If one seeks links between historical European martial arts and their Japanese counterparts it is often from a confrontational angle. It seems arduous to imagine a meeting between warriors of these two cultures as something else than a clash, each other being uninterested in actually learning anything and only in proving the superiority of their respective arts. That said when one looks at the historical facts very few fights were to be had between them. What we really witness are a series of exchange on both sides by curious scholars of the martial arts wishing to learn more about their respective passion, regardless of their origins. Needless to say, it would be wise to follow their example.

First French Mission to Japan (1867-1868)

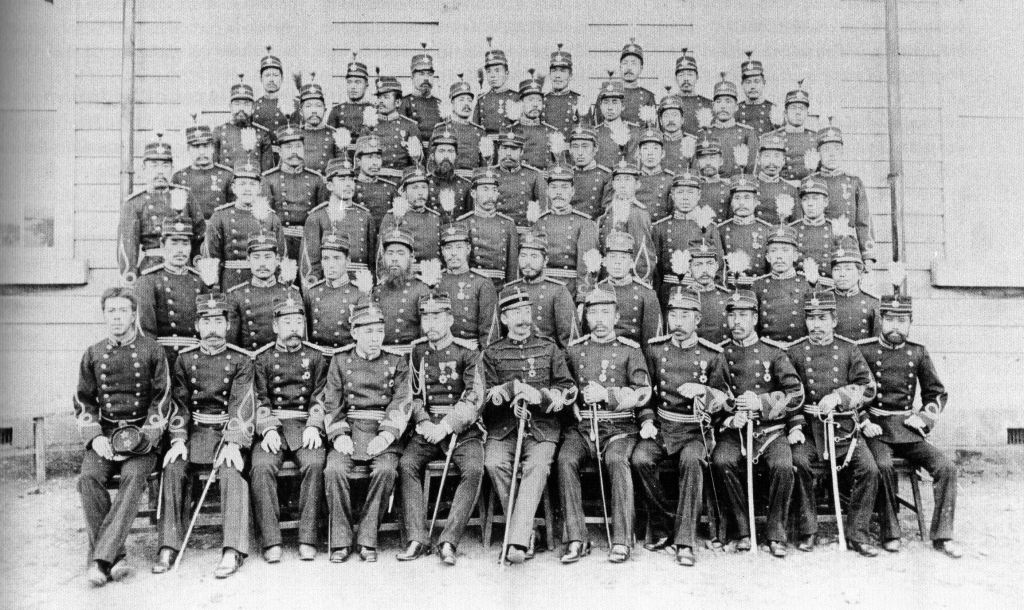

By the 1860’s Japan received great pressure from both outside and inside its own population to open up and modernize. After more than 200 years of isolationism, the Shogun finally decided to open and seek help from Western countries to modernize its infrastructure. To train its new army, the Japanese decided to turn toward different nations, among them the French who were considered one of the most advanced military power of this era. Seventeen officers and soldiers were sent by Napoleon III to meet the demands of the Shogunate, but soon the boiling political situation erupted into a civil war between the Shogunate and those seeking a return to power of the emperor. The French being caught on the wrong side of the deal were sent back but several of them under the command of Jules Brunet decided to stay and fight on the Shogunate side which was composed mostly of members of the samurai class. A naval officer named Eugène Collache also joined and was among the last 800 members to resist the onslaught of the new army and soon forced to surrender.

It is unclear if any of these officers had any time to learn Japanese swordsmanship, but Collache did showed up at his subsequent trial in traditional Japanese garb and can be seen on this portrait wearing the two swords, which could mean that he received some instruction as to their use.

Collache in “Une aventure au Japon 1868-1869”, 1874 edition.

Third French mission to Japan (1884-1889)

Even though the French ultimately fought on the losing side during their first mission and their defeat during the Franco-Prussian war, the Japanese government still invited them again to help build their new structures. The French had lost some of their reputation as a military force during the war, but the Japanese were still impressed by their commitment to fight on both these occasions even though outnumbered. They were reinvited from 1872 to 1880 and again for the third mission in 1884.

During this 5 years long mission the French helped establish the Toyama Gakko, a school for officers which eventually helped create Toyama Ryu; a now very popular style of Japanese swordsmanship. Among the officers sent to Japan for 3 years were two fencers, Joseph Kiehl a fencing master and marshal of the Logis responsible of teaching physical education and of course fencing, and also Étienne De Villaret a shooting and strategy instructor. During their stay (1884-1887), both of them not only taught but also became students, more precisely they joined the dojo of a very influential man: Sakakibara Kenkichi a master of Jikishin Kage Ryu and one of the principal promoters of what would become kendo.

