What is Irish stick fighting?

By Maxime Chouinard

You’ve probably heard of Irish stick before or at least if you clicked on this article you are no doubt curious about what it really is. The art called bataireacht or boiscín is a particular martial art, not only because of its history but also because it has only recently begun to rise back from nearly total extinction. It is known around certain circles such as Historical European Martial Arts but even in Ireland you will find very few who know of its existence and even fewer who practice it.

Where does the name come from? Bataireacht is found in the 1959 Irish dictionary of the famous Irish language scholar Tomás de Bhaldraithe. No clear explanation is given on its origin, but Bhaldraithe translates it plainly as “singlestick”. While bata usually refers to a “stick”, reacht being the equivalent to “ing”. Bataireacht would then be the “sticking” or “cudgelling”. Boiscín can be translated as “fencing” according to the 1977 dictionary of Niall Ó Dónaill. This relation to fencing does not necessarily mean a connection to sword-fighting; as fencing could be used at the time to denote other martial arts aside from swordsmanship.

This article is meant as a complete basic overview of the history and practice of Irish stick. It will be part of a book to be published on the subject of the history and techniques of this art.

Source: Sean Sexton Collection

1. Deep roots

like many old martial arts the origins of Irish stick are extremely hard if not impossible to determine. Mankind has been using sticks for centuries and clubs similar to those used in bataireacht were found in Bronze Age archaeological excavations[1]. It is even harder to document the early history of Irish stick because of the people who practised it; or rather those who didn’t.

Like many stick fighting arts, bataireacht was a vernacular fighting art. It was practised mostly by the working class, and only started to attract the attention of the elites – who were most of the time the ones responsible for written history – by the mid 18th century, at a time where the practice of stick fighting among the working class of the rest of Europe was becoming rarer and that violence as a source of enjoyment began to be frowned upon; especially by the upper classes.

It is believed by some that the Penal Laws were mostly responsible for its appearance. The Penal Laws were a series of rules enacted by the British Crown following the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The Irish Catholics had throughout the 17th century attempted several uprisings and the British were keen on putting an end to it. The laws were especially targeted to remove most powers of rebellion from the Catholics: No right to own any land, no right to own horses of a certain height (i.e. warhorses), could not serve in the military and, of course, had no right to own any weapons. The respect of this last rule was insured by Protestant raiding parties who randomly inspected villages in search of hidden weapons. It is said then that the Irish simply chose to carry walking sticks that could double as clubs, the famous shillelaghs, to avoid being accused of possessing weapons. This theory follows a similar popular belief that the people of Okinawa started using farm implements when the Japanese banished weapons, a theory which is not entirely true as this ban concerned mostly firearms.

While the Penal Laws probably made the shillelagh a much popular option for self-defense, it cannot explain the fact that Protestants were also known to use it or that similar weapons were used in other parts of Europe where such laws were non-existent.

It is also said that boiscín might have appeared as a way to train potential soldiers for service in the Wild Geese regiments. Until the 1793 Catholics were banned from serving in the army. Irish mercenaries were known since the Middle Ages to fight in Continental armies, but in the 18th century, it became a common solution for many, especially sons of Irish Gentlemen, to serve in French, Spanish, Austrian, Italian, Polish and even Swedish armies. But again it does not take into account the Protestants who were using shillelaghs and does not consider that at this time a prospective soldier would have spent his time in a much better way by learning how to march in formation and shoot than to fight with a stick (even if training for swordsmanship) considering that the gun now dominated the battlefield. It also shows a misunderstanding of how fencing was taught in armies of the time. Fencing would be taught by fencing masters and prevosts, of which a regiment could contain many or none at all, but only for a fee. A commanding officer could, if he desired, pay a master to teach some of his soldiers, but most of the time such instruction would be sought and paid for by the soldier himself. This model was quite different from the generalized instruction we could see by the time of the First or Second World Wars.

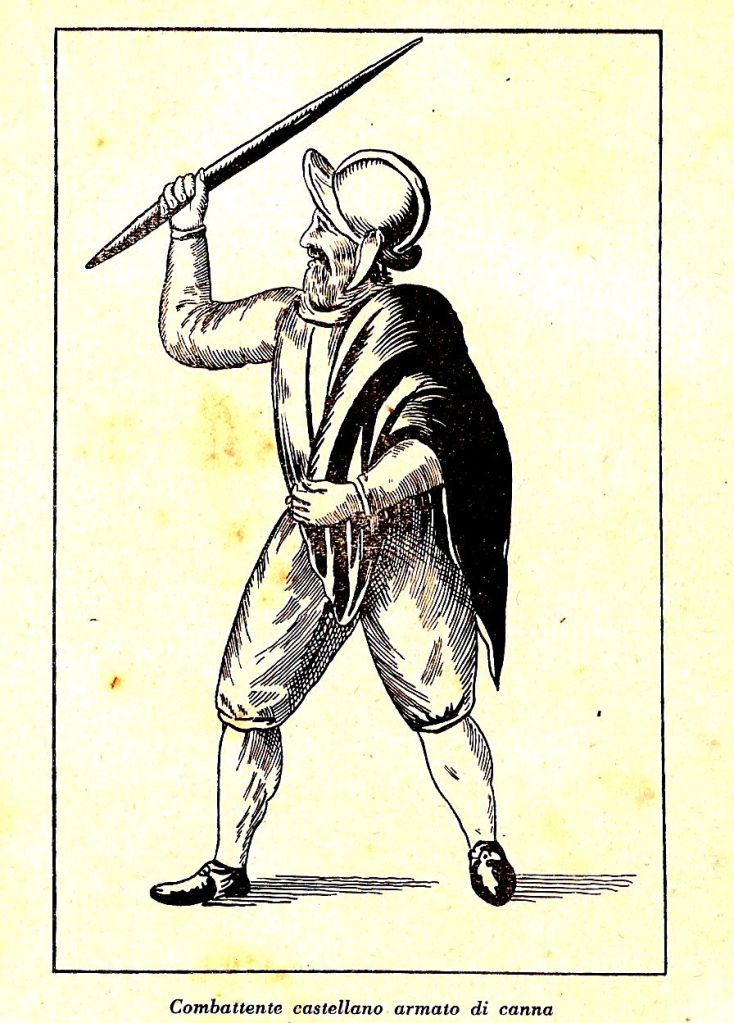

The end result also does not fit. We know that French La Canne was inspired by sabre fencing, and both are very similar, and so if Irish stick came from the same source it would probably also be quite similar, but then we have absolutely no source that mentions an Irish style which would resemble sabre fencing. In fact, certain sources such as Allanson-Win or the San Francisco Call’s Article are very clear in differentiating bataireacht from contemporary fencing.

Leboucher’s manual on French cane (1843) is quite close to sabre, while Bataireacht is not

What is much more interesting is to observe that clubs were once extremely popular weapons all over Europe, at least until the 18th century. The imagery of similar clubs is found in Ancient Roman mosaics, medieval illuminated manuscripts and even the art of William Hogarth. But by the 19th century, only the Irish and Britons still used them, the later abandoning them rather early. Would this be indicative that the shillelagh would, in fact, be the remnant of an ancient type of vernacular martial art that survived on the Island as other European traditions such as the bagpipe did?

The gladiator mosaic at the Roman villa in Nennig, Germany (100-200 AD)

Ireland before the mid 17th century is very little documented. Beyond the Pale (the region around Dublin) the British had little power and few foreigners dared to explore it. The few who did so painted a picture not unlike the first explorers of America. Ireland at this time was perceived as the New World in some people’s eyes, and many chroniclers referred to the Irish as “savages”. It is then very hard to get an image of how the Irish used their weapons or even what kind of weapons they carried. Fortunately, we do have some clues.

