Next to the sabre, the walking stick is probably the most popular weapon of all 19th century martial arts. While the longsword basks in the mythology of the knight, the rapier behind the cape of the musketeer and the sabre in the panache of the hussar, the cane brings us outside or perhaps at the fringe of the warrior image. It presents a much more relaxed and probably sleeker image than that of the boiling duelist, carrying a discreet weapon ready to stop in its track any unsuspecting footpad. This popular image is possibly what makes cane such an interesting art for many people

When we talk about cane fighting, one thing that comes to the mind of many people familiar with the subject is La canne. La canne de combat is still a sport practiced today by thousands of cannistes around the world, but it has changed since it’s glory days. In this article I will explore the history of cane fighting in France, its most renowned masters and how it enjoyed popularity in many corners of the world.

Before La Canne

We have many historical instances of people using walking sticks as self defense since the dawn of time, and pastoral societies everywhere use their walking sticks as weapons. It is then difficult to establish a starting point to this practice, even in a country such as France. Stick fighting traditions existed all over Europe at the time, and it is certainly possible that when carrying a cane people used it in these respective fashions. The Bretons for example were quite famous for carrying their sticks, which was not necessarily meant for walking around as it was most often carried by a leather thong on the wrist. Unfortunately, we do not know what this style looked like as it apparently disappeared a long time ago.

A Breton carrying his Penn Bazh around his wrist, as was customary. Galerie Armoricaine. Costumes et vues pittoresques de la Bretagne. Nantes, Charpentier Père et Fils, 1848.

It is also quite possible that many used their skills in the bâton à deux boûts learned in fencing salles until the end of the 18th century. Many walking sticks were the size of small staves prior to the 19th century and could easily have been used two-handed like a bâton.

We have good reasons to believe that like the bâton à deux bouts, la canne existed already in some form with the working class. Diderot tells us that up until the 18th century, peasants and bourgeois would fight in events called behourd in the day of Lent with “sticks and staves”. The practice was apparently kept alive in Italy, where it was called bagordare, an in Spain where the name was interestingly cannas.[3]

A fight between two groups of Compagnons in Nantes, 1699

The appearance- or at least documentation- of the cane as a weapon will come in a time of great social upheaval in France and by extension most of Europe. While the authorities since Henry IV had tried to curb or even extinguish dueling, the carrying of the sword was loosely contained because of how royal authority translated into laws. Many cities like Paris enacted edicts against the wearing of swords by commoners, but in other regions these laws were unknown or at least much tamer.

It is only with the advent of the Revolution that sword wearing will take a hard blow. The new State, later bolstered by the Code Napoleon, will extend it’s authority and remove the right of sword-carrying to noblemen, restricting it rather to the military and policemen.[5]

The image of the gentleman was changing. Political will was not ascertained through might but through communication and debate. The gentleman was now not so much a soldier than he was a scholar, but although he could no longer carry the sword he would not go to town unarmed.

