By Maxime Chouinard

Although the art of fencing was quite developed in France, the military did not establish any unified method for soldiers or sailors until the mid 19th century. Until then, fencing instruction continued as it had for centuries: regiments and ships could have several fencing masters and provosts in their ranks – Bouët’s ship had no less than six – who would provide instruction to soldiers and officers; often for a fee. A captain could choose to pay a fencing master to instruct his whole crew, but they were under no obligation to do so or to follow a set method.

The following instruction was published in 1847 by Edward Bouët-Willaumez, who was then captain of the Caraïbe steamship. Bouët was born in 1808 in Brest in a merchant family. He inherited the title of count from his uncle the Admiral Jean-Baptise Phillibert Willaumez who served in the Navy during the First Empire and had no children of his own.

After leaving the naval school of Angoulème in 1824, the young officer’s career was filled with positive as well as contentious achievements. He became involved in the Greek War of Independence and the colonization of North Africa. He was promoted to first lieutenant and put in charge of the repression of the slave trade along the African Coast and served as governor of Senegal from 1842 to 1845.

In 1845, he took command of the steamship Le Caraïbe until 1848. This is during this experience that he will write the following note. Bouët continued to climb the ranks through the succession of governments in Paris up to the rank of Rear-Admiral. He participated in the Crimean War, the Second Italian War of Independence and the Franco-Prussian War. He died in 1871 following a liver disease he contracted in Senegal.

I also included in this translation a second text. This one is the fencing regulation for ships of the fleet which contained the first official fencing regulation for French sailors and marines. This was most probably part of the overall effort of regulation which led to the creation of the Joinville-Le-Pont school of gymnastics and fencing. While Bouët’s name is never mentioned, it seems quite evident when comparing the two that his note was the influence behind this regulation, with few changes made such as the addition of the bandoleer cut and the removal of the point down guard.

French sailors practicing the 1877 manual salute aboard Le Formidable in 1897

While these two methods are very short, they are fairly complex when compared to contemporary cutlass drills. It is typically French, in that it favours the point, a guard of tierce, a bent arm and draw cuts, although not as present as in later methods. As both notes mention, this method represents the style of contre-pointe. The 1851 regulation was most likely kept in service until the introduction of the 1875 gymnastics and fencing manual.

Maritime and colonial annals – 1847

No. 76: Report to his excellency Vice-Admiral Baron de Mackau, peer of France, minister of the navy and colonies, on the results obtained following the transformation of a transatlantic liner of 450 horsepower into a frigate, and on the numerous innovations introduced in the crew and the material of the Western African Coast, by the Count E. Bouët-Willaumez, flag captain.

Supposing that the material boarding could be followed by a personal boarding, like, for example, in the case of an encounter between two steamers, I believed necessary to train the 80 men of the boarding company of the Caraibe not only to the exercise of the sword, as the 1827 ordinance limits itself to, but also to the handling of that weapon; you truly have to have never stood in front of the threatening steel of the enemy to deny that the habit of weapons gives confidence and boldness which are foreign to a man who does not know how to take more advantage of his sabre than he would a broom handle. No doubt that some will cite cases where audacity and energy negated this ignorance of the rules of fencing, but these cases I believe are exceptional, and I do not understand that we let our sailors be strangers to the handling of the sabre when we familiarize our soldiers with bayonet fencing.

Strongly imbued with these ideas, that English officers do not disdain like we do, I succeeded in convincing the commanding staff of the Caraibe, who, first skeptical – as they were we should say new in their application – were later on convinced of their practical rightness. I gave the officers who were part of the boarding a note on the handling of the sabre, a note I conceived and redacted myself after numerous assaults with good masters. These officers had to gather all the masters and provosts on board; they were six, who were reduced to four later on due to the impossibility for the other two to get out of the routine of their method and to shape it to the simplicity of the strikes detailed in my note.

Squads of 15 to 20 men were put under the orders of the fencing masters, who had to proceed according to my principles, principles that I maybe think of some usefulness to present here, as all our ordinances, all our regulations, are silent on this subject. These principles suppose that you possess, and that is the case of nearly all our officers, the basic notions of the handling of the foil.

Handling of the sabre

Of the guard

The handling of the sabre consists of attacks and parries.

The attacks are done in point or thrust, of contre-pointe or cuts.

Thrusts do not necessitate that you uncover yourself like cuts, and making more severe wounds than the latter must generally be preferred.

The guard and the lunge are the same, in regards to the position of the body, than the guard and lunge in the handling of the foil. It is not the same for the position of the arm and the sabre; there are two very distinct ones:

Guard, point over!