The way in which the shillelagh itself is handled in combat is quite unique in today’s world of martial arts but is again not unheard of in European history. The few references we have of Venetian stick fighting from the 16th and 17th century shows, at least, a very similar guard, Hungarian traditional dances imitating stick fighting also exhibit a similar third or, at least, middle grip.

The guard of this Venetian bridge fighter is very close to Irish stick.

Basic elements of this grip are also found in Ireland as early as the 12th century. Gerald of Wales says of the Irish that they carry axes –borrowed from Norwegians and Ostmen- as others carry walking sticks and that they grab these axes one-handed (one would guess around the middle to avoid making such a forward weighted weapon as long as a walking stick totally unwieldy).[2]

Thomas Gainsford in The Glory of England had this to say of the Irish warriors:

“The men wear trousers, mantle, and a cap of steel; they are curious about their horses tending to witchcraft; they have no saddles, but strangely fashioned pads, their horses are for the most part unshod behind: they use axes, staves, broadswords, and darts.”[3]

But possibly the earliest reference to shillelaghs can be found in the Ulster Cycle’s mythological tale The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel. The owner of the hostel had a sword but his warriors were described as such:

“Thereafter Da Derga came to them, with thrice fifty warriors, each of them having a long head of hair to the hollow of his polls, and a short cloak to their buttocks. Speckled-green drawers they wore, and in their hands were thrice fifty great clubs of thorn with bands of iron.”[4]

Club wielding saint in St. Canice’s Cathedral Kilkenny, tomb of James Schortals and Katherine Whyte (1509)

And so we can see that the Irish were already using something very close to shillelaghs. It is then much more probable that the shillelagh was always a weapon used by the Irish and European working classes, which became closely associated with Ireland as other countries abandoned it and that faction fights started to attract the attention of chroniclers.

2. The Faction Fight

“Ireland glory and her shame – the great fair of the country, the annual revel so celebrated in song and story, the unapproachable and unequaled Donnybrook Fair…”

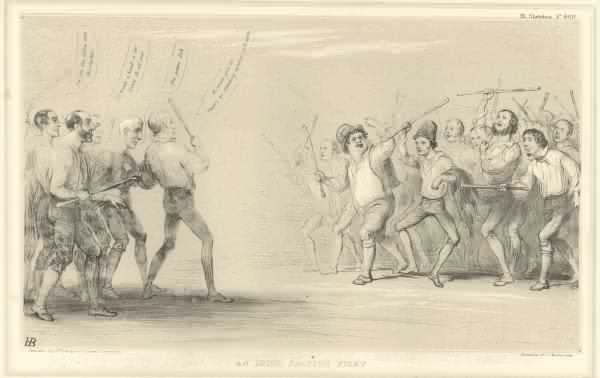

A caricature from John Doyle in 1846. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s grandfather was born in Dublin in 1797 and many of his caricatures depicting faction fights seem to show a good understanding of bataireacht.

It is through the practice of faction fighting that bataireacht will become known to us. Faction fight is a loose term describing the practice of fighting among groups of Irishmen throughout the late 18th century up until the early 20th. Two or more groups assembled to fight using mostly rocks and sticks, very often resulting in the death of many participants. Interestingly even though it caused death, the practice of faction fighting was considered good fun and in fact, people brought to justice for killing people in faction fights were often exonerated.[5] But not all of these fights were done with playful intent; in fact, many were done to settle feuds and political or religious tensions especially in the North. These were known as “party fights”, the biggest of its kind went on in Ballyveigh Strand in 1834:

It had been rumored that a faction fight was going to happen.

On 24th of June, 1834, on the occasion of the Ballyeagh strand

horse races on St. Johns Day, the Lawlors/Mulvihills encountered

the Cooleens. The battle was fought with special sticks called

Blackthorne sticks or cudgels. Some were weighted with lead

and were not used free swinging but were held in the middle to

protect the elbow. An estimated 1,200 of the Cooleens crossed

the Feale in boats from the north and were then in what was

considered Mulvihill/Lawlor territory and was in itself considered

provocative. They Cooleens attacked the Mulville/Lawlor people

who were generally imbibing with poteen and whiskey. The invaders

came forward in lines with about 20 women on the sides with aprons

full of stones. The authorities tried to stop them from coming but

were unsuccessful. At first the Cooleens got the upper hand since

half of their adversaries were still in their tents having a good time

with their whiskey. Gradually the Mulville/Lawlor faction got organized

and about 1,500 of them counter-attacked. They drove the invaders back

into the water and won the day.[6]

It is said that 2 to 300 men died on that day. The height of the Faction Fight era is considered to be in the decades preceding the Great Famine. Afterward, the practice will continue but with less fervor, with some of the last faction fights taking place in the 1880s. The practice of stick fighting was so closely associated with the fights that it too suffered from the disappearance of the practice; we shall examine later on the reasons behind this phenomenon.

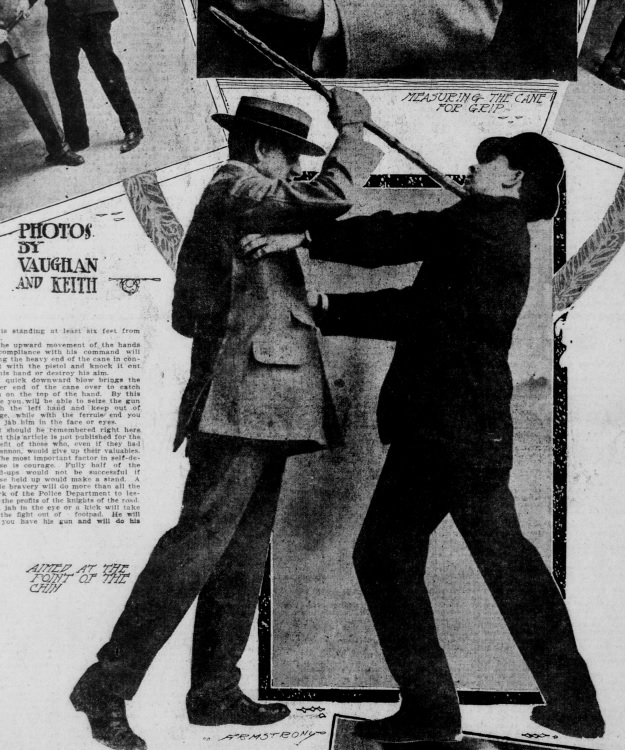

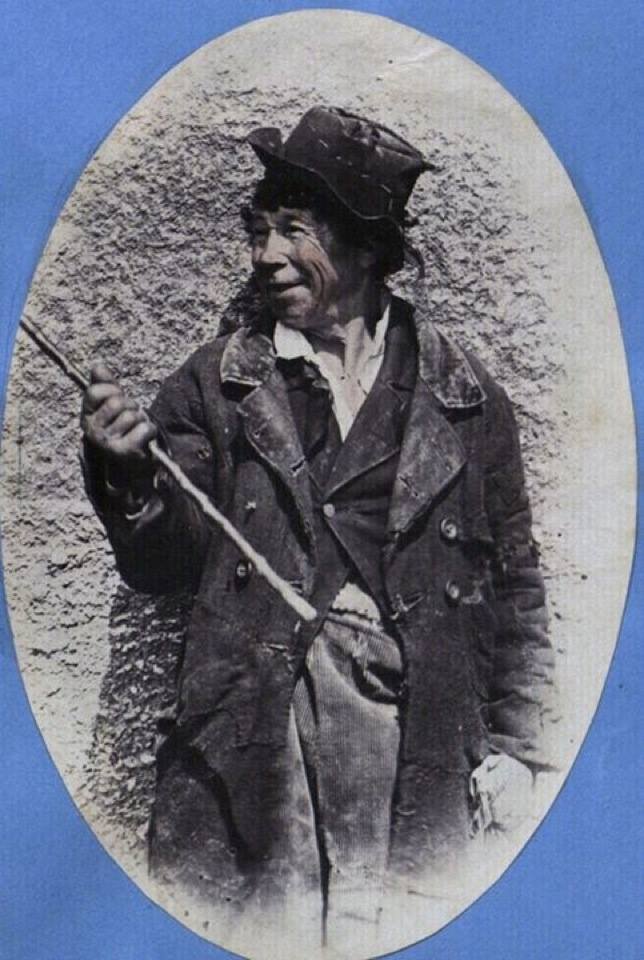

A rare picture of a faction fighter, possibly from the 1850’s

3. Masters, fighters and knights errant

It is easy to consider that Irish stick fighting was a crude affair that demanded very little skills from its participants. After all, it was a peasant art and peasants were rough and unrefined people with a very little understanding of the noble art of combat, and no time to even consider practicing it… Or were they?

