In the last decade, the Historical European Martial Arts movement went through a major change with the appearance of tournaments. At first very averse to the idea of competition in the fear of “sportivization”, a large part of the community is now much engaged in the practice which includes a variety of different arts such as longsword, sword and buckler, rapier (with all its accessories), dusack, sabre, wrestling, dagger and more. This phenomenon rose rather quickly when it was realized that fencers of the Renaissance used to partake in tournaments, giving a certain validation to the concept.

A sizeable part of the community also views this development with suspicion. There is a certain fear that HEMA is following the same track as nearly every other combat sport that preceded it, a path which would not be true to the ideals of the current practitioners or those of the past.

The aim of this article is not to take sides in this debate, but rather to give a certain frame to analyze the question both in its present and past incarnations. Are HEMA tournaments a type of sport?

-What is a sport?

Keep in mind that there are many different views on the subject, and although they are mostly the same, not everyone agrees.

So what is a sport? Let’s first look at the origin of the concept itself. Researchers like Norbert Elias have pinpointed the origin of sports as we know it today to 17th century England. Although games had been played for centuries, there are some very important differences about sports, so much that people came up with a completely new word to describe them.

-Civilizing violence

Elias was a German sociologist who went to England during the Second World War and came up with the concept of the “civilizing process”, still quite useful today to understand the evolution of sports. According to his finds, sports came about as society itself was changing.

Games had always been relatively brutal, at least to our modern standards. We often laugh at the idea that football could have been banned in Medieval Europe, but we have to consider how far it was from today’s sport. Football until the 19th century was a very violent game with a variety of different rules depending on the mood of the players or the region they came from. Few people realize that rugby and football were once the same activity. Punches and kicks were frequent and mostly legal and could lead to death. As was often the case in pre-modern games, breaking the rules was not necessarily seen as a fault but rather an opportunity for the other team to retaliate. Deaths during play were often ignored as it was the result of an intentional play.

Bruised muscles and broken bones

Discordant strife and futile blows

Lamed in old age, then cripled withal

These are the beauties of football

—The Beauties of Foot-ball, 16th century, Anonymous, translated from old Scots

Calcio Fiorentino is an old form of football which was played in Florence from the 16th century up to the 17th century. It was revived in the 1930’s and is still played today with much stricter rules.

But as the modern age came about, the tolerance towards violence became lower. Following the English Civil War, society was being democratized. The parliamentary system which was no more submitted to the monarchy privileged discussion under strict rules to make sure that argumentation would be the key to power, not simply the force of arms. It was a society which asked for more and more self-restraint of its citizens as the self-control values of the nobility slowly shifted to other classes. It’s under this phenomenon that sports such as boxing and fencing came to be developed.

We often tend to see sports as an ancient tradition inherited from the Greeks. We look at similarities and ignore the large differences in order for it to confirm our views.

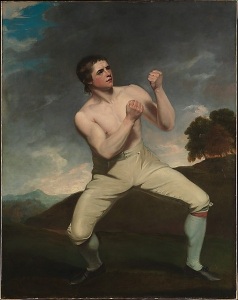

Boxing is often linked to the antique combat games of Greece by highlighting their commonalities and ignoring their differences, but both were vastly different.

Pankration, for example, was not a sport; to Elias it was an “agon”: an extension of war in a society where war and violence were an integral part of life. This explained the lack of rules and the fact that deaths were relatively common and considered “normal” and even “glorious”. Rules were flexible and unwritten. They were the object of tradition, not bureaucracy, and reflected the reality of a warrior class for which competitive games were means to train for war, and war a mean to train for games, as Philostratus cleverly wrote. This view was still present in a certain sense in the Renaissance where deaths during fencing tournaments were often more or less tolerated as they were considered part of the process of producing men capable of defending the State.

The notary book of Jean Papon from 1580 notes how deaths in fencing bouts were acceptable as they were part of the process of training men to fight for the Republic.

But as the State claimed the hegemony of violence through the establishment of police forces and national armies, it too grew intolerant towards violent sports and searched to repress them. Stick fighting which used to be a universal hobby of the working class of Europe soon became unique to only certain regions, such as Ireland, where faction fighting was severely repressed in the mid 19th century. Reformed sports such as Hurling and boxing were proposed instead to lure people away from those unruly activities.

