by Maxime Chouinard

To most people, punching seems like one of the most natural ways of fighting when unarmed. Most movies will show protagonists and villains alike dealing numerous punches, and knocking out minions with ease; sometimes with a single punch. Many modern martial arts involve punching to some extent. We seldom see street fighting footage that does not contain some of it. It might seem that punching is intrinsic to human fighting. One could assume it was always known and used. Maybe it appears innate to our nature as bipedal human beings.

In the recent past, a few academic articles even made some bold theories on human evolution. They suggest it was influenced by punching. These theories were made without first establishing if punching was really that common with our early ancestors. Here again, it is simply taken for granted.

Researchers who studied historical treatises and manuals dealing with unarmed fighting techniques soon realize this. Punches are actually quite a rarity in historical manuals. This is even more evident when looking for straight punches to the head. These techniques seem to appear with the advent of English boxing from the 18th century on. Why is that so?

I began writing this article a few years ago. I did not expect how much of a rabbit hole this question would be. In this article, I will present insights from historical sources which tell us about the presence or absence of straight punches to the head in fighting techniques of the past. I will also talk about the surprisingly misunderstood nature of a bare knuckle punch. I will explain how it became so common in modern martial arts, and hopefully present an explanation for it being such a historical oddity.

*Note that when I refer to “straight punches to the head”, I mean here the use of the front part of the knuckles, or MCP joints, to hit an opponent somewhere on their head. In the interest of lightening the text, consider that mentions of “straight punches” are meant to refer to them, and not those aimed at other targets.

Where do we find punching in historical sources?

One of the earliest known representations of what we would consider to be punches are found in the Ancient world. Some of the oldest representations that are believed to illustrate boxing were found in modern day Iraq. These plaques date from around 2000 B.C.E. No description of this activity is given, and none is known to exist from that period, but it has been interpreted as boxing, because of the stance, and also in one case to the presence of what could be hand wraps.

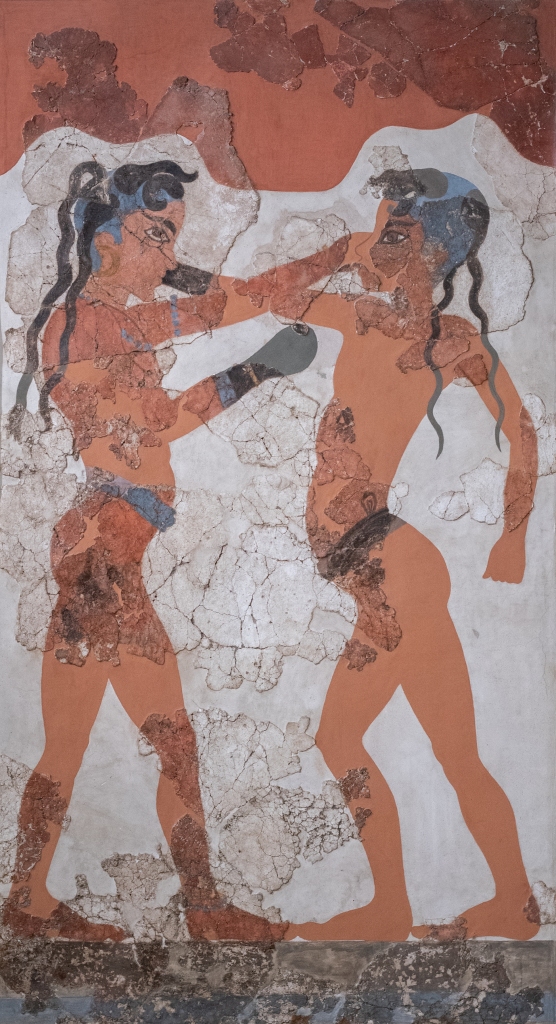

In the same era, we also find the famous Akrotiri Boxer Fresco, showing two Minoans, who are again probably exchanging punches. It is important to note though that this representation, as famous as it is, is also one of the most incomplete. What many ignore when looking at this image is that a vast amount of the fresco was reinterpreted by the people who restored it in the 1960s. It is then important to consider that what was represented may have been somewhat different than the original. For example, it is usually considered that the boxers are wearing gloves in one hand, and none in the other. Yet, looking at the actual fragments, the fighters may have worn some sort of glove. It could have also been some sort of a forearm band. We also have no idea what was or wasn’t on their other hand, as they are both missing.

Our modern minds associate such a posture with the end of a straight punch. It is also quite possible that it could illustrate hammer punches or even backhands. We also find similar stances in Egyptian funerary art.