In fact, when we look at European history, we can find many popular traditions of stick fighting which were separate from the trade of fencing masters or even of the warrior aristocracy. Norman, Breton, Bearn, Basque, Parisian, Sicilian, Venetian or Portuguese, all of these people and more had their own famous styles of vernacular stick fighting. France had since at least the 15th century the tradition of the “baton à deux bouts” or “two ended stick”[7], which was an art of its own with its particular masters until it was amalgamated in the military system of Joinville in the 19th century. The same was also known in Brittany where schools of stick fighting were known to exist and taught the use of the Penn Bazh as Parisian schools taught the use of the sword. The Irish were not so different in this regard; schools of stick fighting are recorded around the country, sometimes near places of important fairs such as Tipperary where faction fights regularly went on.

Professional teachers of the art seem to have been numerous. Down, apparently, to the first quarter of the last century, there was at Cahir, Co. Tipperary, a school for the teaching of stick-fencing, and the instance seems not to have been an isolated one. A choice selection of fencing-sticks used to be placed on a stand in the street opposite to this establishment. A grown male person handling one of these sticks through curiosity would be asked by a pupil of the school: “Are you able to use that stick?» and the answer being in the affirmative, battle was at once joined. Thus did the school advertise itself. Fathers of families used sedulously to teach the practice to their boys, the parent in such case being a modern representative of the military tutor of former times.[8]

A school is also said to have existed in Derry to train men before fairs[9] and the famous author William Carleton wrote how traveling dance masters would also often teach the use of the shillelagh[10]. Another one was recorded in County Kerry:

Tis eight score years ago there stood but one house in the Buailtin (the old Irish name for Ballyferriter, still used locally) at Ballyferriter. A Maighistir Prionnsa (fencing master) [note that while O’Donnell uses this curious version -prionnsa is usually not “fencing” but “prince”- the 1959 Bhaldraithe dictionary gives máistir pionsa as the Irish for “fencing master”] lived in it. The young men of the parish used to be coming to him every day, and he would teach them with a pair of sticks. The Fencing Master would have two sticks, and the learner the same (presumably long smooth sticks, like a dowel). He would train the learners to hold off every blow.[11]

Even though the practice of faction fighting was ridiculed in Britain as barbaric, the skill of the fighters themselves was highly praised. Certain references in the world of fencing such as Allanson-Winn even went so far as to say that skilled fighters could overcome a good fencer. “Sometimes a great deal of skill is displayed, and I often wonder whether a really expert swordsman would be much more than a match for some quick, strong, Kerry boys I could pick out.”[12] And certain of them did:

Old Donal McCarthy drank here also. The old man witnessed the Famine, its aftermath, the years of recovery and the shameful spectacle of faction fighting between cudgel-wielding clans. He too, among others, was expert in the use of the cudgel in self-defence. This art was the equivalent of the cut, thrust and parry of swordplay, as practiced in the naval sailing fleet of the time. The faction-fighting clans called this form of self defence Boiscín or “boskeen”. The so-called shillelagh took the place of the sword.

Irish shillelagh-wielders were known to have beaten some swordsmen.

Coastguard Tommy Adams suspected that old Donal was perhaps an expert in the use of the shillelagh as a weapon of self-defence and therefore wished to test the old man’s skill. Then came the day when the old man grew tired of Adam’s persistent challenging him to fight a duel with cudgels. At last, Donal accepted the challenge. The proprietor of the tavern, Paddy Haren, was appointed the referee. The winner was to be the contestant who first made bodily contact three times. He would receive a half bottle of ship’s rum, the loser a quart of ale. Each man was to have the approved shillelagh of equal design. A day was appointed and the floor of the tavern cleared of furniture. The bout itself was to be kept secret, in case the law would frown on such an activity.

Old McCarthy, divested of his jacket and homespun gansey, rolled up his sleeves and carefully pulled his stockings over the hem of his frieze trousers, before taking off his heavy brogues and stepping nimbly on his vamps. With Donal’s scant grey locks and beady blue eyes, he performed a short ritual dance, twirling his shillelagh like some Zulu warrior. The coastguard explained very sincerely to the old man that he only wanted to ascertain the truth of whether the Irish stick-wielders were skilled in the art of fencing. McCarthy replied, “B’fhearr dhuit ciall a bheith agat”, meaning “Better for you to be sensible”.

Paddy Haren who was also a swordsman bringing the two unequal protagonists together, advised them to show their skill in imitating sword play and, drawing a line on the floor, he called the word, “Advance!” following in raised voice, “On guard”, then the final word “Go.”

Old Donal danced like a paper doll and it was soon evident that he was under pressure from a very skilled adversary, a product of naval training. As yet an opening for a touch had not presented itself. Old McCarthy was backed into a corner. Then it happened: the knob of Donal’s shillelagh made contact over the left ear. Tommy Adams winced under the sudden stinging impact, only to receive two more resounding taps in quick succession, directly in line over the left ear.

Paddy Haren stepped in, declaring the contest over. Adams shook the old man’s hand, who remarked, “Na duirt mé leat ciall a bheith agat.” Meaning, “I told you to have sense.” Three lumps like thrush’s eggs began to grow over Tommy’s ear, to which he applied cold water. This convinced him that cudgel fighting and fencing derived from the same art. The above account I heard from my cousin, old John Fitzgerald of Horse Island.[13]

Good stick fighters could also acquire quite a reputation, often becoming the champions of their respective factions. Fighters looking to build their own fame would go along the country looking for worthy opponents in a way which reminds us of Japanese tales of wandering samurai.

Paidin Gearr: (Related by the late James O’Flynn, Fethard, Co. Tipperary, formerly of Lisronagh, Clonmel-born in I843).

Three miles N. N. West of Clonmel, near where on Giant’s Grave Ridge, a great pillar-stone keeps its multi-millennial watch over the North-Decian frontier, lived in the early part of the last century Patrick Connors (O’Connor), a shebeen-keeper, nick named from his diminutive stature, Paidin Gearr, who was the acknowledged champion stick-fencer of the country-side, and whose small stature gave emphasis to his victories over bigger men. Paidin had a contemporary near Killenaule, a man of great physique, whom the writer will call K-. This man was the leading champion of the Thurles region, and his neighbours, jealous of Paidin’s spreading fame, and anxious for the glory of their locality, prevailed on K- to seek out Paidin and fight him.