But violence could not be completely wiped out of certain sports as it was a source of excitement and emotional control. This is why today many sports allow certain things which would mean legal trouble if it was done outside of a game; for example fighting during hockey games.

-The invention of “Fairplay”

But then what was there before sports came about? There were games. Games are inherently different and are a subcategory of “play”. Play is spontaneous in nature, for example, children playing with toys rarely follow a structure with many established rules. A game on the other side is organized, but as we will see not to the level of a sport. Now all of them have a defining principle in common: they are all non-utilitarian; they do not directly serve an essential purpose such as work. This is where combat sport can be an ambiguous category, it can be considered a martial art if its main purpose is to prepare for fighting or self-defense, but often time this is a secondary goal – if it even is one- and so people will rather refer to them as combat sports or games.

Glima was one of the last type of European wrestling to have been transformed into a reformed sport. Even in the early 20th century, Icelandic champions demonstrated a variety of holds which were now illegal in most styles. The older version has survived through the practice of Combat Glima.

From the 17th up until the 19th century, most cultures outside of England had no word to describe the concept of a sport and most had to borrow it. German writers such as Pückler-Muskau commented in 1810 how there were no equivalent to the word “sport” in German and that it was as hard to translate as the word “gentleman”[1]. As sports became more popular in Germany the term was finally included in the early 20th century. Even the French had no word for it, even though the word originated from the French desport which simply referred to pleasure and entertainment, quite far from the complex concept of modern sport. The word “fairplay” itself is now part of the French language as there was no such concept in pre-modern games. Sports differ from games because they are regulated through strict and universal rules enforced by a centralized bureaucracy and promote pleasure to the spectator as well as equality of chances. Sports were also pursued as a personal improvement for both mind and body, an idea that was gaining ground in the 19th century.

The 19th century revival of the Olympic Games was in a way very close to HEMA. Many of the sports presented had not been practiced for centuries and had to be redeveloped, but the format and context of the Games was totally different.

But then what is a sport? Allen Guttman proposes a definition; for him, it is a non-utilitarian contest which includes an important measure of physical as well as intellectual skill. It must also meet seven criteria to be considered a sport in the modern sense of the word. Although Guttman’s theory is not the only one, it is arguably the most popular.

Note that these criteria are not an authority by themselves on what is and isn’t a sport. There is no “Guttman Society” which will deliver sports accreditation if HEMA fits in those categories and you will still be free to call HEMA whatever you like after finishing to read this article. Guttman simply observed the characteristics of what constitutes a sport in the modern setting compared to the pre-modern games (pre 17th century).

-The seven characteristics of sports according to Guttman

Secularism: Sports are not played for a religious purpose. The ancient Olympic Games and the Aztec Ōllamaliztli ball game would not fit since both had heavy religious connotations. Aside from humorous references, tournaments in the HEMA scene are completely secular in nature.

Equality: Sports seek to limit the disparity between players so that ideally only skill can determine the winner. In theory, everyone who has the skills to compete can join a sport, which wasn’t always the case in pre-modern times when class or ethnicity could be used for exclusion. Of course, it is impossible to eliminate all inequality as one opponent will always be faster or stronger, but weight classes, for example, exist for this reason. For the moment, very few HEMA tournaments have instituted such classes, although some now discriminate in terms of experience or weight for wrestlers.

Specialization: After a certain time the rules of sports become so interiorized and ingrained that players begin to specialize their roles and have a team of experts helping them. In hockey, you will have captains, defenders or allies. Boxers will specialize in certain styles of fighting. Olympic swimmers will have a retinue of coaches, psychologists, and other professionals to help them win. Slowly you see HEMA fighters having a coach or two around them, and professionals are now starting to offer their services to enhance the performance of athletes.

Rationalization: Sports rules follow a logic of instrumentalization. Gymnasts no longer jump on a real animal but rather on an immobile “horse”, fencers use weapons which have little in common with the swords they were supposed to imitate. Rules and regulations become means to an end and no longer a representation or simulation of a real setting. HEMA is still far from this phenomenon, possibly because it partly exists due to a reaction to combat sports like Olympic fencing. That said there is more and more a standardization of equipment, not only in weapons but also protections and physical settings. Tournaments now publish a selection of equipment which is obligatory or proscribed.