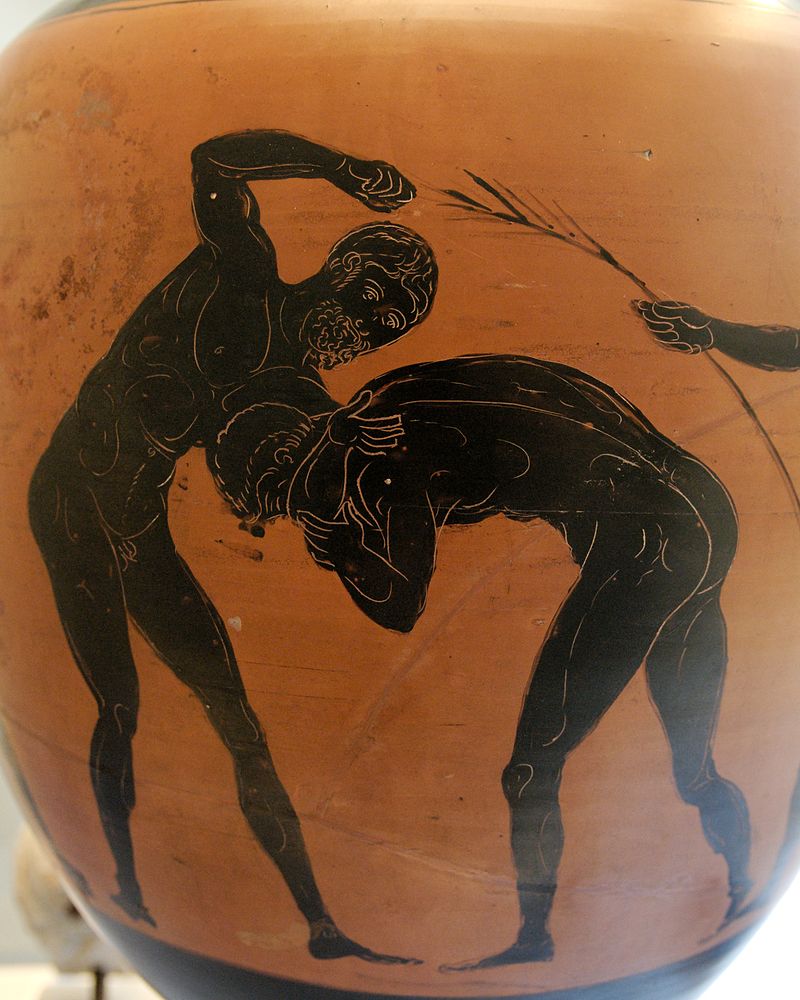

We only start to find actual information on the practice in Ancient Greece. This includes the practice of pygmacchia and its famous cousin pankration. We do not have very clear descriptions of techniques used in these games. However, we possess some elements that allow us to analyze its illustrations in pottery. We can also study fresco and statuary, as well as the actual equipment worn.

What we can establish is that there is no meaningful evidence that straight punches were used in Ancient Greece or even in the Roman world. The sources do not make any clear mention of this, nor do the various representations of the practice. We do see certain poses frequently rendered, including this very revealing one, with the fist raised up behind the head.

This pose will be seen through the medieval era up to at least the 19th century, and in most of these later cases is meant to represent a posture meant to deal hammer blows, which is to say the use of the bottom of the fist to deliver strikes. This manner of hitting is, as we will see later, infinitely safer for the person using it, and perhaps to the other fighter as well, as it is less likely to cause a concussion.

The hand protection used by these fighters is also quite interesting. What is popularly known as cestes are similar to some hand and arm wrapping in traditional combat sports. Examples of these sports are Muay Thai or Dembe. However, the protection they provide is quite different.

A cestus has a roll of leather strapping wrapped around the hand of the fighter. Its configuration would be quite alien to a modern boxer, as the protection it gives is very different to modern wraps, let alone gloves.

They rather appear to protect the knuckles and metacarpals from impacts coming at perpendicular angles, as would be the case with backhands or hammer strikes. We may then have to consider that these fighters perhaps did not use straight punches as our modern mind would expect them to. Instead, they relied on more circular strikes.

