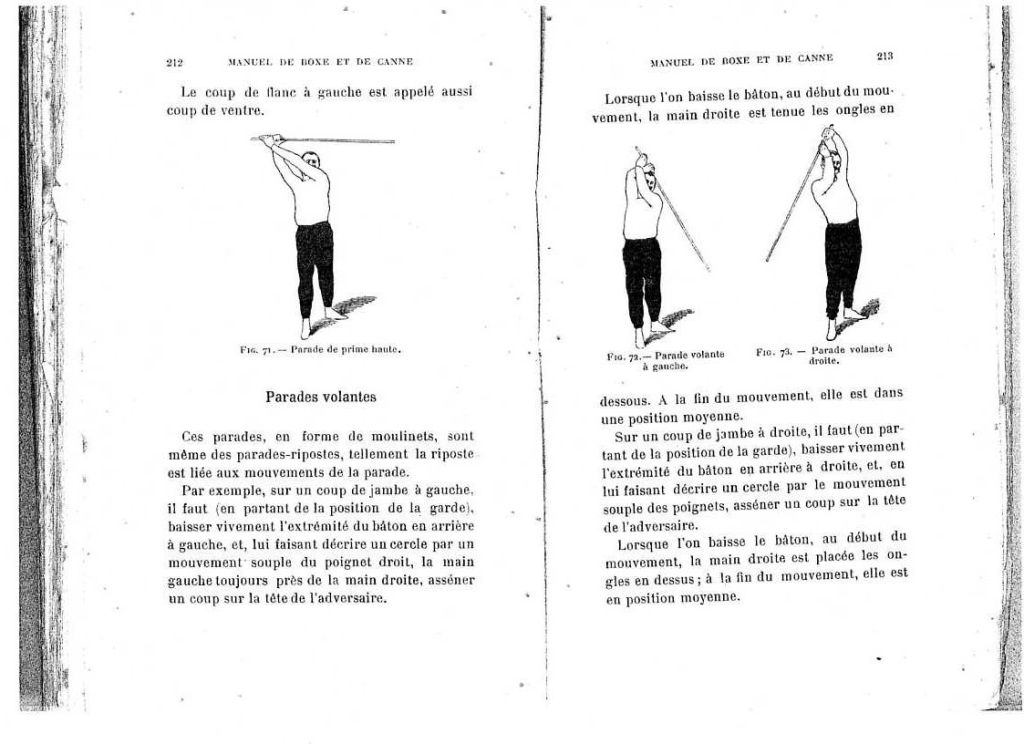

1904- André – Manuel de Boxe et de Canne.

1905- 1935 – Larousse dictionnary. Often attributed to Charlemont, these figures show some of the basic techniques of Baton.

1908- Traité de canne, boxe et bâton.

1910- Hébert – L’éducation physique ou l’entraînement complet par la méthode naturelle

1914- André – 100 façons de se défendre dans la rue avec armes.

1929- F.G.S.P.F – Étude schématique des exercices imposés.

[1]BARDIN. Dictionnaire de l’armée de terre ou recherches historiques sur l’art et les usages militaires des anciens et des modernes. 1851, p. 699

[2] Mémoires de l’Académie de Vaucluse, 1882, p. 334

[3] P Brioist, H Drévillon, P Serna. Croiser le fer: violence et culture de l’épée dans la France moderne, XVIe-XVIIIe siècle. Champ Vallon, 2002.

[4] Ibid, p.194

[5] HUTTON, Alfred. Fixed Bayonets. William Clowes and sons, London, 1890.

[6] Premiers Maitres d’Armes en Russie. http://escrime-avenir.org/cntnt/fra/fehtovanie8/fra_history/rossiya.html

[7] http://la-rose-couverte.over-blog.com/pages/Le_Compagnonnage_Videos-1668436.html

[8] http://www.crcb.org/le-baton-a-deux-bouts-interdit-aux-compagnons-de-tours-en-1806/.html

[9] http://www.crcb.org/batons-et-fleaux-defensifs-1836/.html

[10] http://compagnonnage.info/blog/blogs/blog1.php/2014/10/22/rixes-compagnonniques-en-eure-et-loir

thank you for writing this long and good overview of baton. it looks like the Hébert source is down and i couldnt find an alternative to it. can you provide the pdf or a second source ? thx

http://documentslide.com/documents/hebert-canne-baton-methode-naturelle.html

” in 1205 Phillip II ruled that the bâton d’armes (arming staff) was to be three feet long (corresponding at the time to the height from the floor to the armpit) ”

Am I misunderstanding something or is this claiming people were four and a half feet tall less than a thousand years ago?