By the 1870’s many fencing instructors were struggling to make a living. With the bushi class dissolved, the interdiction to carry swords, the eagerness of the new army to learn European fencing and the sudden appearance of modern guns, the Japanese instructors were suddenly left with very few students. This is where a former fencing master of Edo castle – Sakakibara Kenkichi – in 1873 held the first public exhibition of swordsmanship. A monk assisting this first event decided, along with others, to invest into a series of similar ones. Soon their popularity rose so much that the government, fearing that these fighters might join potential uprisings, banned them from Tokyo until 1876, forcing Kenkichi to take this tournament to other parts of the country.

Sakakibara Kenkichi sitting on the right corner of a kenjutsu match

After the ban, Kenkichi declined to continue directing the events and instead left the responsibility to one of his students. He continued teaching Jikishin Kage Ryu and this is where he met his European pupils.

Little is known of Joseph Kiehl other than his position and the dates of his stay in Japan. One can suspect that he was instructed at the Joinville-Le-Pont military school, a prestigious academy of gymnastics and combat created in 1852 as a mean to standardize the instruction given in French regiments of the time. Various martial disciplines were taught alongside gymnastic or swimming such as great stick, cane, foil, sabre, bayonet and boxing. Instruction continued until 1939 when the German army invaded France and dissolved the academy.

We, fortunately, know a bit more about one of his colleagues, Capt. Étienne Godefroy Timoléon de Villaret. De Villaret was a member of the French aristocracy, his ancestors being at one point famously involved in the crusades. Guillaume and his nephew Foulques de Villaret were successively Grand Masters of the Knights Hospitaller. With such a name to live up to, Étienne joined the army in 1854 where he chose to serve in the infantry and more precisely the Chasseurs à pied or Jägers. His formation as an officer took him to the shooting academy of Ruchard where he won the first position, and later the Joinville-le-Pont military school where he won the prize for “diverse fencing”.

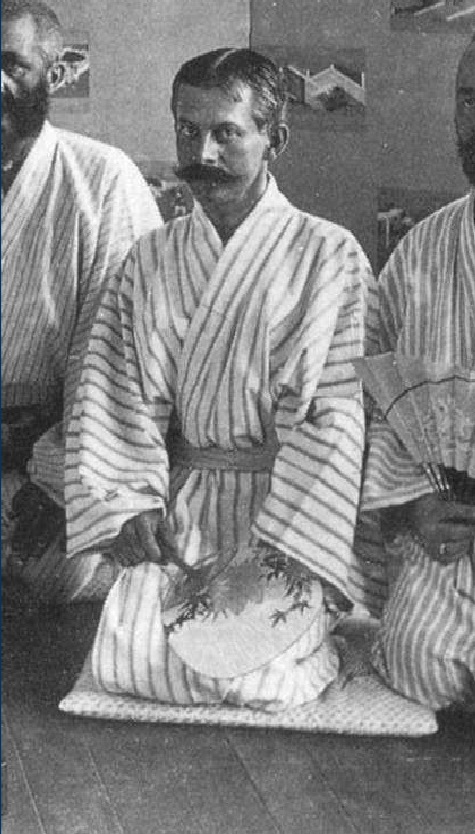

Capt. De Villaret and his Japanese students

His baptism by fire took place in Algeria during the Aurès’ insurrection in 1879. In 1884, he was invited to Japan for the second French expedition to teach shooting, strategy and to help supervise Kiehl’s classes; his efforts allowing him to be decorated with the Order of the Rising Sun. A curious man by nature, De Villaret sought to learn more about Japan and came back many times after this expedition to eventually publish a book on the country: Dai Nippon. He and Kiehl join ed the dojo of Sakakibara Kenkichi during their service. Unfortunately, no more details can be found at the moment of why or how the instruction took place, but Kenkichi seemed to be a reference at the time for travelling Europeans in Tokyo.

De Villaret went climbing the echelons and become general by the time of the Great War where he commanded in numerous battles including the Somme, Ourc, Aisne, Hartmannswillerkopf and Champagne; most of them victories. He suffered a bullet wound to the head while visiting advanced trenches in 1915 but this did not stop him from saving general Manoury who was accompanying him and fell unconscious from his wounds. This act brought him the decoration of Grand Master of the Legion of Honour and later the Order of the Bath.

