By Maxime Chouinard

For years, the identity of the author of the 1790 broadsword manual “Anti-pugilism”, retitled “Cudgel-playing” in 1800, had puzzled researchers. The 1800 edition tells us that he would have been a certain captain G. Sinclair of the 42nd Regiment of Foot. Two George Sinclairs were found, both having served in the 42nd prior to 1790, but the problem that had many researchers stuck was that none of them was a captain.

Following a discussion on the topic with Xian Niles of Niles’ Fencing Academy in Halifax, I decided to go through the paper trail to see if the mystery could perhaps be solved. The result was, in my opinion, the discovery of the real Captain George Sinclair. As you will see through this article, the reason why his identity remained unclear until now is partly due to the intricacies of rank in the British army, as well as how officers- and also their descendants- choose to present it.

Will the real George Sinclair please stand up?

George Sinclair was born in 1727 in Durran, in one of the Northernmost region of the Scottish Highlands. The son of John William Sinclair of Durran, and Elizabeth Murray Sinclair of Barrock, both of aristocratic stock. 1

George was a descendant of the Fourth Earl of Caithness, and was said to be a descendant of King James V of Scotland, possibly through one of his illegitimate children, though I was not able to verify this claim2. This distant ancestor, real or not, was probably the explanation for the presence of the shield of the Kings of Scotland in his portrait, the centrepiece of James’ coat of arms.

George was commissioned as a lieutenant in the 42nd Regiment of Foot, or Black Watch, in August 1758. The date is important here, as in early July of that year the regiment suffered one of its most terrible defeats at the battle of Fort Carillon in North America. More than 300 men of the Black Watch were killed, and as many were wounded, trying to take the fort from the French, which was commanded by the marquis de Montcalm.

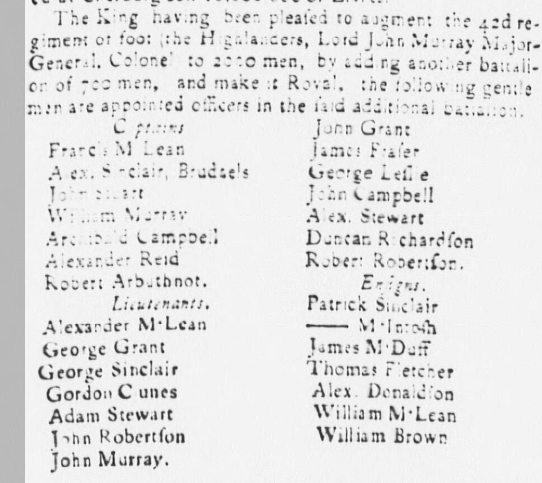

Since the Regiment was already due to receive a Royal status, the Crown felt obliged to help it rise from this severe blow. This is when Sinclair was brought in, along with 700 soldiers, to fill in the ranks of a second battalion while the first healed its wounds.3 To make up for the defeat at Carillon, the second battalion was then sent to invade the French colony of Martinique in January of 1759.