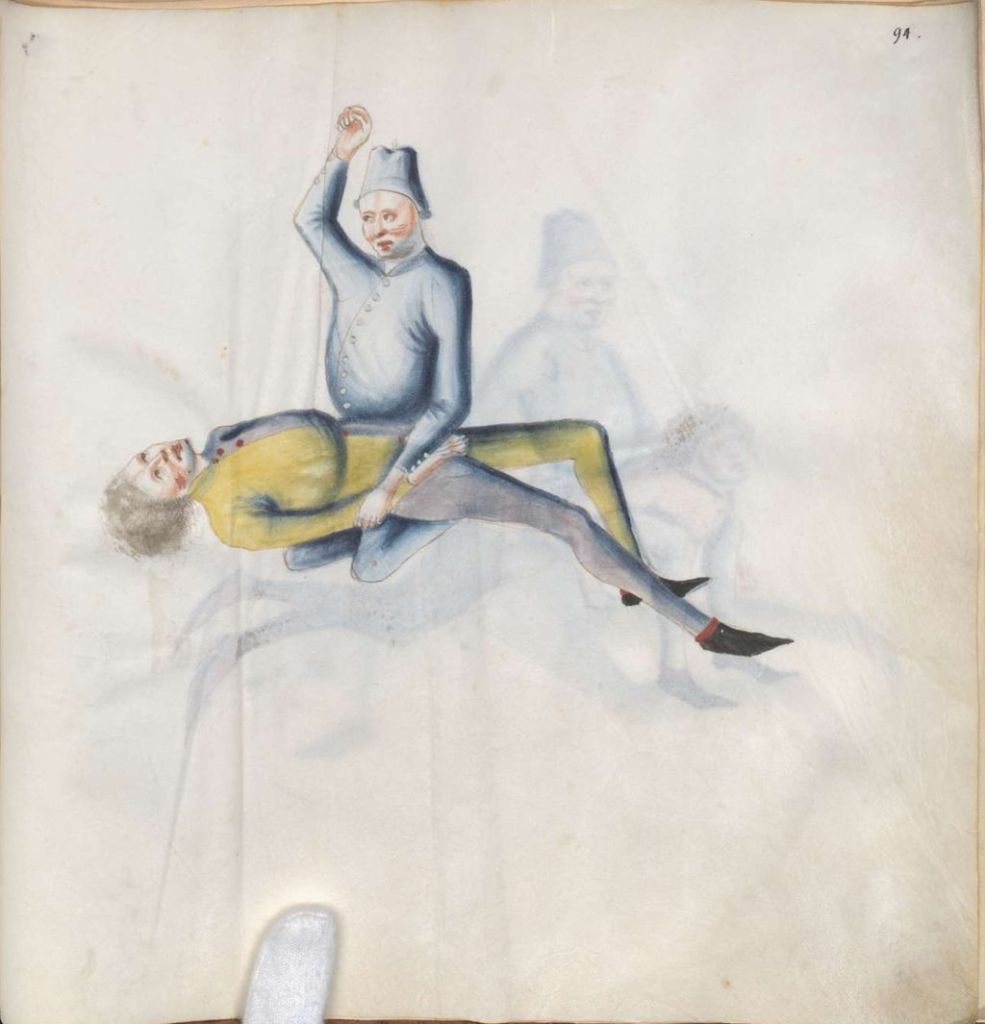

As we move into the Medieval era, we also start to see clearer descriptions of punches; this as soon as the 14th century. Fiore dei Liberi is one of the first Europeans to showcase such strikes in a martial arts treatise around 1409. The posture he shows will look instantly familiar to what was illustrated in Antiquity, and even later.

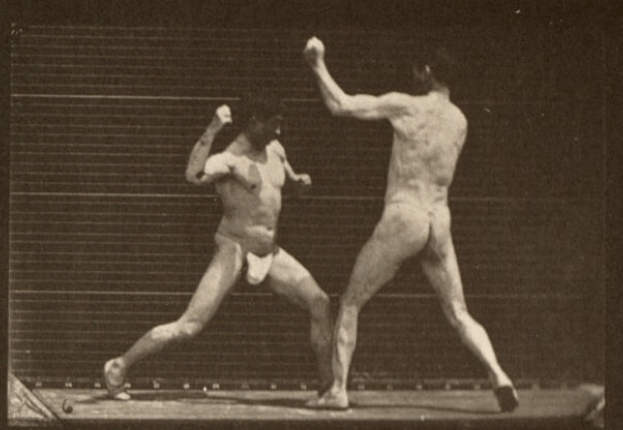

Photographs of two boxers from Edward Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion, published in 1887.

Most people today, if shown only Muybridge’s second image, would believe it illustrated some sort of uppercut to the body. However, it actually shows a hammer punch, called at the time a form of “chopper,” as it was likened to a cutting motion. These punches were fairly common in early British boxing up to the mid 19th century.

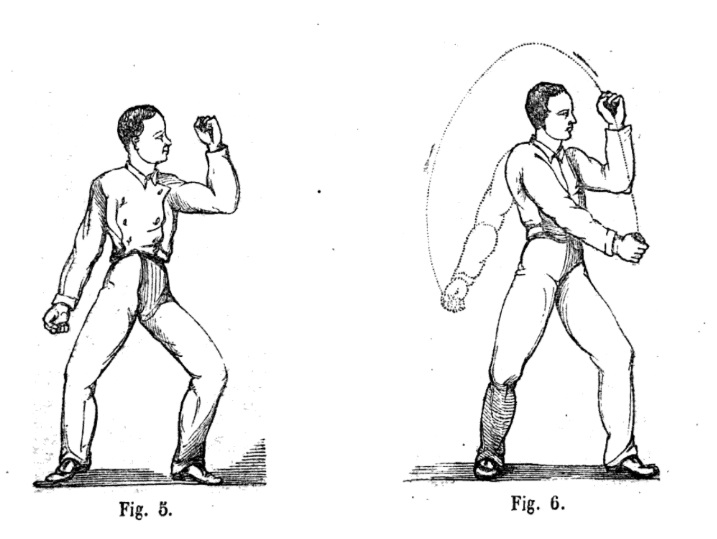

Illustrations from the 1875 Gymnastic manual of the French Navy, showing a fairly exaggerated hammer punch, at least compared to Muybridge

If these techniques were shown in their finality -meaning with a character receiving the blow- they may very well look the same to a modern viewer as a straight punch. We must then be very careful to consider our modern perception when examining artwork that is not accompanied by a clear technical description.