Bureaucracy: Every level of sports today is bureaucratized, from children leagues to professional ones. Ancient sports were rather controlled informally, by the community or the Church. Federations have started to appear in HEMA and slowly are establishing certain standards and bureaucratic practices.

Quantification: Our modern world is obsessed with numbers and measurements. It is difficult for us to imagine that in the ancient Olympics disc throws were not measured and running times were not taken. Time limits for combats were also absent. Most HEMA tournaments today are very different and count points and time.

Records: Modern sports are all about breaking the last record. In a way, it is a reflection of our society, where we always wish to strive for progress in every area of our lives. Records are then seen as a confirmation that progress is made.

-So… is it?

Are HEMA tournaments sports? In the modern definition, I would say that no, not quite. Was it in the past? In some instances yes, in others not and referring to Guttman’s criteria will help you to determine what you are looking at.

I think an important question to be asked is rather: Should HEMA tournaments be a sport? To what extent? And even more importantly: Why? While many discussions are made around the rule sets, few are made to ascertain the overall goals. It is by knowing why you do something that you will understand how to reach your goal and avoid pitfalls. It is also relevant to consider Guttman’s observations: that given time, every sport becomes increasingly bureaucratized and commercialized. As more and more different people join HEMA tournaments, what you think defines HEMA as a sport today might not be shared by the next generations who might choose a different approach. This is a risk that you must be ready to take.

[1] Briefe eines verstorbenen. October 9th, 1810

Further reading:

Norbert Elias and Eric Dunning: Quest for Excitement. Sport and Leisure in the Civilizing Process.

Allen Guttman: From Ritual to Record.

Reblogged this on .

Thanks!

Great article, thanks for posting it, I found it very informative and interesting! It’s incredible to think that we obsess so much over these “designations” of what it “is” or “isn’t” that the value of the activity takes a back seat to the peculiarities of the rule sets, or limitations of equipment used. The feelings of competition and comraderie far outstrip the issues, granted as a community we need to improve these aspects, but how long before our sport track equipment will mirror all the things we point our collective HEMA tongue at the Sport fencing scene? It’s curiously hypocritical sometimes I think. Surely there are things we can focus on to praise all around instead of chiding each area so much!?! Thank you for your efforts, I appreciate the information!

Thanks! Glad you liked it and glad that it creates some reflection!

It’s not so much HEMA as sport, but e.g. longsword fencing or rapier fencing as sport. Maybe eventually a ruleset and standard equipment will develop in longsword that will be as divorced from its historical roots as Olympic fencing is, and take on a life of its own. That would be a pity, but would not detract from HEMA.

I firmly believe that tournaments are a good idea. Apart from being fun, they provide an opportunity to test techniques with a non-cooperative partner in a stressful setting. I see merit in keeping different rulesets, as different rulesets favour different attributes, techniques and tactics, and stop us from training for just a specific ruleset (as is the case in Olympic fencing).

Then, there are many historical weapons for which there are no (or no convincing) tournament settings, such as halberd or dagger.

While you’re at it read Konrad Lorenz’s “On Aggression.”

very nice article. The question whether HEMA-tournaments is sport is occupying me as well. Though I am working on the MA perspective. So this article was greatly complementary and interesting for me. Thank you

I worry at times when WMA is on the rise that as it becomes sportly that a precedent will be set that in essence makes a shitty game that is distant from the spirit of martial intent. As an example it is commonly seen that for rules in longsword tournaments of the HEMA style that after contact the engagement is halted and points scored. This to me is very disappointing… To see the rules structured in such a non combative way… I would much rather see it move to something more akin to mma… And I worry that as it’s popularized it’s going to go to the weak side.

Originally sport was theorised to have been ‘training for war’. If I may mention that the Spartans were banned from the ancient Greek games because their martial mindset crippled/killed their opponents and no one hence wanted to wrestle the Spartans. We might sense a dichotomy right there and see the possible root of sportification of martial arts right there. Yes, martial sports have their problems with mindset erosion but do we want fatalities every training session and the martial sport activity is possibly better than nothing, a fighter that doesn’t fight will not be able to hold onto the mentality for long. (All theory for me.)