One fine summer morning, K- set out on his quest, essentially a modern knight-errant. Near Giant’s-Grave, after a stiff journey of ten Irish miles, he came upon a diminutive man digging manure by the roadside, and after salutations, K- asked the digger to direct him to Paidin Gearr. The digger, shouldered his spade, took K- to a shebeen, and called for two naggins of whiskey. In those days the naggin was a man’s drink, and subdivisions of that measure were left to women and youths. When the naggins were finished, K- asked to be directed to Paidin Gearr. Said the diminutive one: ” What do you want of Paidin Gearr ? ” “To fight him,” quoth K-. “I am so-and-so from Killenaule.” Said the diminutive one: “I am Paidin Gearr! “

Turning aside, he produced a bundle of choice fencing sticks, and bade K- take his choice. K- was delighted, for owing to the small stature of his prospective opponent he promised himself an easy victory, and he wanted to fight at once-but Paidin flatly refused. “I will not fight,” said he, ” unless there are two men to stand with’ us–one with each of us-to insist on fair play, and to save the beaten man. And we must fight early in the morning when nobody is about, for otherwise, if you beat me, you will not go home alive. Rest here to-night, and we shall fight early in the morning, and the two Barrys of Rathronan will stand with us.”

The details of the encounter have not survived, but K- was beaten. The resulting spree lasted three days, and K- returned home, defeated, but not dishonoured, and a firm friend to his diminutive antagonist.[14]

Work in the past was not always as time-consuming as we imagine it today. In Ireland, many of the stick fighters were involved in the harvesting of potatoes. The harvesting season was quite short and little had to be done afterward.[15] The situation of peasants in the Middle Ages was not so different; in 14th century England, for example, peasants would work 150 days a year.[16] This left a large amount of time to practice stick fighting if one desired to. And while stick fighting and fencing can be quite close, they also ask for very different skill sets and body mechanics. It is then easy to understand why those peasants gathered such a reputation as formidable fighters: they had the time and motivation to train and did not have to develop a system which had to fit in a certain frame.

4. Women fighters

Rose Galh avenging her husband’s death

Was bataireacht exclusively a male occupation? In mainstream Irish culture of the time, it would appear so. But women were not relegated to the passive role of observers (or victims). Many would stand on the sides of a fight, holding a handkerchief filled with rocks to use as a flail and assisting their family members during a fight. While a man could parry a woman’s blow it was seen as taboo to hit her with a stick.

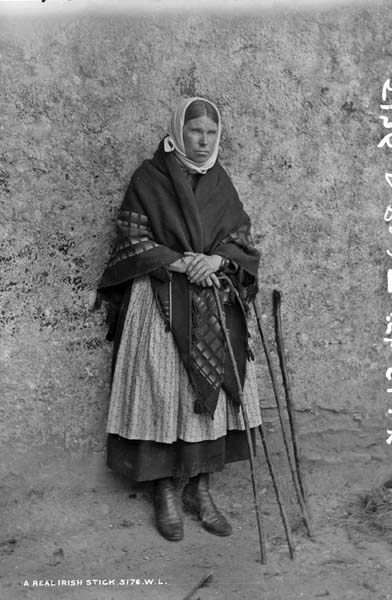

An Irish woman selling shillelaghs

The Travelers (Irish Gypsies) community had a different view on the subject, and it seems that women were free to join fights with a stick. some of them such as Mary Maughan or “Mary the stick” managed to acquire quite a reputation as fearsome faction fighters. This was quite shocking for many non-Travelers ( American Outsider: Stories from the Irish Travelers Diaspora, Cambridge, 2007).

5. The stick itself

A shillelagh maker gathering blackthorns

Various names were used to describe the Irish stick in Gaelic depending on the time and region, but the most famous name today is probably “shillelagh” which seemed to describe mostly the three feet long version. The origin of the name has been quite debated for years.

The barony of Shillelagh was famous for its oak forests which were used from the 17th century and up to create sailing ships and even the structure of the roofs of Trinity College library and Westminster Hall. The quality of its oak cudgel was supposedly such that the word “shillelagh” by antonomasia became synonymous with the Irish stick, regardless of its material. Oak was of course used but also holly, crab-apple, ash and, of course, the most famous of all: blackthorn or baathascor.

Blackthorn, or sloe, is a shrub from the prunus family which was at some point extremely common in Ireland. The tree grows and reproduces very fast and was often used in place of cattle barriers. It also has the added bonus of being one of the woods which has the best solidity to lightness ratio, making it very useful as a material for fighting sticks.

The root knob is kept on most sticks to make the striking part of the weapon. It was often filled with lead to make it even deadlier. I have examined personally two types of antique loaded sticks. The first one is in my collection and the presence of lead can hardly be noticed as it was effectively hidden inside the knob. The other one, unfortunately, was bought by someone else before I could acquire it, but it was a very slender stick with a knob on which every aperture had been covered with lead, making it very apparent.

On some antique blackthorns, you will find the thorns still in place. It is sometimes argued that they were used to deliver vicious blows, but it rather makes the wielding of the stick awkward and the use of the knob nearly impossible. It is rather more likely that these thorns denote the nature of the stick as being a simple walking stick, not intended primarily for use in a faction fight. Once cut down the vestigial thorns do act as a protection for your hand as strikes can be diverted or at least slowed by them.

This thorny stick, even though carried by an Irish-Canadian soldier in WW1, was clearly not meant for a faction fight.

By the late 19th century blackthorns became extremely popular with tourists visiting Ireland, so much so that local makers came to be short of blackthorns. They had to import it from America in order to sell them back to American tourists. As you might suspect not all antique shillelaghs were fighting sticks.

This infamous “shillelagh” pollutes tourists shops in Ireland and even abroad. The wood is painted black, the handle is very roughly shaped, the thorns are often glued and the ferrule is very cheap. This could be made out of any type of wood and if you are looking for an authentic shillelagh there are much better choices.

There were many ways of making a shillelagh, using sometimes butter to oil it and the fire of a chimney to cure it. But one method was described which probably is one of the most advanced ones.

The shillelagh was not a mere stick picked up for a few pence, or cut casually out of the common hedge. Like the Arab mare, it grew up to maturity under the fostering care of its owner, and in the hour of conflict it carried him to victory.

The shillelagh, like the poet, is born, not made ; though, like the poet, it is developed and polished. Like the poet, too, it is a choice plant, and its growth is slow.

Among ten thousand blackthorn shoots, perhaps not more than one is destined to become famous ; but one of the ten thousand appears of singular fitness among its gnarled companions. As soon as discovered it is marked and dedicated for future service. Everything that might hinder its well- balanced development is removed from its vicinity, and any offshoot likely to detract from the perfect growth of the main stem is skilfully cut off.

With constant care it grows thick and strong, and the bulbous root can be shaped into a handle which in an emergency can be used as a club.

Hugh Bronte was a man who looked before and hastened slowly. In early life he planted two oak trees by the edge of the Glen to supply wood for his coffin. They have become large trees, and they were pointed out to me by the nearest neighbour, Mr. Christopher Radcliffe, on the occasion of my last visit to the Bronte Glen.

Hugh had for many years been watching over the growth of a young blackthorn sapling, as if it had been an only child. It had arrived at maturity about the time the diabolical article appeared in the Quarterly, The supreme moment of his life had arrived, and the weapon on which he depended was ready.

Hugh Bronte returned home from the manse with his whole heart and soul set on avenging his niece. His first act was to dig up the blackthorn carefully, so that he might have enough of the thick root to form a lethal club. Having pruned it roughly, he placed the butt end in warm ashes night after night to season. Then when it had become sapless and hard he reduced it to its final dimensions. Afterwards he steeped it in brine, or ” put it in pickle/’ as the saying goes ; and when it had been a sufficient time in the salt water, he took it out and rubbed It with shamois and train oil for hours. Then came the final process. He shot a magpie, drained its blood into a cup, and with the lappered blood polished the blackthorn till it became glossy black with a mahogany tint.