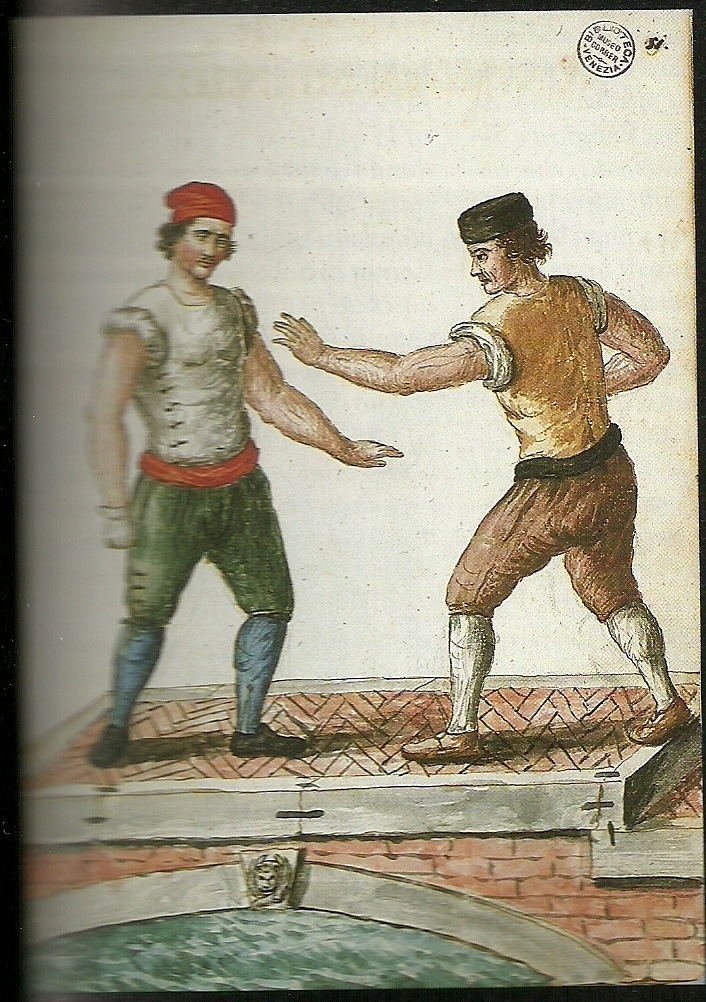

The Venetian Bridge Wars and the introduction of the straight punch

More than two centuries after Fiore published his treatise, a practice started to take place in the city of Venice which would eventually become an organized form of boxing; and perhaps one of the first clear documented use of straight punches to the face. Starting in the 14th century, factions would assemble on certain Venetian bridges to fight, usually with sticks. The goal being to knock opponents off the bridge. By the late 16th century, fighters started to abandon sticks in favor of their fists, and even introduced singular combats between two opponents called “mostra”. In these fights, two opponents would meet on the bridge, and seek to either draw a bloody mustache from their adversary’s nose, or to have them fall off the bridge. The Venetians” skill in punching became somewhat of a sensation in Italy, and even gave rise to confrontations with inhabitants of other cities, who wished to see for themselves how they would fare against opponents not trained in their methods.

For example, this excerpt describes the outcome of a fight between a group of Dalmatian mercenaries, and Venetian men in 1637.

Although these Slavs were accustomed to sorties and raids, to musket and harquebus fire, and to coming to the clinch with sharp steel, nevertheless battling with fists above a narrow bridge was much different from their training and courage, and therefore most of them were thrown down from the bridge into the water by the Nicolotto skill.

–Davis, Robert C. The War of the Fists: Popular Culture and Public Violence in Late Renaissance Venice. 1986, p.53

The same experience was repeated in 1670 when a battagliola was staged in Bologna as part of the celebrations for San Bartalomeo’s Day. Local Venetian expatriates were asked to fight a group of Bolognese and Ferrarese men for the occasion. The result was similar, but brought some more details to light.

Who with hostility were only waiting to give pitiless punches to the Bolognese, who did not even know how to throw a punch in the manner, I would say, of the Venetian battagliola, but rather they fought in the manner of the Dalmatians, who never lead with the point of the fist but only as if they were chopping wood with an axe. The Bolognese for the most part threw themselves voluntarily into the water, since they could not tolerate the violence of the Venetian fist.

–Ibid.

This skill aparently did not export itself to other parts of the region. Sailors coming up the Brenta were said to be as poor fighters, and only those of Bari proved to have some skill in this. The straight punch was considered so unique to the Venetians that many considered that they had quite simply invented it (Ibid). The Bolognese showed poorly. Even the fierce Dalmatian mercenaries performed insufficiently. This mounts a convincing case for the general lack of straight punching skills in Italy. This lack extends to most of Europe, even among soldiers.

Arguably the first instance of a straight punch in a European manual is given to us by Nicolaes Petter, a German wine merchant and wrestling master who took up residence in Amsterdam. Petter’s wrestling manual, published posthumously by his widow in 1674, was quite successful. The popularity of the book paired with its detailed engravings created a slew of wild conjectures on the origin of his skills resembling, at times, Japanese jujutsu.