If you read my article you will see that I also talk about the ancient Greeks. This is not usually understood as a sport, as it was developed in 17th century England, but an Agon; an extension of warfare. As for the Spartans, do you have a source about this banishment? As far as I know the only time the Spartans were banned from the games is because they violated the games sacred truce by attacking Elis in 420 BC. They refused to pay the fine and as a result were banned from the games that year. It is very unlikely that anyone would have been banned for brutality.

“For this reason the Spartans did not participate in the pankration. Seneca reports that for a Spartan to acknowledge defeat was considered too humiliating and consequently the Spartan rulers forbade their citizens to participate in either pankration or boxing.” p.81 Olympia, Drees (1967)(SBN 269 670157). So having just read some supporting information, the brutality (breaking fingers and arms) whilst accepted risks (and for some strategies) I can only wonder that the thing at risk was not only the Spartan pride, but their unwillingness to concede, tap out, submit. That must have led to some very nasty injuries beyond the broken limbs they already considered ‘normal risks’. On a psychological level, it may come down to “could you really kill someone or not?” If a HEMA tournament fighter could really kill someone and not have ethical qualms about it, then he is a warrior mentality. If he cannot, (as myself I suppose) then he’s not a warrior. He’s a sports fighter. That has to be the difference between the sport and the martial art. Mindset. And this says nothing of the sport’s excellence. It might be very excellent, and the moves certainly could kill an enemy. But that’s not what delineates it. (Again, my hopeful conjecture.) Hopefully this angle is of interest.

Thank you for the article, it was very thought provoking.

The ‘Spartan vs everyone’ issue is interesting. Spartans, like the European Knight or Japanese Samurai, were a aristocratic warrior class, trained from a young age for combat. Other combatants didn’t have the advanced physical or psychological training given. I can see how this would be counter productive to their training and morale.

The ‘qualms’ issue isn’t purely training, it’s a base psychotic nature. Ed Bundy didn’t have any qualms; soldiers with modern training have had the required actions ‘normalised’. The subsequent PTSD issues are after-effects of performing a non-normal action.

In the end, humans are insanely violent, more so than other animals who kill for food, or fight for social dominance or protection. The creation of sport is progressive action to manage the base desires of violence in man.

Refusal to submit was common among all the Greek cities. There are various stories of fighters dying because they would not submit, and these fighters would actually receive more acclaim than the victors.

Also note that my article is not meant to establish what makes better fighters between sport or martial art, or what constitutes a martial art (many authors would say that it is the exclusivity of warrior elites for example). This is a whole other debate.

If you will allow input from a very recent newcomer, I would say that HEMA is not a sport.

In a sport the equipment, playing area, scoring rules etc are standardized to ensure that it is the participant skill alone that determines the outcome of any given match. That does not appear to be the case with HEMA.

When and if it gets to the point where sabres only fight sabres and long swords, long swords then HEMA will be a sport and will have lost much of its appeal. My interests come from 1812 re-enacting and ultimately I would like to match the English light cavalry sabre and manual against its American and French equivalents as well as tulwar and musket and bayonet all on foot and possibly on horseback. While several of these combinations are decidedly unsporting, they are however interesting.

And interesting is what it’s all about.

Interesting. I think a counterpoint is in order. I think this post has a more reductive view of sport than historical use suggests. It’s also a more reductive view of sports than current government definitions, policies and working practices use, at least in Europe.

I absolutely agree that very often, “sport” and “competition sport” have become highly conflated for most members of the public, certainly in the UK.

I’ll develop the counterpoint at suitable length, and dig out suitable support, and then I’ll post it at:

http://fightingwords-blog.blogspot.co.uk/

Hi Gordon,

You are right that this article is reductive, as it is its goal. What it does is to put back into context what is a sport in the most narrow and historical sense of the word, not in a contemporary popular or legal sense. Much like most popular or legal definitions of “martial art” do not reflect the historical reality or even the complexity of such a practice, definitions of “sport” often miss it as well. As I said people are free to call what they like “sports”, but we should also acknowledge that it would have been a concept that was quite alien to many people before the 17th and even 19th century, as the adoption of the English term itself suggest (no one had a word for such a thing) I suggest reading the works of Elias and Dunning which are really the basis of any study of historical sports and games. You will see that I am far from being the only one to hold this view, see for example: http://hrcak.srce.hr/file/60493

I’ll be interested to read your article.