Guard, point under!

In the guard of the point over, the hilt of the sabre is in the right hand at the height of the nipple, nails under, the blade half unwound, the edge outside, the point at the height of the eye for thrusting. It is the guard employed by default and the one which is the most appropriate for attacks.

In the point under guard, the nails are turned outside, the elbow is horizontal, the wrist at the height of the chin, the edge over, and the point, lower than the hand, threatens the middle of the opponent’s body.

This second guard, rarely used, is nonetheless good for defense of the under if we adopt as a parry a half-circle nearly continuous. It is also very favorable to a thrusting riposte.

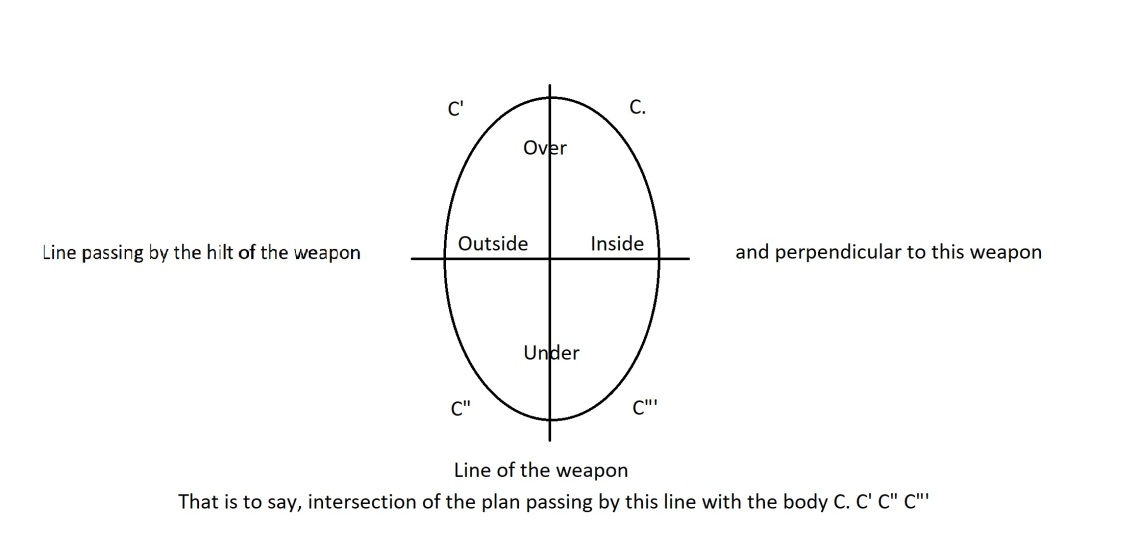

To render more sensibly the details of the attacks and parries, I will trace an oval representing the body of the man that I suppose to be cut by two perpendicular lines separating the over and under, and the inside and outside.

The thrusts are generally simple and consist of disengagements, either inside, either outside, and in straight strikes, being any strike that removes the blade only slightly from the line. This is the method that you must employ against an adversary familiarized with the weapons because then you uncover yourself little or even not at all.

The cuts are composed, on the contrary, of multiple and rapid feints to confuse the eye and then the opponent’s weapon. It is the method that you must employ preferably against opponents that are not very skilled with the handling of the sabre, because these acrobatics of the steel intimidate them and open their flank or their head to a final blow without thinking of using the opening that we are giving them by executing these feints. These cuts are, being engaged in the guard point over, the face cut inside, which is done with a coupé outside to inside, and from this position the face cut outside, which is done with a coupé inside to outside. Of this last position, the flank cut, which is made by a hewing cut of seconde, with a retreat of the sabre to better cut the flesh. Then, from this position, the belly cut which is made by a half-circle hewing cut, retreating for the same reason, and finally the head cut, which is made by a hewing cut on the head, by preceding it, or not, by a backward-moulinet of the sabre to double its force of action. As to the manchette cuts, inside or outside, they are just face cuts but shorter. The leg cut is hazardous. The manchette cuts, on the contrary, are very good to adopt, because by executing them we are straying little from the line: they are the ones employed by good contre-pointe fencers.

The parries

The parries of thrusts are the tierce and the quarte if the blade reaches, either inside or outside, but over the weapons, that is to say towards the upper body. It is, on the contrary, the seconde or half-cirlce if the blade reaches under the weapons, that is to say in the lower body.