The shillelagh was then a beautiful, tough, formidable weapon, and when tipped with an iron ferrule was quite ready for action. It became Hugh’s trusty companion, esteemed and loved for its use as well as for its beauty. No Sir Galahad ever valued his shield, or trusted his spear, as Hugh Bronte cherished and loved his shillelagh. [17]

The method described here shows a very advanced method of producing a fighting stick, one which was very much ahead of its time. The use of brine might sound strange to most people who have seen what salt water can do to wood, but we are talking here about a controlled submersion which acts the same way as a modern chemical treatment by flushing any remaining sap and replacing it with salt crystals which close down the wood’s pores. The same method was said to be applied to many fencing-sticks used to train sailors. The train oil (another term for whale oil) acts as a second barrier. Putting the knob in hot ashes also slowly transforms the wood fibres into carbon fibres. The stick is then dual hardened; the shaft stays more flexible to absorb parries and shocks while the top is harder resulting in more damaging blows.

6. Becoming infamous

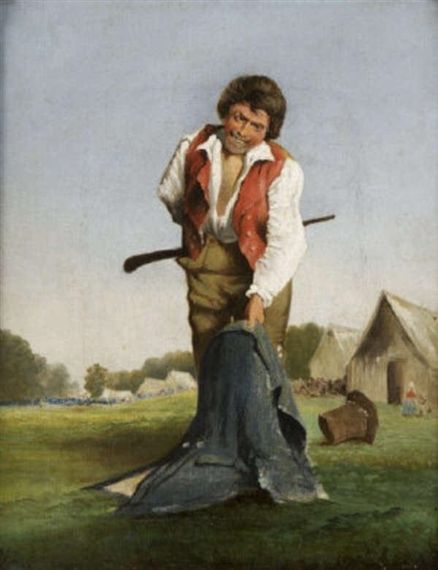

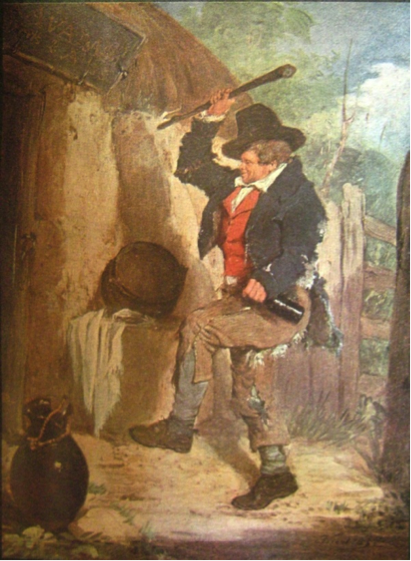

Donnybrook Fair- a call to fight by Erskine Nicol (around 1850). The fighter is dragging his coat, hoping that someone will step on it to initiate a fight. The expression “coat dragging” is still used today in Ireland to talk about someone who seeks trouble. Many are unaware of its origin.

So how did such an immensely popular art disappear to the point of being now virtually unknown to most people in its native country? Many factors contributed to the fall of boiscín, one of them was the disappearance of faction fights. Following the Great Famine, fights became rarer. Many fighters had left the island, others were dead, the Church began to criticize the violence and the British Crown- which previously decided to turn a blind eye on the practice- finally decided to change its stance on Faction fights and began implementing harsh sentences to those found guilty of participating in one.

Many faction fighters and fencing masters left for the New World

But perhaps the biggest threat to the survival of the art came from within. After the Famine nationalism went on the rise. Many people were blaming England for its conduct during this time and voices were being raised to unite against the British. Factions were seen as fractional, plotting Irish against each other, and so the Irish elite began to promote other activities.

The violence in Ireland was also used by British proponents of colonialism to argue that Ireland was not mature enough to go on its own, even making remarks as to the “racial inferiority” of the Irish. It also appears that to some authors, faction fights were a threat to the economy and a loss of productive time:

“Mr. Inglis looks upon it as most essential to the prosperity of Ireland that these factions should be put down. They are nearly as inimical to the investment of capital and nearly as much do they encourage absenteeism, as many of those other kinds of agitation which are more familiar to us.” [18]

Bright prospect by Erskine Nicol. Paintings such as this one were very popular and created a certain image of the Irish as a drunken brawler. A stereotype which the Irish people have long tried to defeat; making the promotion of a revival of bataireacht laborious.

One of the most effective ways to put an end to the tradition was the creation of the Gaelic Athletic Association. Founded mainly with the aim of counterbalancing the modern sports being imported from England such as football – which were becoming very popular- the GAA regrouped under its authority a series of sports which were also quite violent and reformed them so they would be pacified. The sports chosen were either invented (Gaelic football was invented by the GAA to compete with British football) or connected to a more “pure” Gaelic culture such as hurling which was mentioned in heroic tales. Ironically, rounders, another sport chosen by the GAA, was originally a British sport (perhaps unknown to the members of the GAA) which got included in the line up as it had become quite popular in Ireland over the centuries.[19]

It would have been possible to somehow reform Irish stick in order to make it a more peaceful sport such as Olympic fencing, but its association with faction fighting was too evident and it is possible that it was viewed by the GAA as a corruption of the British rule over Ireland’s culture. Faction fighters were encouraged to vent off during hurling matches, which at one point were often connected with faction fights; hurling games being a pretext to start a fight.

The Fighter by Daniel Macdonald 1844. Macdonald was an Irish painter from Cork, who is one of the rare artists to paint scenes of Irish life with a more engaged vibe. While artists like Nicol capitalized on the comical or fearful aspects of faction fighters to better sell their work to the London elite, MacDonald instilled some nobility in his fighter who is probably the captain of his faction. Of note is a rare depiction of a bugle player, possibly used to signal orders to the faction.

The GAA was very successful and surely helped to end the faction fights and nearly kill the practice of stick fighting. The faction fights were now looked upon with disdain and shame. Certain mentions of stick fighting are still made around the 1920s, and I have met people whose parents knew the art but didn’t pass it on, but by the 1910’s it seems that the tradition had completely moved underground and was rarely observed.

A couple of authors did try to raise the profile of Irish stick fighting but did so in a way that contributed to creating certain myths about the origin of bataireacht. For them stick fighting came from the noble art of sword fencing; it had been deformed and came to serve the purpose of fighting in between Irishmen. Ironically, the Irish noblemen of the medieval period were quite apt at fighting between themselves before the advent of faction fights. This view is often associated with traditionalism; which views peasant culture as a corruption of the aristocracy’s: peasants wished to imitate the nobility and in so doing deformed their noble pursuits. The same arguments were raised in the practice of Briton wrestling or Gouren. For many in the 1930s the Briton peasant had deformed the practice of wrestling and made it overly violent. The sportive reform was then making it closer to its original form, even though it was really a myth.[20]

The same approach was made with Irish stick. The theories were either that continental officers taught fencing to Irishmen whom they were recruited for service in France or Spain using sticks, or that the skill came from Irish fencing masters themselves. It was a way to redeem Irish stick: if it was an heir to a noble pursuit such as war, then it would be much more acceptable and perhaps could be “recivilized” in the same way as fencing or wrestling.

The same prejudice subsists today in Ireland, and it is not uncommon to hear Irish people being very dismissive of the art’s return, a reaction which is understandable given its absence in the public eye for more than a century and the fact that the resurgence has been mostly done in foreign countries where negative ideas about its practice are less of an issue.

While certain traditions such as music and songs were promoted as figureheads of Irish culture, the martial tradition of stick fighting was slowly forgotten (source: Sean Sexton Collection)

7. What does it look like?

It is probably impossible to tell how many different styles of bataireacht were around in the heyday of the factions, but thankfully a handful of traditions and documents were left for us to discover. Let’s look at them and try to see what they all have in common.