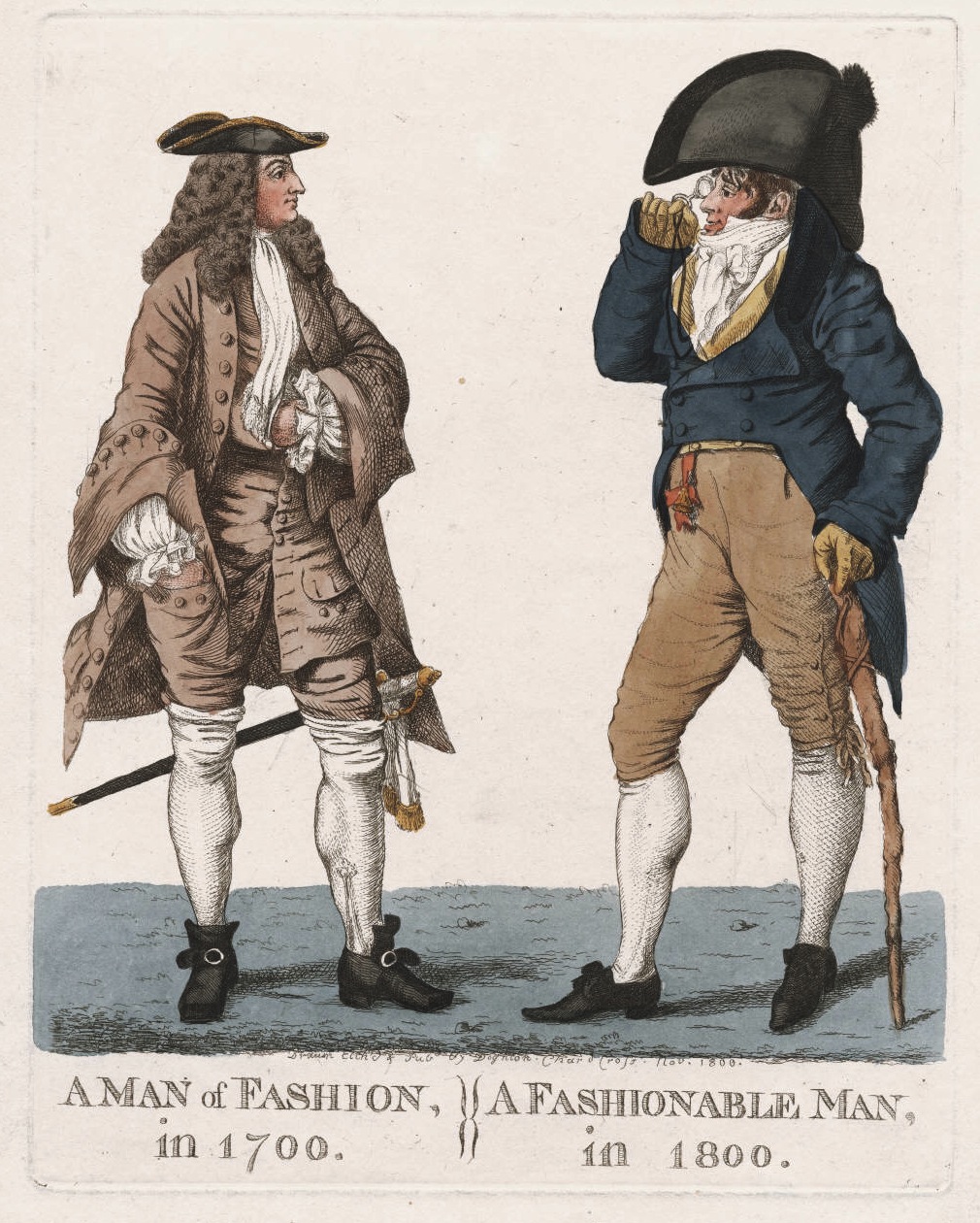

While we often see 1700 men fashion as tidy and effete to the extreme, in reality, its early iteration had more of a calculated unkempt and dysfunctional attitude. The gentleman on the left wears his clothes haphazardly, his socks intentionally sagging, hands in his pockets or in his vest and his sword dangling at his knees in a cavalryman fashion. The man opposite to him exemplifies the style of the turn of the century “Incroyables”. His clothes are tailored to fit, are impeccably worn, and while he is well dressed he exhibits a taste for the grotesque: an oversize hat and clothes made to hide deformities. He carries a lens to exemplify his observing and scholarly attitude but also carries a mean looking knotty cane, or club, used as a weapon in confrontations with opposing political groups.

While we often see 1700 men fashion as tidy and effete to the extreme, in reality, its early iteration had more of a calculated unkempt and dysfunctional attitude. The gentleman on the left wears his clothes haphazardly, his socks intentionally sagging, hands in his pockets or in his vest and his sword dangling at his knees in a cavalryman fashion. The man opposite to him exemplifies the style of the turn of the century “Incroyables”. His clothes are tailored to fit, are impeccably worn, and while he is well dressed he exhibits a taste for the grotesque: an oversize hat and clothes made to hide deformities. He carries a lens to exemplify his observing and scholarly attitude but also carries a mean looking knotty cane, or club, used as a weapon in confrontations with opposing political groups.

The cane was already present in the noblemen fashion of the 1700s, but the 1800s elevated it to the status of a necessity. It was the new symbol of the gentleman walker, exploring his environment and observing it, but always ready to defend himself.

We can imagine that this created a problem for fencing masters. While fencing was still practiced, it did not enjoy the same necessity among the remaining aristocracy and as a result not the same attraction towards the newly empowered bourgeoisie. Some enterprising masters then chose to capitalize on this change of fashion and translated their skills in the use of the walking stick or la canne.

But as the use of the stick was mostly the specialty of the working class, it is no surprise that the first few teachers hailed from their ranks and that it did from then on enjoy the companionship of Savate which was also an art of the people. One of the very first recognized teachers of the art was Michel Casseux dit “Pisseux”.

Michel Casseux

Michel was born in 1794 in the Parisian quarter of Courtilles, a violent neighbourhood full of dance halls and cabarets frequented by shady characters.[6] He soon became the terror of Courtilles which will land him in prison a few times. He eventually opened a Savate salle which soon started to enjoy some popularity. His methods were brutal, and for a few coins he could teach how to “cut the tongue with an uppercut, or pop an eyeball with a punch”. Kickboxing was not the only art taught there as a variety of weapons were also practiced; among them the seven branch flail, the bâton brisé (peasant flail), the biscaïen (I haven’t found any satisfying definition of what a biscaïen could be. Technically, it is a large bullet, but in this case my best guess would be some sort of flail or cudgel) , the baton and the cane.