The parries of cuts are blade oppositions analogous to the cuts themselves. So the face cut inside is parried with a high quarte, inside parry over the weapons. The face cut outside, with a high tierce, outside parry and over the weapons. To the flank cut we must oppose a cut in seconde, parry outside and under the weapons. To the belly cut, a half-circle, parry inside and under the weapons.

The leg cut is parried with the leg itself, that is to say that we must get into the habit of retiring it swiftly to the back at the slightest threat from the opponent and to hit him at the same moment as he had to uncover himself greatly to execute such a cut.

The manchette cuts are parried with a simple unwinding of the wrist in tierce or quarte, accompanied by a covering of the arm. The head cut is parried with prime, hand high, and riposte of thrust in seconde, if possible.

When, lacking instructors, you will be obligated to have the sabre handled by a large group to make it familiar, you should place men in the position of half left, two steps from each other, and, after having them fall into guard, you will have them first execute the attacks, then the parries, as follows, but on one rank:

Attacks

Squad, half left.

Guard, point over!

Thrust!

Guard, point under!

Thrust!

Guard, point over.

Face cut inside!

Face cut outside!

Flank cut!

Belly cut!

Head cut!

Guard, point over!

Manchette cut inside!

Manchette cut outside!

Leg cut!

Parries

Parry the thrust over!

Parry the thrust under!

Parry the face cut inside!

Parry the face cut outside!

Parry the flank cut!

Parry the belly cut!

Parry the head cut!

Parry the machete cut inside!

Parry the manchette cut outside!

Parry the belly cut!

When the men are familiarized with these diverse strikes and parries, we oppose them to each other, and the assaults begin. This is when we have them follow the parry by a riposte, which is itself one of the attacks indicated previously, either simple, either complicated with feints.

Regulation on the interior service aboard the ships of the Fleet – 1851

Fencing

9.– Men are placed in one rank. They take their distances by lifting the right arm to its full length, the tip of the fingers touching the left shoulder of the man on their right.

10.– The men are thus separated, and placed in the position of the unarmed soldier, executing first moulinets to the right, left, forward, backward and on the head.

11.– To the command: On Guard! Have them take the position of the sword guard, the left hand on the hip, the right arm bent, the right hand in line with the right nipple, the nails underneath, the edge of the sabre to the right, the point of the weapon at eye level.

12.– In the position of on guard, the men are trained to the following movements:

1st and 2nd. Face cuts to the right and left.

3rd………….. Flank cut.

4th………….. Belly cut.

5th………….. Head cut.

6th………….. Bandoleer cut.

7th………….. Manchette cut.

13.– The attacks are given in accordance to the fencing of contre-pointe, the men taking all the lunge they can, the left leg straightened, the left foot flat, the right knee over the shoelaces, the body straight and well positioned on the hips. The men come back up and take the on guard position at the command of: On guard!

S 2. Parries and ripostes

14. –

1. The parries are always taken, the men on guard, the body well placed.

2. The ripostes are given all the way, and mostly with the point.

15. – These parries and ripostes are:

1o For the face cut to the left

The tierce.

Take the opposition of tierce, the nails underneath; point the hand in tierce, the wrist high, the point low.

16.- 2o For the face cuts to the right

The quarte.

Take the opposition of quarte, the nails on top. Point the hand in quarte, the wrist high, the point low.

17.- 3o For the flank cut

Prime to the right.

Take the position of right prime, the wrist high, the edge of the sabre outside. Point in prime.

18.- 4o For the belly cuts

Prime to the left.

Take the opposition of prime to the left, the wrist high, the edge of the sabre inside.

19.- 5o For the head cut

Head cut in prime.

Take the head parry of the contre-pointe. Point in prime.

20.- 6o For the bandoleer cut

Prime to the left.

21.- 7o For manchette cuts

Retreat of the body, opposition of hand in quarte or in tierce, depending if the manchette cut is given inside or outside. Point in quarte or in tierce.

22.– When the men are well trained to give the attacks all the way, to take the parries and ripostes, they are placed in two ranks, facing each other, spaced as it was said earlier, and they march towards each other until they cross sword

23. –

1. In this position, the two ranks are trained to attack, parry and riposte.

2. The instructor commands:

1st rank. – Face cut, to the right!

2nd rank. – On guard, parry and point!

3. At the command of Give! The first rank attacks by a face cut to the right. The second parries, throws and thrusts in tierce.

4. At the command of On guard! The two ranks take back their position on guard.

It is the same for all the attacks, the parries and the ripostes.

24.– When the men are well familiarized with these movements, they can be trained with the same attacks and the same parries to the ripostes of cuts.