Most of his techniques can, in fact, be traced back to earlier manuals, but his straight punch is quite an oddity. Where is this technique- never before presented in a manual- coming from? An influence from the already well established Venetian boxers, maybe in connection to his wine selling business? Venice was after all controlling a major trade route. Or maybe through the burgeoning sport of boxing in England, considering the close and tumultuous history between Britain and the Netherlands? Or some other obscure local tradition? The Venice and to some degree British connections can probably be ignored, as he is not exhibiting any form of guard common to these two practices at the time. Petter does mention in his text that the Dutch especially “punch each other on the chest and use the heavier fist punches later on during the fight”. He does show defenses against chest punches, including even double punches, but the technique above is the only one targeting the face. The way that the fists are closed in the illustrations does not seem to indicate techniques meant to hit the head with any meaningful force. The Venice and to some degree British connections can probably be ignored, as he is not exhibiting any form of guard common to these two practices at the time.

A Venetian trained fighter would probably have adopted this position instead, with the lead arm extended to possibly guard or control, and the back fist ready to strike.

As illustrated above when discussing ancient boxing, a question deserves to be asked: could we even be seeing a backhand instead of a straight? Petter, after all, does not give much indication as to the exact technique used. He simply describes it as a hit to the face.

A backhand punch from the French Navy’s 1875 Gymnastic manual. Inserted in Petter’s plate, it is almost indistinguishable and, to a modern observer, would look like a straight punch to the face.

This is may or may not be what Petter shows here, but we do have to consider that straight punches were absent in previous martial treatises, and continued to be so until the 19th century. If this was indeed a new technique, we could expect a little bit more explanation from the author. A backhand blow would be quite familiar to his readers, and so would constitute the simplest explanation as to which punch we are seeing here.

By comparison, Johan Georg Pascha, a prolific author publishing around the same era, includes very similar strikes as was seen in previous centuries. Choppers with the edge of the hand, and defense against what appears to be hammer punches. Pascha does include a novelty: an uppercut to the chin, which is the closest we get to a straight to the head for more than a century.

These battles will allegedly stop in 1705, after an event devolved into fights with knives and sticks, pushing the authorities to ban them entirely. This is somewhat contradicted by later events in London. The first international boxing match took place there in 1725. It was between John Whitacre and a Venetian Gondolier named “Stopa l’Aqua,” who was said to be quite a formidable fighter in his country. (Caledonian Mercury – Thursday 28 January 1725).

The British origin of modern boxing

The origins of boxing in England are poorly documented. We know that the practice exists in some form at least by the 1660s, where we read of the practice of cuffing or boxing, which seems to come from the English expression to “box on the ear”, which reffered to a punch or slap given, as the name implies, on the ear. The expression seems fairly old, being well present in the late 16th century even among aristocrats, and associated with punishments as well as fighting.

This, of course, leads us to the British sport of boxing. Prior to its appearance, punches are of course as common as in most parts of Europe, and in other games as well. This corroner report from 1576 shows the use of blows in football, and how they differed from today’s punches.

Coroner’s inquisition – post mortem taken at Southemyms, Co., Midd., in view of the body of Roger Ludford, yeoman, there lying dead, with the verdict of the jurors that Nicholas Martyn and Richard Turvey both late of Southemyms, yeomen, were on the third instant between three and four p.m. playing with other persons at footeball in the field called Evanses Feld at Southemyms, when the said Roger Ludford and acertain Simon Maltus, of the said parish, yeoman, came to the ground, and that Roger Ludford cried out. cast him over the hedge, indicating that he meant’ Nicholas Martyn. who replied ‘come thou and do yt’. That thereupon Roger Ludford ran towards the ball with the intention to kick it. whereupon Nicholas Martyn with the forepart of his right arm and Richard Turvey with the forepart of his left arm struck Roger Ludford a blow on the fore-part of the body under the breast, giving him a mortal blow and concussion of which he died within a quarter of an hour and that Nicholas and Richard in this manner feloniously slewe the said Roger.

Jeafferson, J.C. (ed.), Middlesex County Records, London 1887, p. 97.

Blows with the forearms is a strange description, but seem to imply some sort of a hammer blow, and not straights. At this point, nothing seems to differentiate Britain from other nations, at least in the realm of punching. As we have seen, such blows were commonly found in Europe, and many games could include them.

The first account of an organized boxing match in England is said to have taken place in 1681, between two servants of the Duke Albermarle.

Yesterday a Match of Boxing was performed, before his Grace the Duke of Albemarl, between the Dukes Foot-man and a Butcher, the latter won the Prize, as he hath done many before, being accounted (though but a little Man) the best at that Exercise in England.

True Protestant Mercury of December 31, 1681, p.2.

The way the text describes boxing hints at the fact that this was already a fairly common term, and we can deduce that it had already existed in some form before that event. Contrary to popular belief, the match did not involve the famous James Figg who, as far as we know, never fought in an actual boxing tournament, but established a school and venues to present fights with fists, as well as many other weapons.

This practice rapidly disseminated all over Europe. For example, the French savateur Charles Lecour allegedly included straight punches into his own curriculum after training in boxing, since French boxing, to this point, had mostly contained open palm strikes and kicks to the lower body. Lecour is also credited with introducing high kicks to the head and torso. As we will see, straight punches came to be developed through a similar process.