This lithograph possibly shows Michel Casseux, on the right, giving a lesson of savate. It was made in 1843 by his student Paul Gavarni. The man fits with the description of Michel’s thin, pox-marked body, and the legend shows his colourful language: “Never let a man walk on you, cut him in his march… Remember the fourth division, back up, parry, riposte! Hot!… Break up his leg, that’ll make him mad. Good!… The lower part now roughed up, work on the top one!…”

While Michel never authored a manual on his method, we owe to one of his students the first manual of La canne and savate in 1843. His method is quite different from subsequent masters. The cane is held mostly on the left shoulder instead of in a sabre-like tierce, off hand to the back, in a position that is quite close to that demonstrated nearly 20 years later in the canne royale manual of Eugène Humé. It also seems that the art depends not so much on lunges, but rather on steps and half steps like the Joinville method. It could be explained by the fact that Michel’s method seems mostly concerned with fighting multiple opponents, which is why it shares commonalities with Leboucher’s bagarre (brawl) section.

Two lithographs showing lessons in the salle of Michel. these were made by Gavarni, one of Michel’s most famous students in 1843. Source: Digital Commonwealth.

But if it was to enjoy any popularity, the art needed to sell itself as more respectable, and so Casseux opened a salle in 1847 on Buffault street in Montmartre. Savate and canne were then all the rage, and many of Paris’ high society assembled at his salle. He also gave private lessons to the Duke of Orleans and Lord Seymour, and other celebrities like Théophile Gauthier or Gavarni attended his classes and mentioned him in their writings.

The methods taught in these schools proved efficient, sometimes too much, as shows the case of Jean-Gaspard Deburau who killed a young man harassing him in the street from a single moulinet to the head in 1836. Deburau being a famous artist, the case was widely followed by the Parisian public, and brought attention on the fledgling art of la canne. Deburau was eventually acquitted, but never again carried a cane with him.

Although Michel is often credited with being the creator of modern French martial arts, other teachers taught at the same time such as Gousset or Moufflet but are now virtually unknown.

Michel’s star soon faded, perhaps unable to compete with other younger professors for which he had paved the road. His former students provided for him from time to time, but he died poor at 75 years old, forgotten by most.

Larribeau

Not much is known of Larribeau, even his first name seems to remain a mystery but he is one of the oldest masters of La canne that we know of that published a manual on his method. Born in 1776, Maître Larribeau was a Napoleonic veteran with a bittersweet experience, as he survived not only Trafalgar but also the wreckage of the Méduse (Larribeau’s nickname was “the Méduse’s Scrap”). We know from the memoirs of Ducor, a sailor from Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, that sailors were known as being very proficient in the use of the baton, flail and cane, and that following the war many of them opened up fencing salles where all the weapons were being taught.[7] It is complicated to know how much of Larribeau’s method can be traced back to the Napoleonic wars as he published his manual only in 1856, but by then he claimed to have been teaching for 40 years, after having been a sailor for 20.[8]

Larribeau’s portrait in his 1856 book

He opened a salle at rue Montholon, 109 rue de la Harpe, and at 13 bis passage Verdeau, where he taught not only cane but also baton, boxing, fencing, wrestling and even shooting. This method puts a strong accent on self-defense, and even developed a patented “pocket cane” of which we, unfortunately, know nothing else than the name. Possibly this was some sort of folding cane that could be carried in one’s pocket.

His method is in line with other authors of the time, although Larribeau puts a stronger focus on power generation and exercising on bags and pads, some of them equipped with anthropomorphic heads.

It is currently unknown when Maitre Larribeau passed away. After retiring, he gave his salle to Louis Leboucher.