7.1. Traditional styles or Sean-nós

I will begin with the two known traditions that are still alive today. If one is interested in Irish stick I would, of course, suggest helping keep these traditions alive as much as possible. They present a sophisticated array of techniques which is unfortunately not found in the few historical documents that we have and represent a unique link to Ireland’s past. Like traditional Irish dance and music, I refer to them as Sean-nós or “old style”.

If you live in Ireland and have never encountered or heard about people practising the art, it is not a surprise. The resurgence of interest in the practice is relatively new and only a handful of people have kept their art alive (one that I am personally aware of) along with a certain culture of secrecy inherited from the days of the factions. If you do hear about someone who still knows how to use a shillelagh in the traditional manner please do tell me! Such unique knowledge must be preserved before it is lost.

Antrim Bata

The Antrim stick is as its name implies a style of stick fighting from County Antrim in Northern Ireland. The family tradition gets it back to the mid 19th century when a famous stick fighter from the region nicknamed “Tickety-boo” used it but it is possible that the style is, in fact, much older. The style was kept alive by the Ramsey family.

Tickety-boo supposedly used a four-foot staff, although the style has no preference for stick length, as far as it can be handled comfortably and quickly, and can even be as small as two feet. The main engaging guard is used in a fashion which is amply described in the historical sources, by holding the stick up one handed with the thumb extended on the stick and the lower part protecting the elbow. The use of the lower end in this manner is so common in Irish stick that it is mentioned in nearly every description of it, and O’Donnaill even gives us a name for it in his dictionary: cumhdaigh. The offhand protects the plexus and the ribs, and can be used to punch, grab or gouge.

It also has many points in common with broadsword fencing as practiced in Britain. The Scottish style described by Thomas Page in 1746 has many points in common, one of them being the way that power is generated through what Page calls “equilibrio” which is a rotation or the whole body in the direction of the attack. The guards used are also quite close to what was practiced all around Europe from the 17th to the 19th century.

The style is very brutal –as were many faction fights, especially in the North- and uses every weapon at the disposal of the fighter including slaps, gouges or kicks. Fighters grip the stick differently depending on the situation; two-handed in the middle when in close, one-handed when in a medium distance and grabbed two-handed by the end for dealing with multiple opponents.

For more information on Antrim Stick visit: www.irishstick.com

Rince an Bhata Uisce Bhata

The story of this style from the Doyle clan goes that it was developed in the 18th century by a member of the Doyle family who lived in Western Ireland and who was employed to protect clandestine whiskey distilleries. He would have modified a more classical style of bataireacht with boxing techniques to create his own take on the art.

It is known for its engaging guard which uses two hands flat in front with again quick punching strikes designed to open up the opponent to finish him in close.

7.2. Extinct styles

The elusive Troid da bhata or double sticks

A style which is often mentioned in historical sources is the Troid da Bhata (two stick fight) which used one stick in each hand; one short stick to parry and a longer one to strike. It is a curious combination, but unfortunately nothing else has transpired on the nature of this style and it is believed to have disappeared. The style was allegedly used by Walsh and Hally in Mount O’Dell and Paul Brien in Askeaton also fought with two sticks in the 1820’s; one called “death without a priest” and the other “down and out”. [21]

The style is also mentioned by Archibald MacGregor in his 1791’s Lecture on the Art of Defense.

O’Gallagher

The historian Marianna O’Gallagher (1929-2010) from Quebec City once told me that her father Dermot (1891-1977) from Macroom in County Cork knew how to fight with a shillelagh, a skill he had learned from his father Jeremiah. “He used a cane almost all his life, and he showed his son Dermot good form in “single sticking” – use of the cane, or his blackthorn stick for defence. He used his cane very jauntily.”[22]

Unfortunately he never taught his children the style, but he did talk to her a little bit about how it was done and – without ever having seen anything of what I or anyone else practice- she took up a stick by the third, thumb up and talked to me about how he would move the stick around so that it would mask his intentions. This concept is part of Antrim Bata where the fighter moves his stick continually. Unfortunately, the O’Gallagher style disappeared but the little which was shared helped to confirm our knowledge of the practice.

7.3. Documentary sources

Irish culture is in its nature an oral one. Although Ireland has produced great writers and manuscripts of great beauty, traditions such as stick fighting were always passed on by direct learning, not through manuals. That said, there are a couple of authors who – fortunately for us – have put to writing the techniques of their contemporaries. Several of them present only certain tricks and bits of info, but two of them are intricate enough to reconstruct a complete if somewhat simple style.