That subject alone would be worth a separate article, but high kicks are another great example of how certain skills require a degree of specialization and institutionalized safety in order to develop. Techniques like high kicks and straight punches to the head present a developmental phase that is dangerous to the fighter. It takes dedicated efforts for beginners to be able to kick at an opponent’s head without falling or getting their leg immobilized by their adversary. Punches to hard targets are quite painful at first, accompanied by high probabilities of fractures if done incorrectly. In societies where weapons are commonly carried, the risks of a broken hand would probably outweigh the slim chance of a punch knocking out an opponent.

With the advent of the Marquis of Queensberry rules and the widespread use of gloves and hand wraps, we see the appearance of punches given with an horizontal fist instead of a vertical one, as well as hooks and haymakers now rendered useful through new equipment and rules that favoured infighters. Prior to this era, boxing rulesets allowed grappling above the belt, which limited close range punching. Though more importantly, the absence of gloves and hand wraps meant that punches needed to be fundamentally different in order to avoid serious injuries.

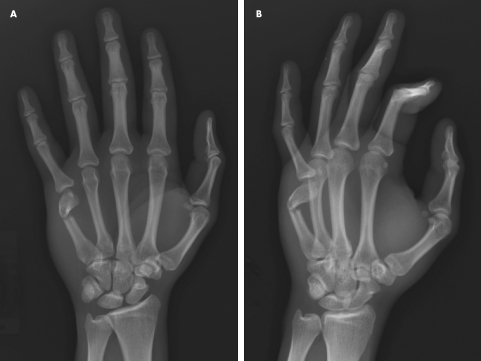

The problem with punches

Looking at boxing, one would easily think that punches are not only easy but perfectly safe; at least for the attacker. Yet, people with knowledge of bare-knuckle fighting will know that the bones of the hand are infamously fragile, especially the metacarpals. When trying to punch a solid and irregular target, it is surprisingly easy to break those bones, most often the one connected to the little finger. This fracture is actually so commonly associated with the action of punching that the medical term “boxer’s fracture” is the modern clinical diagnosis.

One only needs to take a look at the recent advent of the Bare Knuckle Fighting Championship, or BKFC, an event which promotes a return to bare knuckle prize fights. At the first event of 2018, three out of ten fighters suffered broken hands. Despite some of the publicity surrounding it, the rules are not those of the London Prize Ring, and are in fact much closer to Queensberry’s, only without gloves and with very minimalist hand wraps. Because, while the knuckles are indeed bare, the wrist itself is still quite supported, which was unknown under LPR, and which plays a vital role in the way modern boxing is fought today.

Comments left by professional boxers who took up the bare knuckle challenge, such as Paulie Malignaggi, are quite enlightening and are actually of great help to understand the subject of this article. Malignaggi, a former welterweight WBA champion, broke his right hand in his first – and last – bare knuckle fight in 2020, and this is what he had to say about punching without gloves:

The one tricky thing about bare knuckle fighting is that in boxing, you’re used to punching through your opponent, not at them. That’s the big one, and why MMA guys would have more of an advantage because the padding on their gloves are less. MMA guys are not used to punching through guys.

Bare knuckle boxing is too bad for the hands. I took damage in my hands in that fight that I still feel today. I can’t fight in that kind of combat. Stylistically, it’s not that difficult, but it’s hard on my hands. I would consider more bare knuckle fights but it’s a shame my hands are damaged. The damage my hands took in fighting Lobov for 10 minutes I still haven’t recovered. My hands are OK as far as everyday life, but I wouldn’t be able to punch right now.

Paulie Malignaggi – Boxing Scene interview

Ishe Smith, former IBF junior middleweight champion, told of a similar experience in his first Valor Bare Knuckle fight:

Definitely different and something to get used to. I hurt my hand in there a little bit. You feel every punch you hit [an opponent] with. In boxing, you don’t feel anything, hardly, unless you throw the wrong punch. Here, every punch you hurt him with, it hurts me too. You have to be a savage to do this.

Ishe Smith – Boxing Scene interview

The idea that boxing gloves, and hand wraps, allow for more powerful punches than would be safely possible without was already documented in the early decades of the Queensberry ruleset.

This article from the French magazine Très Sport, published on january 1st 1924, describes how boxing gloves were being officially increased in size, from four to five for lightweights, and six ounces for medium and heavy weights, in order to better protect boxers’ hands; which apparently had seen a sharp increase in fractures since the introduction of this equipment nearly 40 years earlier. It is worth noting that six ounces is still significantly lighter than the modern standard of eight to ten ounces of the WBA. Furthermore, the very minimal hand wrap that is shown at the left is the only one that this new ruling allowed, while the one on the right, very loosely resembling the modern version, was now illegal. The article mentions how some boxers cheat by “armouring their fists” through the use of these wraps, allowing them to hit with increased power.