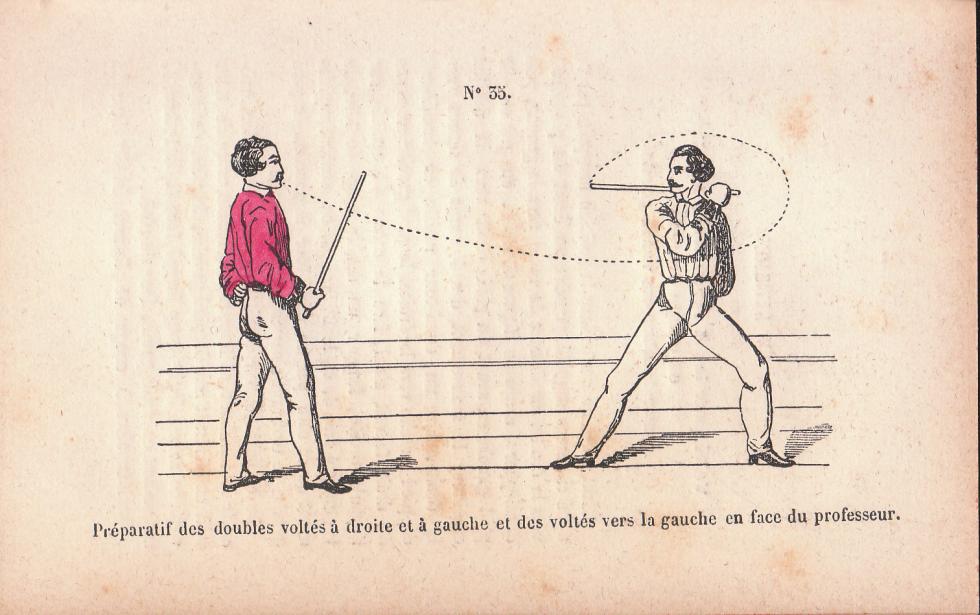

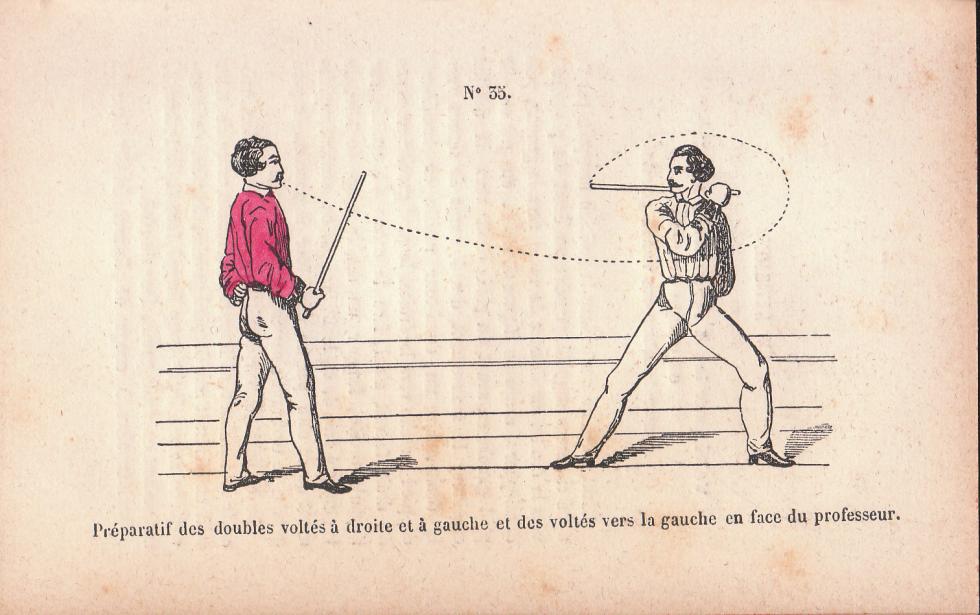

Preparation to the voltes from Larribeau’s manual. This is also part of Leboucher’s method, and seems to be a link with what Michel was teaching with the cane resting primarily on the shoulder.

Louis Leboucher

Louis Armand Victorien Leboucher is one of the most famous figures in French martial arts during the 19th century. Born in Rouen in 1807, he moved to Paris where he followed the instructions of Michel and the Lecour brothers and opened his own salle at 20 rue de la michodière before taking over Larribeau’s and Michel’s. Between 1855 and 58, Leboucher maintained four separate salles in Paris.[9]

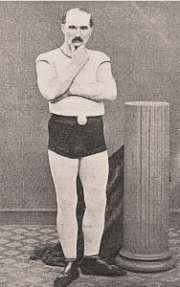

Louis Leboucher

Leboucher was a man of short stature at 1m65 but compensated for his shortness with an aggressive style. He was known for his uncompromising attitude towards training as Joseph Charlemont tells us in his memoirs:

“Leboucher was the innovator of combat boxing; his teaching was brutal and instinctive; you would go to him mostly to learn how to defend yourself against footpads and other characters of the same genre; he taught you how to defend yourself against a bounder, how to correct a brutal coachman. He knew by heart (probably because he actually used them) all the strikes more or less roguish and had for them unexpected parries and surprising ripostes.

He encouraged his students that made practice (as he said) to “once in a while go into some wretched public dance halls and try to duff up with some rascals.”[10]

He also had a separate method called the “canne du voyageur” (cane of the traveler) which he taught to individuals passing by and wishing to learn a simple and effective method. It is probably this method which is included in his 1843 manual, one of the first ever published on the subject. Indeed, his book seems extremely basic and clean and far from the brutal tricks that his students tell us he taught.