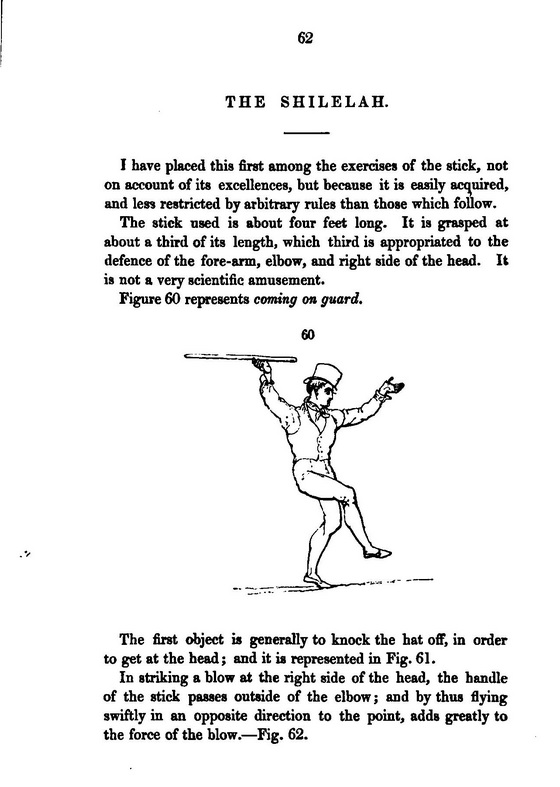

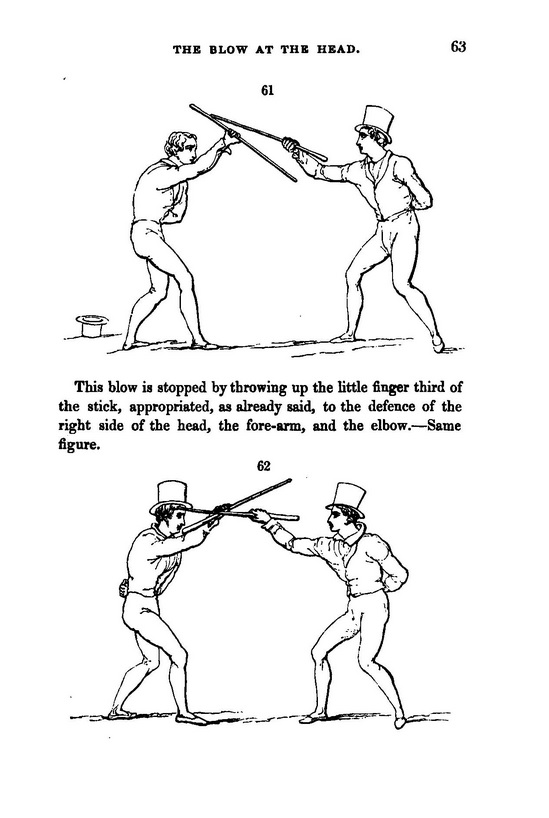

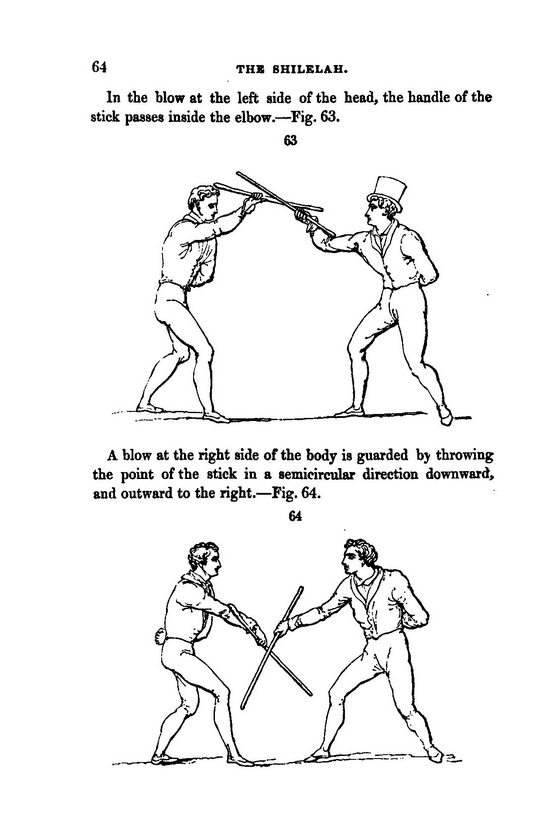

Donald Walker

Little is known of the author of Defensive exercises.[23] He is the first author to describe the use of Indian clubs in England in 1836 in his “Catalogue of British Manly Exercises” and is considered to have introduced gymnastics in Britain. It is unclear how he came to learn the shillelagh techniques he shows in his book, but he does not seem to regard them very highly. The style he shows is peculiar for its use of the lower end of the stick to do most parries with. Based on the description it is possible that Walker described some sort of game based on Irish stick and akin to singlestick. It is interestingly found in between the boxing and the singlestick sections. The strange position of the fighters off arm behind the back – which is never mentioned anywhere else – also seems to indicate that it might have been the author’s addition or again a specific kind of game. This is also supported by the fact that the fighters seem to hold their sticks knob down, possibly for safety concerns. I have here copied the entirety of Walker’s entry.

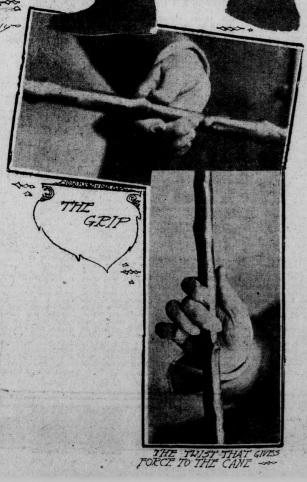

The San Fracisco Call’s “The Footpad and the Cane”

The San Francisco Call’s article of 1905 was discovered recently and proposes a method of walking stick defense based on bataireacht. The author notes that if many professors of walking stick defense base their method on fencing, he considers that the best method is rather to use the stick like the Irish. The details found in this article confirm many of the aspects taught in traditional boiscín – such as the use of the upper three fingers, the measure of the stick or the lowering into guard, but also introduce one very unfamiliar concept; that of fighting with the stick upside down. As mentioned previously, this is also part of Walker’s method and might be included as a safety precaution for friendly practice or bouts. It is possible that this choice was a hold out from the author’s practice, unknowingly included, or that he consciously included it taking into account the new legal concerns facing self-defense.

Others

Allanson-Winn described some techniques of “shillalah” in his book on broadsword, quarterstaff, and singlestick initially published in 1890.[24] Winn inherited a barony in Ireland and observed the practice of stick fighting. One of his most remarkable details is to mention the use of the backhand to protect the side of the head like a targe. It is not clear if the hand is to be left passively next to the head, or close to it to block.

This illustration from Allanson Winn is showing a stick fighter in between actions and shares a few points in common with Antrim Bata. The grip at the third, thumb up, over the head. It is unfortunately not very clear what Winn wanted to show in this instance.

Percy Longhurst, a student of Bartitsu, also gives us a couple of tricks for using a blackthorn stick with the usual Irish grip in 1918.[25] One of them, the blow on the forearm or elbow is often repeated in newspapers articles of the time.

Finally, a new source was recently discovered which might – or might not be- of Irish origins but is quite close in many respects. I will publish here one picture from this article which shall be presented in my next article.

Jafsie’s method

Another source, this time a video, was discovered recently. Click here for an analysis and comparaison to Antrim Bata.

8. How is it unique?

What makes Irish stick fighting so different from other styles? Let’s examine the case of Antrim Bata.

Most martial arts using short or medium sticks grab their weapons one or two handed but mostly by the extreme end, giving them superior reach. But this also comes with a handicap; The centre of balance being so far from the hand and the instrument being longer it needs a bigger movement in order to reach a speed high enough to do damage; even more so if the knob is being held at the top. Several ways have been devised in order to do so, either by bringing the stick to the back and striking back and forth as in Escrima or in circling motions such as in La Canne.

The high guard in Antrim Bata. Cork 2007

In Antrim Bata the stick is grabbed differently. The mass being even more forward than in most sticks it needs to be held higher in order to stay manoeuvrable. The lower third of the stick also acts as a counterweight or a pendulum; as the stick is thrown forward, the lower end goes backwards, giving added energy to the strike. It is then possible to use the stick in a much smaller motion, negating the need to telegraph the motion.

This grip also allows the fighter to use a guard which is unknown to most weapons art. If the stick was held by the end, the fighter wanting to take a high guard would essentially open up his arm as a target. As a consequence of this, the stick needs to be held lower, and only brought back to power a strike. In our case, the lower arm is protected as well as the whole front side. The only target that remains is the hand which can be protected quite simply while the stick is ready to strike at any moment. The high guard combines then both the advantages of a defensive and offensive guard.

This grip also means that the stick can be used quickly in a variety of distances. A long range can be covered by grabbing the stick by the end with both hands, which is mostly done to keep several enemies at bay, but it can also be used at medium and close range and even in enclosed spaces.

Parries are also much more secure as the lower part acts as a fail-safe in case that the target of the adversary’s blow is misjudged. If the stick was grabbed by the end the blow would go over or under it, but with the lower part sticking down one can still stay protected.

A short stick offers a strong parry anywhere on its surface, but covers less of an area. It is easier for the opponent to get an opening to strike.

A longer stick such as a cane covers a lot but it also offers a weak resistance on the upper half due to the length. A powerful blow could make this parry collapse.

The Irish grip combines the advantages of the short and long stick. Its parries are strong even near the tips and if used properly it covers a large area.

Finally, the stick can be grabbed in an instant from a normal walking stick position. A trained fighter can take up his guard in a second by sliding the stick up and instantly deal lightning-quick strikes.

9. Looking on to the future

We hope that this small overview has informed you better about the nature of Irish stick fighting and the tradition which are connected to it. Boiscín is now disconnected from the practice of faction fights and the students wishing to learn it are now much more interested in learning about this cultural heritage as well as using it as a means to self-improvement and self-defense. Hopefully, the art will one day take a seat among the celebrated cultural heritage of Ireland as the unique and rich practice it represents.

References:

[1] Bowdler, N. (2011, May 11). Early Bronze Age battle site found on German river bank. Retrieved January 28, 2015, from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-13469861

[2] Cambrensis, Giraldus. The Topography of Ireland. Trans: Thomas Wright, Cambridge: In Parentheses Publications.

[3] Gainsford, Thomas. (1620). The glory of England, or, A true description of many excellent prerogatiues, whereby she triumpheth ouer all the nations. London.

[4] Elliot, C. (Ed.). (1910). The Harvard Classics, Epic and Saga: Beowulf, The Song of Roland, The Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel, The Story of the Volsungs, and Niblungs (Vol. 49). New York: Collier & son.