Hands under wraps

Heavier types of bandages had been used before, namely in the controversial match between Jack Dempsey and Jess Willard in 1919. Rumours floated that Dempsey had somehow increased the weight or thickness of his bandages, possibly through the use of plaster, which resulted in Willard’s broken jaw. Though the use of plaster in hand wraps is known and still attempted today (see the 2009 Antonio Margarito case) the story was never proven, but it seems that it did much to make the issue of hand wraps a contentious one in the boxing world; as the 1924 article seems to allude when it mentions American boxers. Similar stories existed about other champions such as Bob Fitzsimmons, who was an early adopter of hand wrapping, while boxers like Georges Carpentier used none.

Gathering sources on this subject confirmed a prior impression: that the history of boxing is a surprisingly under researched subject. For such a popular sport, it is remarkable to see that the subject of rules and equipment is still mostly unexplored, with most of what is being written consisting of unsourced notions, and often faulty ones.

It was then difficult to find out when certain developments in equipment and rules appeared, such as hand wrapping. The mainstream literature usually draws a simple line between London Prize Ring and Queensberry rulesets; between bare knuckles and gloves. There is an understanding that the size of gloves progressed, if only by looking at the photographs of former champions, but anything prior to the 1950s or even 70s is unknown or misunderstood at best. I then had to do the research into actual primary sources to understand how the practice of hand wrapping came about.

While hand wrapping was somewhat present in the Greek and Roman worlds, it faded out of European practice along with the disappearance of pygmachy and pankration, and was only a subject for history books until the late 1880s, with the Queensberry ruleset famously introducing padded gloves to championship fights. We first find mentions of “skin tight gloves” being worn as makeshift bandages in 1887. These are described as tight leather gloves with fingers cut off, and worn to give protection to the knuckles and wrist. It is unclear if they were worn strictly on their own as boxing gloves, or also under them as handwraps.

It is important to note here that, in its first decades, the Queensberry ruleset was not as strict as it is now, and left a lot of details to interpretation. Like previous rulesets, it relied heavily on fighters to agree about certain points and requirements before a fight, sometimes even right as they stepped in the ring. The case of one of the first use of hand bandages is a great example of this situation.

In 1897, a fight took place in Buffalo, between two American boxers, Jack Dougherty and Johnny Laughlin. The contest was nearly cancelled when it was revealed that one of the fighters had wrapped his hands with oakum, a type of tarred rope used to seal ships and water pipes. The boxer in question, a Philadelphia man named Jack Dougherty, argued he was wearing those contraptions to protect his previously broken hands. At first Laughlin refused to fight him, but eventually relented. This proved to be an adverse decision, as Dougherty went on winning the fight by a knock out after only three rounds; ending Laughlin’s two years’ victory streak.

From the 1900s up to the second world war, the issue of bandaging the hands kept coming up to the fore, with boxing associations going back and forth between allowing and banning them; and often giving fairly vague instructions around their use. Those who were against them argued they were dangerous, and used primarily to increase the power and violence of punches, using electrical tape instead of medical tape around the knuckles to increase the stiffness, while their proponents argued they were there to protect the fighters’ hands. The construction of boxing gloves certainly did nothing to help, with the loose padding often being pushed aside around the knuckles.

Today, the use of hand wraps is tightly regulated, with officials surveying the whole process. They are still seen as an avenue to increase a boxer’s punching power by illegal means such as adding plaster, but mainly they serve the purpose of preventing injury, and, as we saw before, they do such a great job at this that removing them forces boxers to change their punching technique.

Conclusion

All of this brings us back to our original question: why are straight punches seemingly absent from most of humanity’s martial past? As I observed earlier, the act of punching with the knuckles to the head is a very risky maneuver, especially for someone with little experience in doing so. Most fractures of the hand can be repaired today, though usually not without leaving stigmas, but in the world of pre-20th century medicine a hand fracture could easily cripple someone, and make them unable to earn a living. Even relatively simple injuries today can result in debilitating symptoms if not treated early. Once fractured, a boxer’s hands become increasingly prone to further breaks. Though once punches are mastered, they become a very useful weapon in boxing matches, and this is where I would like to make a point.

One observation we can make when examining the appearance of punching in martial art history, is that it mostly seems to appear when a favorable context is itself present; one where two or more opponents get to exchange blows in a semi or highly controlled scenario. Once the threat and immediate consequences of a broken hand are diminished , and the benefits of throwing straight punches becomes too significant to ignore, the fighters might realize, perhaps at first by accident, the value of these blows and start to devise ways to make them a safer and more effective technique. As mentioned before when discussing savate, the same could be said of high kicks, which are fairly risky techniques, although for different reasons, such as losing balance, or being grappled. This might also explain their complete absence before the introduction of safer training spaces and organized rulesets in the early to mid 19th century.

In recent years, it has also been theorized that many other martial arts started to include high kicks through their exposure to savate. The most well documented case being karate, where high kicks only started to appear in the 20th century. The Bubishi, and most of the corpus of ancient Japanese and Chinese martial arts texts make no mention of high kicks, and for that matter straight punches to the head also seem to be absent. In their place, we find hammer fist to the nose, palm strikes to the chin and gouging the eyes.