“Leboucher, professor in Paris” as signed on Joseph Charlemont’s diplomas

Leboucher was very much interested in boxing and wrestling, of which he included many techniques in his repertoire. He was known as a very apt demonstrator, but few wanted to fight with him publicly for his aggressive nature led to painful outcomes. His drinking habit coupled with his irascibility made it hard for him to retain clients, some he would even intentionally drive away, but he nonetheless instructed many celebrities including Théophile Gautier, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas and Honoré de Balzac.

Of all the masters, his method was probably the one that left the most enduring trace being the basis for what would become Charlemont’s style. In fact, Leboucher was one of the masters who signed Joseph Leboucher’s canne and sabre diplomas. Some of his principles can still be seen in canne de combat today.

He passed away at the age of 59 in his salle, on the 7th of September 1866.

The engaging guard from Louis Leboucher’s manual on La canne. The link with sabre fencing is at this point a lot more evident and might have been a change implemented by the Lecour brothers.

My own interpretation of the baisc techniques from Leboucher’s manual.

The Lecour brothers

Charles and Hubert Lecour are not quite as known today in the world of La canne, possibly for the fact that they left us no manual, but in their days the Frères Lecour were arguably the most successful teachers in France. Charles was born in Moisery, and started to learn savate at Michel’s school when he was 16 years old, as well as canne and baton at Leboucher’s. Charles was also famously responsible for bringing English Boxing techniques in Savate.[11]

In 1830 he opened up a first salle in Montmartre. With his brother, he opened another salle at the Passage des Panoramas which was aimed at the upper class. He stripped Michel’s savate of its more brutal techniques and renamed the practice Chausson. This was especially useful for them under the Second Empire, when in 1856 the Empress Eugenie banned French boxing for its brutality. Most instructors then used the name adresse française and mascaraed their demonstrations as musical choreographies. The interdiction was ultimately lifted in 1860.

Hubert’s specialty was the cane, and he succeeded as an instructor to his brother in 1848. He simplified the style and concentrated on speed and precision. He is often cited as being able to launch 100 hits a minute and developed a style with which someone could fight in an apartment corridor.

What made the Lecour brothers’ formula a long-lasting success was their understanding of bourgeois and aristocratic culture, as well as the rise of organized sports in France. They popularized the formula of “assaults-concerts”, where fights and demonstration were given to the public along with a musical accompaniment (not unlike many modern demonstrations). Such demonstrations brought in most of Paris’ elite.

An ad for the classes of Hubert Lecour. You can see cane and baton in the background, as well as a striking dummy in the right corner. Note also the use of gloves and fencing masks for the boxers.

Louis Vigneron

Vigneron was born in 1827 in Paris.[12] He served in the army, and quickly rose up through the ranks of French boxers and cannistes and acquired quite a reputation after defeating one of Lecour’s students, Rambaud, in 1850. He opened a salle in Ménilmontant before installing himself at 6 Waux-Hall street. In 1854, he won the first public bout between savate and British boxing against Dickson. He was finally defeated by his own student Joseph Charlemont in 1867 in another public bout. Vigneron gave many daredevil performances on the street of Paris, namely an exercise of shooting an artillery gun held on his back. This specific stunt cost him his life in 1871.

Louis Vigneron

Joinville Le Pont

As I already discussed in my article on French bâton, the French Army had for a long time taught fencing with a vast array of weapons, including the walking stick, but many different methods cohabited as each master taught his own formula. In an effort to normalize the instruction of fencing and gymnastics, the military opened the Joinville-Le-Pont School in 1851 where a universal system of physical education would be created. Cane was being taught in conjunction with baton, and in fact the two methods were so closely related that the gymnastic manuals produced by the school simply tell us to use the same techniques with few differences. Photographs and even early videos though show us that the breadth of techniques was probably higher than those manuals suggest, and some other military men give us more details such as Delauney or Hébert. The instruction in cane continued in Joinville until the Second World War.[13]

The Joinville style is quite different from most civilian styles. As with the baton, none of the parries are given point up, although they are sometimes made with hands apart, strikes can be given with either hand and the footwork goes beyond the usual lunging footwork using also steps, half steps and jumps.

This chronophotograph was taken by George Demeny in 1891 at Joinville. It was part of an experiment to measure the speed of different types of stick strikes. The man on the left uses direct back and forth strikes, while the one on the right uses circular motions. It was discovered by Demeny that the cane travelled at the same speed in both cases (as long as it was a light cane with little forward weight). It is also interesting to see techniques that are not shown in Joinville manuals, such as a parry using the lower portion of the stick, which is alluded to in other military manuals focusing on baton.