De Villaret in uniform in 1915

A pioneer

But even before any of the two French officers could enter Sakakibara dojo, a German was the first to open the doors. Dr. Erwin Von Baelz arrived in Japan in 1876 to teach medicine at the University of Tokyo. When he arrived, Baelz found the young Japanese people in a state of poor physical and cultural state. Most were dismissing their cultural heritage, a fact described in his memoirs: “In the 1870s at the outset of the modern era, Japan went through a strange period in which she felt contempt for all native achievements. Their own history, their own religion, their own art, did not seem to Japanese worth talking about, and or even regarded as matters to be ashamed of.” Part of this cultural heritage were, of course, the martial arts, of which Baelz had to say: “The native methods of bodily exercise, Japanese fencing, and jujitsu, and alike were placed under the ban. The older generation would not teach and the younger generation would not learn anything but European science.” Critical of this state of affairs, the doctor found these martial arts to be perfect gymnastic exercises and a worthwhile cultural pursuit. He encouraged students to practice kenjutsu and pushed the authorities to let them practice in the university, but the memories of the civil conflicts were still fresh and the government was considering the art too rough and dangerous.

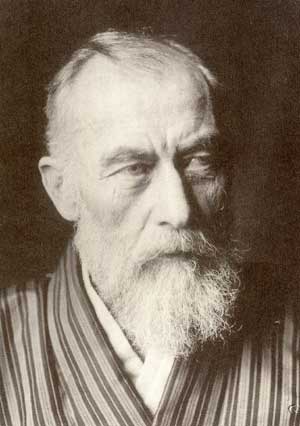

Erwin Von Baelz

A former military man and quite possibly a participant to mensur in his student days, Erwin would not let such a warrior art fade into nothingness, and following a demonstration of gekkiken in 1879 he chose to join the dojo of Sakakibara. His efforts at once again popularizing the art took hold and the sport of kendo could slowly emerge. As if it wasn’t enough, Baelz also had contacts with a certain Jigoro Kano who was then busy promoting his new wrestling method. Baelz helped the man and judo eventually became the international sport it is today. He also took up kyudo or Japanese archery. If it wasn’t for Dr. Von Baelz insistence, perhaps Japan’s martial arts would also have to be learned through surviving literature.

Other European students also joined Sakakibara’s dojo and even participated in the public gekikken tournaments, such as Thomas McCluthie, a clerk of the British embassy. Another German also joined them, Heinrich Von Seibold, a famous archaeologist and an apparently gifted fencer.

Heinrich Von Seibold

Count Koma and fencing

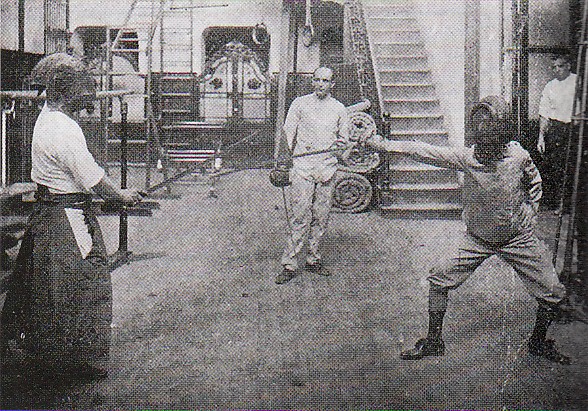

Two very interesting pictures of the grandfather of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu can be found in which Mitsuyo Maeda is fighting against western saber fencers. Maeda was a seasoned instructor at the kodokan and was sent in the West by Kano at the turn of the century to help promote Judo. In Brazil, taught Carlos Gracie his art which in turn evolved to become what is now an internationally recognized martial art. During his tourney, Maeda challenged many wrestlers and boxers and gave exhibitions which sometimes included swordsmanship. It is unclear what type of kenjutsu Maeda was practicing and what the context of these pictures was, but it shows that some kind of exchange took place between Japanese and European martial artists.

Maeda fencing against a sabreur

Finally, many American fencers also tried their hand at kenjutsu. As we already saw in past articles and more in-depth in one which is soon to be published.

Taking a lesson from the past

The portrait that these men have left us is one of openness unaffected by childish rivalries or national vanity. Be they French, English, Japanese or German they were all there to learn, something which a true martial artist should never cease to do. Of all time, warriors were curious to learn different approaches to combat and we should be imitating them in this regard.

Special thanks to George McCall for some of the pointers in this article!

There was also the meetup in Cuba between Castello the elder (IIRC) and a kendoka.

Nice article, but could you please provide some sources, especially concerning Erwin Von Baelz?

Concerning Baelz you can read his memoirs which mentions all these elements. http://books.google.ca/books/about/Awakening_Japan_the_diary_of_a_German_do.html?id=1C-CAAAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y

Based on the kamae of maeda showed in the last picture and the knowledge of the partnership between Jigoro Kano and Sasaburo Takano in the early history of Kodokan, I can reasonably state that he was formed in a solid Kendo experience