Similarly, straight punches might have only a limited value compared to the risk of injury they present. Wrestling would be a more polyvalent style of fighting that lends itself to managing attacks with weapons such as knives and swords, but we should not exaggerate the use of these tools either. Just like today, not every fight was a life or death scenario where opponents pulled out their knives and killed at the slightest provocation. Such an act could bring about serious consequences for the perpetrator and just as today, many fighters simply did not wish to kill their opponent; or even injure them at all. Punches would still serve a purpose- unless legally restricted- and hammer fists and palm strikes would present a safer way to bring about similar results. One that may also have felt much more familiar to people used to fight with swords and sticks, as we have seen earlier with the Dalmatian mercenaries fighting the Venetians.

Another common observation is how gloves -and perhaps more importantly hand wraps- brought about the introduction of the horizontal punch. Prior to Queensberry, punches to the head were given with an horizontal fist. Such a technique does limit the speed and power of a punch, but as we’ve seen with the case of modern bare knuckle fighters this may not be such a bad thing as one wants to avoid punching through the target. The vertical punch tends to solicit the bicep, which partly acts as a brake, while a horizontal punch relies more on the shoulder muscles, which is especially useful with inside rotations in hooks and haymakers, both very useful from a closer range. This closer range is made a lot more important once the Queensberry rules remove grappling from allowed techniques, and that fighters can exchange multiple blows from in close.

Vertical punches remain well into the 1920s, though almost exclusively with jabs. Although it slowly gets replaced by horizontal punches, the practice can still be seen today; particularly when a boxer seeks to land a jab from a long distance.

Hammer strikes and backhand blows also disappeared around the same time. The first Queensberry rules did not ban them- as evidenced by the victory of Quebecer Georges Lablanche in 1889, using a spinning backfist to knock out “Sanspareil” Dempsey -but they were often refused by opponents; at a time where rules were still partly agreed to before a fight. At some point the WBA decided to specify that blows could only be dealt with the front of the knuckles, eliminating these strikes from the repertoire. Interestingly, they are still seen today in MMA, often in spinning attacks, but especially against downed opponents, in a way that couldn’t be closer to Antique and medieval illustrations.

As explained in the introduction, I chose to focus this article mainly on European practices, but the situation did not necessarily appear to be much different when looking at available sources describing East Asian martial arts, with straight punches to the head being fairly absent; unless again some form of organized contest facilitated their development. The same theory could explain the appearance of kicks to the head, which were developed in savate salles of the 19th century. Prior instances of kicks seldom go any higher than the lower abdomen, either in Europe or the rest of the world. Regardless, without trying to introduce a universal theory on the development of straight punches, I do think that this does explain fairly well how they came about in the European and North American context.

Hello Maxime,

I”m Torsten Schneyer, Hema instructor from Germany and I really enjoyed this one, great work!

I want to add a source that blows your time frame a little bit: there is an early renaissance codex with mainly medieval fighting teachings that describes punches, most likely straight ones.

The work is Ms Dresd.C.487 and you can find in wiktenauer.com.

The punches withe the fist can be read in a chapter about wrestling and are called “Mordstoss” which translates to “killing strike” or “killing thrust”. The wording and some if the targets, for example the heart while standing, indicate a straight punch. Other examples like the one to the temple are debatable and could be executed with a hammer fist, though.

Fortunately this source does not undermine your main point. Because first of all it’s quite rare, may be the only medieval manual about fist fighting and contains only a small number of blows with the fist. Secondly most ift them go against soft targets like belly or neck, with the temple as an exception.

with best regards, Torsten

Hi Torsten,

Thank you for the comments. So my point was really about strikes to the head using the front of the knuckles, as punches to many other parts do not carry the same risks of injury. I could not find the techniques you mention on the Wiktenauer entry for the manuscript, but I would be curious to see them. Petter actually includes many punches to the chest, including with both fists at once. The first two parts are actually focused on defenses against these punches, and he has this to say about them:

“As it is usual, and mainly amongst the Dutch, where there is any sort of quarrel or discord between people that has risen so high that a physical fight follows, that they punch each other on the chest and use the heavier fist punches later on during the fight, we have decided to start of with the chest punches, those being the actual beginning to start the fight: later we shall discuss all grips in order.”

It’s not entirely clear how these punches are made, but they could very well be straight punches, though again to the chest, which isn’t quite as dangerous. The way that the fists are closed in his illustrations also make me doubt that these were meant to land with the knuckles, at least not with great power. The thumb is mostly lying on the side of the index, with the phalanges pointing somewhat forward. A fairly dangerous position if one was to hit the cranium, but good for a backhand or a painful jab to the stomach.

All the best, Maxime

Fantastic article — thanks much for this mighty fine bit of research which, by the way, dovetails with my findings and others in the Rough ‘n’ Tumble community.

One question. You write, “The horizontal punch tends to solicit the bicep, which partly acts as a brake, while a horizontal punch relies more on the shoulder muscles, which is especially useful with inside rotations in hooks and haymakers, both very useful from a closer range.” Can you clarify? I’m assuming one of those horizontals was intended to be a vertical?

Thanks again and Kindest Regards!

Thanks for the comment! I corrected that paragraph. Indeed, the first type mentioned should be “vertical” instead of “horizontal”.