Joseph Charlemont

Charlemont was born in 1839 in a peasant family of Northern France.[14] His family moved to Paris to escape poverty, making Joseph live a difficult childhood. At the age of 17 he joined the 2nd African Zouaves and subsequently the 19th Chasseurs à pied. It is there where he met Louis Vigneron who taught him boxing and La canne.

Charlemont’s prevost diploma as given to him by Vigneron in 1863 and, as was the custom, signed by many other attending masters including Leboucher and Charles Lecour. His contre-pointe (sabre) diploma was given in 1866, by his professor Tessier, and contains most of the same signatures.

In 1869, Charlemont left the military life and opened a salle where he taught savate, bâton and canne. In 1871, he joined the cause of the Paris Commune and its federated battalions. This was short-lived, and following the violent repression of the Commune in 1872 he escaped to Belgium to flee a death sentence. He opened up a salle in Brussels, and is credited by many for popularizing savate and canne in the country. He came back to Paris in 1879 and along with his son Charles developed a strong community of cannistes which is allegedly said to have numbered around 400 000 practitioners in the whole country by 1914.[15] He published a book in 1899 which contains both boxing and cane. His son ultimately took over the family business, although it seems from court records that this was not done without difficulties and the two became estranged.[16] Joseph passed away in 1929.

Joseph Charlemont’s portrait in his 1899 book

Charles Charlemont

A giant figure in the world of French martial arts, Charles Charlemont was born in 1862. He gave his first public fight at the age of 9, and following in his father’s footsteps became the most important actor in savate and La canne. Charles and his father had a similar approach to fighting, one which put power generation at the forefront. Even though all their predecessors used a certain amount of development in their techniques, the Charlemonts will bring this concept to its extreme with deep positions to power blows.

Charles Charlemont

They are often credited with the sportification and normalization of these arts, while Charles brought his approach to the ring and developed long-standing rivalries, namely with Pierre Vigny of Bartitsu fame.

After the First World War, Charlemont became the main figure of savate and La canne, with few other competing approaches remaining. He continued to teach until his death in 1944, but by that time the art was only practiced by a handful of students.

This first video was shot in 1900 and showcases Charlemont (on the right) with a student demonstrating some of the basics of his style. This is virtually the same system devised by Charlemont’s father.

This is another demonstration showing some of the combination drills practiced by Charlemont’s students in 1928. Note the voice of Charlemont calling the actions.

Pierre Vigny and Marguerite Sanderson

Pierre Vigny is the originator of the walking stick method found in Bartitsu, a style he developed with his wife Marguerite. Vigny was born in 1866 in Paris, and 20 years later joined the Second Regiment of French Artillery at Grenoble where he obtained the title of maitre d’armes.[18] He left the army around 1890 to open up a boxing academy in Geneva, along with his wife Marguerite, herself a long-standing fencing champion.[19] In 1892, he opened the fencing salle at Evian-les-bains, near Grenoble on the French side. At some point between 1898 and 1899, Pierre and Marguerite moved to London and joined the Bartitsu Academy of Edward William Barton-Wright to teach La canne and savate. In 1903, he opened his own school in London and trained recruits at the Aldershot Military School before moving back to Geneva in 1912. The mention of “Baritsu” (likely a typo) in a Sherlock Holmes story and the recent rediscovery of the style catapulted Vigny out of total obscurity, and is now one of the most popular styles of historical la canne.

Vigny in a now famous pose, inviting an attack to the hand.

Yet, not a lot is known of Vigny’s method compared to others. A few articles were published on it in 1902 in the Pearson Magazine, but it inspired a lengthier book in 1923 by H.G. Lang, a police officer serving in India.

Lang’s method is different in many points from the more mainstream schools of La canne. First of is its use of many engaging guards not commonly found in these manuals, such as high hanging guards. That said, there are also many similarities, especially with the military cane which Vigny undoubtedly received ample training in. His use of a two-handed high guard is described by Lang as having a Caribbean origin but is also present in some La canne manuals. His two-handed strikes and tip down guards are also highly reminiscent of the Joinville method.

Pierre Vigny as a fencing instructor in Evian-les-bains. 1898 – La vie au grand air

Marguerite Sanderson (Vigny) at the club Hoche in 1908. Gallica.

Émile André

Émile-André Raballet was born in 1859 and spent most of his life as a journalist, writing in sports columns and fencing publications. André was a renowned duelist, having fought his first duel at the age of 20, and went on to apparently fight many more, which explained his numerous writings on the subject.[20]

Cane vs. knife from Émile André

What André left us as far as La canne is in line with his general approach to martial arts, a mix of sport and combatives. His approach is unique for the time for his short footwork and developments which are closer to modern canne de combat in many ways. André suggests that in self-defense, one should start with short quick strikes and continue with more powerful and developed strikes when he is able to.