[5] Conley, C. (1999). The agreeable recreation of fighting. Journal of Social History, 33(1), 57-72.

[6] SHANAVEST AND CARAVAT. (n.d.). Retrieved January 24, 2015, from http://www.ceolas.org/cgi-bin/ht2/ht2-fc2/file=/tunes/fc2/fc.html&style=&refer=&abstract=&ftpstyle=&grab=&linemode=&max=250&isindex=John’s Irish Air&submit=Search

[7] Académie de Vaucluse. Mémoires de l’Académie de Vaucluse (1882). 1890.

[8] Lyons, P. (1943). Stick-Fencing. Béaloideas, 269-272.

[9] Phelan, M. (2010). The advent of modern Irish drama and the abjection of peasant popular culture: folklore, fairs and faction fighting. Kritika Kultura, 15, 149-169.

[10] Carleton, W. (1830). TRAITS AND STORIES OF THE IRISH PEASANTRY.

[11] O’Donnell, P. (1975). The Faction fighters of the 19th century. Anvil Books.

[12] Allanson-Winn, R., & Phillips-Wooley, C. (1911). BROAD-SWORD AND SINGLE-STICK WITH CHAPTERS ON QUARTER-STAFF, BAYONET, CUDGEL SHILLALAH, WALKING-STICK, UMBRELLA,and other Weapons of Self- Defence. London: G. BELL & SONS.

[13] Kirby, M. (2003). Skelligs Calling. Dublin: The Lilliput Press.

[14] Lyons, P. (1943). Stick-Fencing. Béaloideas, 269-272.

[15] Phelan, M. (2010). The advent of modern Irish drama and the abjection of peasant popular culture: folklore, fairs and faction fighting. Kritika Kultura, 15, 149-169.

[16] Schor, J. (1957). The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure.

[17] Wright, W. (1844). The Brontës in Ireland.

[18] Irish Faction-Fight. (1842, January 1). The Journal of Civilization; Its Necessities, Progress and Blessings, 61-61.

[19] STOREY, David. “Heritage, Culture and Identity: The case of the Gaelic games. “ Sport, history and heritage: Studies in public representation. Ed. Jeffrey Hill. Boydell & Brewer Group, New York, 2014.

[20] EPRON, Aurélie. Histoire du gouren (XIXe-XXIe siècles) : L’invention de la lutte bretonne. Université Européenne de Bretagne, Phd. dissertation, 2008.

[21] O’Donnell, P. (1975). The Faction fighters of the 19th century. Anvil Books.

[22] O’Gallagher, M. (2008, January 1). Marianna O’Gallagher. Retrieved January 29, 2015, from http://irelandmonumentvancouver.com/side-3-the-100-names/the-100-names/marianna-ogallagher/

[23] Walker, D. (1840). Defensive exercises; comprising wrestling, boxing, &c. London: Thomas Hurst.

[24] Allanson-Winn. Op. Cit.

[25] Longhurst, P. (1906). Jiu Jitsu and Other Methods of Self Defense.

Reblogged this on Paleotool's Weblog and commented:

Nothing like a good piece of wood when you’re in a tight spot. Working in remote places with a bad dog problem, a walking stick or staff can be quite a comfort. You can carry one without looking (too much) like a thug even.

Reblogged this on Latosa Concepts, Filipino Martial Arts and commented:

A little inspiration from the european side of the block. Enjoy!

Reblogged this on Civilian Combatives.

as an old borderfien in wales and long time jujtsu budoka with long time interest in pressure points and originally taught by my father.when i was in the north. His ,father had a collection of shelaghilies ebony canes and truncheons,.knob kerries and walking sticks lately i’ve been practicing walking stick defence & made a buffalo crooked old broken bokken which although heavy;i find it natural to hold it in the Anterrim position as 4ft; plus long.

Having trained with a visiting martial artist from Cork@ a Professor Rick Clark seminar where we practiced escrima ;I wish we,d practiced Irish stick.

Hi I teach the Doyle style of Bataireacht here in the UK, I run a club in Buckinghamshire check us out at http://www.irishstickfightinguk.com

Reblogged this on The Obsession Engine and commented:

More on the fine art of cracking heads with sticks!

Lovely article.

Name of author and how to contact?

Hello Mr. Higgins,

I am the author, Maxime Chouinard. You can contact me at Maxdchouinard@gmail.com

Very nice article. It had many details I’d not come across. I learned a bit from Glen Doyle several years ago and have kept up my practice.

I am a senior Tai Chi teacher in Kitchener, Canada. One fact of interest is that both the Doyle family stick method and Tai Chi Yang family method break down the combative encounter into the same 5 stages:

Say Hello (Metal)

Rush In (Water)

Pivotal (Wood)

Cauldron (Fire)

Fury (Earth)

Does the Antrim system share this?

Nice piece hope to see more

Interesting. we do not have this concept in Antrim stick. There are different tactics and strategies depending on the context : who you are fencing, number of attackers, distance, weapons involved, etc. So there is no prescribed scenario, you only learn to apply different strategies by training and forging your own style of fighting.

You mention in the article problems with the theory that there was a style based upon sabre. The Cateran Society claims a Scottish source for their cudgel play. https://cateransociety.wordpress.com/?s=cudgel I practice Tai Chi sabre and all this looks quite familiar. I’ve experimented with use of the bata using sabre method and the translation is quite instinctive. In a vid of their single-stick they (Cateran Society) reference Celtic bata.

Actually, what I say on this is: “La Canne was inspired by saber fencing, and both are very similar, and so if Irish stick came from the same source it would probably also be similar, but then we have absolutely no source that mentions an Irish style which would resemble saber fencing”

There are a few fencing manuals which develop on using sabre/broadsword methods with a walking stick, such as the French La Canne one shown in this article. They are perfectly adequate methods of stick fighting and I practice some of them myself, but as far as we have observed the Irish had a very different way of using the shillelagh and I haven’t found any method that truly resemble fencing with a sword.

Thanks!

Absolutely fascinating. I have studied escrima and have dabbled with some Chinese and Japanese bo staff techniques, but never knew about the Irish fighting style. A pity that no such school exists in Michigan, because it would be quite good to learn. I will be looking for more on this style.

The rulers tried to outlaw carrying these Thorn sticks, but the judge over ruled it, saying he couldn’t outlaw canes.A skilled fighter could take down multiple attackers in seconds.They were designed to be dense enough to knock someone out with a tap on the noggin, and often “Loaded,” with some lead filling the knob..Hawthorn is another classic wood used for Irish stick fighting.Dense and thorny like Blackthorn.

There was actually a taboo on Hawthorne, which is why even though it is close to blackthorn in many ways you barely never see it mentioned. Hawthorne is very much associated with the fairies, and cutting some of those trees is very badluck. It was also considered that Jesus’s crown of thorns was made of hawthorn and that it would be sacrilegious to use the tree, even more so for a weapon I would guess. Those feelings have now changed, and you see people using this type of wood.

Just came across this, as I was remembering my oul lad telling me about his Da using a cudgel. It would be great to take this up.. though I don’t see any clubs in Belfast/Antrim etc

About the illustration from Allanson Winn is showing a stick fighter in between actions and shares a few points in common with Antrim Bata. The grip at the third, thumb up, over the head. It is unfortunately not very clear what Winn wanted to show in this instance. Is it a parrying illustration?

Here is a quote that may provide a clue “ ….. It is held somewhere about eight inches or so from the centre, and my countrymen, who are always pretty active on their pins when fighting, use their left forearms to protect the left side of their heads.” – Rowland George Allanson-Winn, quoted from The Victorian Gentleman’s Self-Defense Toolkit

Thank you for this wonderful article!