Jean Joseph Renaud

Renaud, along with André, is another member of what is now known as the “Défense dans la Rue” movement. A mix of jiu jitsu, French martial arts and new approaches to combatives. Renaud was born in 1873 in Paris, and carved quite a reputation for himself in fencing, participating at the Olympic Games of 1900 and 1908. He also officiated at 100 duels and wrote close to 60 novels.[21]

Renaud is contentious in his propositions. While most authors suggest to develop the strikes to a degree or another or to use short jabs when needed, Renaud suggests using only short direct hits, in the manner of a jab. He is, as far as I know, the only author to recommend this approach.

Renaud passed away in 1953.

Jean Joseph Renaud showing his self defense attitude with a cane.

Georges Hébert

Hébert was born in Paris in 1875 and grew up to become an officer in the French Navy. While stationed in Martinique in 1902, Hébert happened to witness a volcanic eruption for which he was put in charge of the rescue and evacuation of the inhabitants. This experience came to shape his vision for a utilitarian type of physical training: “Being strong to be useful”. He also saw active service during the First World War, where he was wounded while leading men in Belgium.[22]

Hébert was trained in the Joinville method and became a physical instructor to the troops stationed in Lorient. This is where he came to develop his method that he called the Méthode naturelle, or Natural Method. Very critical of the dominant Swedish gymnastic culture of the day which he saw as artificial, unable to develop the body harmoniously and to prepare students with the practical demands of life.

Hébert’s method of la canne

In his vision, self-defense was a major part of that approach. Hébert began to publish several volumes on his method, one of the first, L’éducation physique ou l’entrainement complet par la méthode naturelle, contained savate, wrestling (on land and water) and jujutsu, but no weapon work although it was undoubtedly part of his method. It is only by the end of his life, that he will include cane and baton as part of a massive 5 volumes work which started to be published in 1941. Although published quite late, it is most probable that these volumes represent a much earlier view on Hébert’s method.

Hébert functions in a very similar progression to Joinville . Starting with baton and applying most of the curriculum to the single-handed cane, in contrast to most civilian teachers who started with the cane. It is one of the richest methods in terms of movements and Hébert goes quite far in describing the various motions possible while always keeping a very practical view on the subject. His method almost became the official French one, poised to replace the Joinville curriculum. But with the advent of the First World War everything was put on ice and the project never quite flourished. Yet, his influence in military physical education across the world is undeniable.

Hébert passed away a few years later, but his legacy still holds today as some of his training regimen is still followed in many military and police forces around the world. His approach also inspired movements such as Parkour or Crossfit.

Hébert as a commander in the French Navy

Roger Lafond

Maitre Roger Lafond was born in 1913 in Paris. In 1933, Lafond joined the military and was sent to the Joinville battalion. In 1939, he was sent to the front where he was made prisoner by the German army. For the duration of the war, he continued training in prisoner camps with other French soldiers. Following the liberation, Lafond went on to finish his maitre d’armes training and became a savate, cane and fencing instructor.[24]

He rapidly started to train in the newly introduced Japanese martial arts with the likes of Hiroo Mochizuki, Tsutomu Ohshima and Tetsuji Murakami.[25] The skills learned with these karate and aikijutsu instructors came to color his particular style of self-defense which he named Panache. The method was taught famously to the actors of The Avengers TV series.

Roger Lafond taught until the age of 95 and passed away at the age of 97 in 2011.

A short documentary from the 1960s showing Lafond’s style.

Bernard Plasait

Plasait is one of the main figures behind the renewal of savate and La canne. He pioneered a new approach which was faster and more acrobatic than the previous ones. He published his method in 1971 in his book “Défense et illustration de la boxe française”. His influence is mostly felt in savate, and although his approach to La canne did not quite flourish, it served as a strong inspiration to others, including Maurice Sarry. Twice champion of France in savate, he helped to create the modern federation of French boxing. Mr. Plasait now practices out of Nîmes in southern France.

This video shows two of Plasait’s students (including his sister) demonstrating his method for sport and self-defense

Maurice Sarry

When the young Maurice Sarry began La canne in the 1960s, there were many salles still teaching, but only to a handful of students. The art was fading out, but Sarry had a great interest in it. In 1975, he created the National Committee of Canne and Baton and published a book on his new method in 1978. In 1986, the first championship was held, and La Canne now had 3000 practitioners.[26]

The method that Sarry created was a lot more acrobatic than the previous ones, while still preserving some of the key principles such as the development. Sarry found a way to keep the method safe, while also keeping some of the realism by mandating that each strike be sufficiently developed. But apparently Sarry was not quite happy, and in 1986 he left the committee he had created.

La canne de combat demonstration in 1986 in Nantes.

He went on to continue his own studies, creating a new style called canne fouet (whip cane) which is close in many ways to kali and to a certain extant to the methods of Michel and others. He also experimented with peasant weapons such as the pitchfork.

Unfortunately, Sarry died relatively young in 1994, and left very few documents behind to help us understand how his method was developed the way it was. We do not know who was his teacher, although he gravitated around Count Baruzy, one of Charlemont’s former students and most likely learned Charlemont’s method which was the most popular at the time.

Maurice Sarry in his later days practicing bâton.

La canne today has become more and more complex. Not only do we find the competitive canne de combat scene, but along this you also find more or less official canne défense systems which try to incorporate elements of modern self defense to canne de combat. Along this, you also find historical interpretations, some of them done through the canne de combat federation such as the Joinville Baton recreated by experts such as Alain Bogtchalian and Philippe Aguesse, but also other recreations by HEMA enthusiasts (such as myself).

Sources

To finish, I have included here a list of the major manuals including La canne. Note that I did not include manuals which cover only self defense tricks, only those presenting a full system. Also, I included only the manuals which show a clear French influence.

1843 – Anonymous (Student of Michel)

1843- Leboucher

1856 – Larribeau

1875- Joinville School

1890- Delauney

1892 – Manuel de Gymnastique et de jeux scolaires.

1899- Charlemont

1902- Vigny

1902- André

1912- Renaud

1919- Chromie

1923- Lang

1929 – FGSPF

1941- Hébert

1971- Plasait

1978- Sarry

Bibliography

[3] L’Encyclopédie, 1re éd. Texte établi par D’Alembert, Diderot , 1751, Tome 2, p. 192.

[5] Pascal Brioist, Hervé Drevillon et Pierre Serna. Croiser le fer : Violence et Culture de l’épée dans la France moderne (XVIe-XVIIIe siècle). Champ Vallon, 2002.

[6] Charlemont, Joseph. La boxe francaise historique et biographique. Paris, À l’académie de boxe, 1899.

[7] Ducor, Henri. Aventures d’un marin de la Garde impériale. Paris, 1833

[8] Charlemont, Op cit.

[9] Charlemont. Op cit.

[10] Charlemont. Op cit.

[11] Charlemont. Op cit.

[12] Charlemont. Op cit.

[13] Pierre Simonet, Laurent Véray. Les Cahiers de l’INSEP/ Hors Série: L’Empreinte de Joinville, 150 ans de sport. INSEP Éditions, 2003.

[14] Charlemont,. Op cit.

[15] This number is often cited, but I have not been able to verify it.

[16] Taken from a discussion with Philippe Aguesse who examined the archival records concerning the Charlemonts.

[18] Marguerite Vigny (a.k.a. “miss Sanderson”) Competes At the Cercle Hoche (1908)Bartitsuka – http://www.bartitsu.org/index.php/2017/05/marguerite-vigny-a-k-a-miss-sanderson-competes-at-the-cercle-hoche-1908/

[19] La Vie au grand air. 15 October, 1898, p.166.

[20] FFAMHE. Émile André. https://www.ffamhe.fr/wiki/%C3%89mile_Andr%C3%A9

[21]Picq, Gilles. Un gendelettre oublié. Cahier Mirbeau, no. 13, 2006.

[22] Delaplace, Jean-Michel. Georges Hébert, sculpteur de corps. Paris, Vuibert, 2005.

[24] Hamon, Fabien. Se défendre avec Panache ! Vie et méthode de Maître Lafond. Le Perreux-sur-Marne, Association Méthode R.&J. Lafond, .

[25] Hamon. Ibid.

[26] Rose couverte – canne française et bâton. Maurice Sarry (1935-1994). – http://la-rose-couverte.over-blog.com/pages/Maurice_Sarry_19351994-1499625.html

Thank you to Maître Philippe Aguesse for compiling a lot of information on la canne. I am glad to count him as a friend, and would suggest to anyone with an interest in the history of this art to stop by Philippe’s club in Anthony.

Thanks for the link to the Renaud translation. There’s a newer one available here, though:

https://www.lulu.com/shop/jean-joseph-renaud/defence-in-the-street/paperback/product-22992068.html

I’d very much recommend that those who speak French look at the modern reprint in the original language though – much better:

https://emotion-primitive.com/livres-arts-de-combat/3625-la-defense-dans-la-rue-9782354221133.html