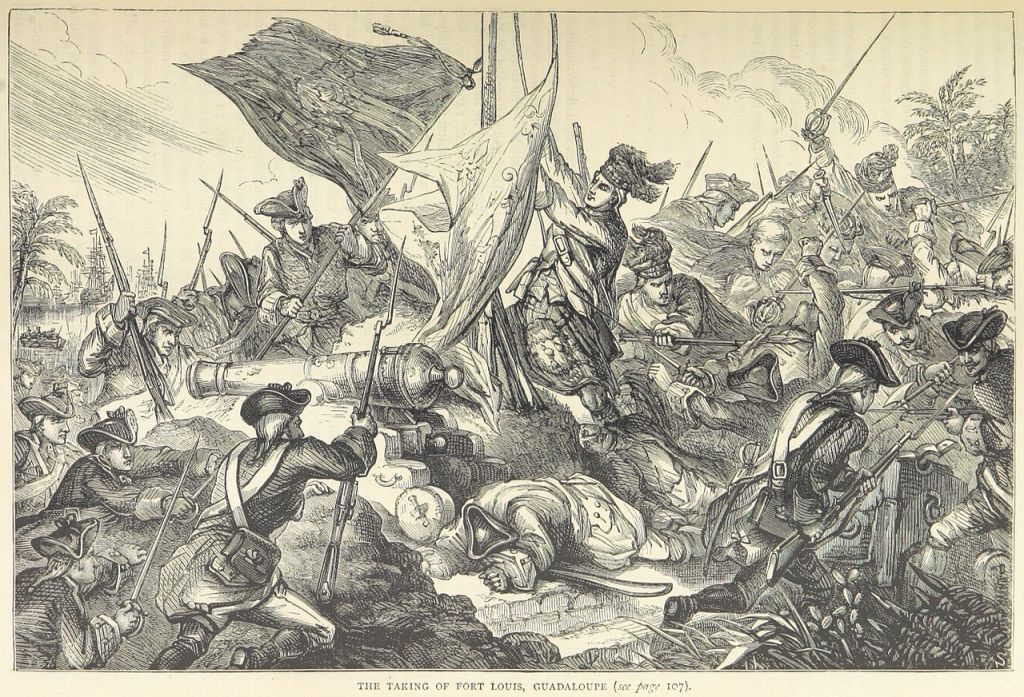

The expedition was initially not met with success, and so the British commanders decided to change their objective by setting their sights on the island of Guadeloupe instead. This proved a better choice, and the island fell to the British in may 1759. Yet, the victory was again costly for the regiment, especially with the addition of the various tropical diseases contracted by the soldiers.

At this time, there were two George Sinclair in the 42nd regiment, both of them lieutenant. One of the two was reported as wounded following the invasion, and by June one of them was reported dead. Not much is known of this George Sinclair, and trying to identify him further from such a small service record would be quite difficult. It isn’t clear at this point if this George died of his wounds, or if the survivor was the one wounded. What is certain is that the surviving George was then sent to “Crawford’s Regiment”.4

The name of “Crawford Regiment” is somewhat confusing at first glance, as this was the initial name of the 42nd when it was raised, but what we realize by researching further is that George was actually transferred to an entirely new regiment: the 85th Light Infantry (or Royal Volunteers) raised in Shrewsbury; the first Light Infantry Regiment to be created in the British Army, and formed by Colonel John “Crauford”, an officer of the 13th Foot.5 George was listed as being in Edinburgh in October of 1759 as a recruiting agent for the 85th.6 One can imagine that this transfer could have been given to him to help recover from wounds received in battle, or from a disease he would have contracted in the Carribeans. This transfer is the key to the problem that was faced in trying to identify him.

During his time in the 85th, Sinclair could have been involved in the Siege of Belisle, and the conflict between Portugual and Spain in 1762.

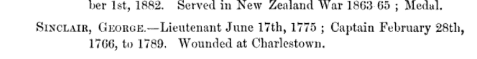

By 1763, with the end of the Seven Years War, the regiment was disbanded, and Sinclair was on half pay; but three years later he was promoted to the rank of captain in the 65th regiment of foot, then based in Ireland.7 In 1768, the regiment was shipped to Boston, where it stayed until the War of Independence.8 In 1775, it was involved in the battle of Bunker Hill. Sinclair was once more lucky in his misfortune, as the 65th incurred several losses in the engagement, which he managed to survive. The regiment was sent back home in 1776, but some of its officers were sent to other regiments. It was probably the case of Sinclair, who is listed as being wounded at the siege of Charlestown.9

The regiment was then shipped around the globe. In 1782, it was sent to Gibraltar, and then to Canada in 1785; starting in Quebec City before moving to Fort Niagara in 1786.10 In 1789, George Sinclair retired and left for London.11 He passed away in November of 1790, in his house of Kensington Square, at the age of 63.12

Having no issue, George left most of his belongings to his nephew, Patrick Sinclair, a captain in the Royal Navy.13 Curiously, in his will George refers to himself not as a captain, but a lieutenant-Colonel; a title that is also repeated in newspaper notices14. In the army list of 1782, George indeed has an army rank of lieutenant-Colonel, but a regimental rank of captain. This indicated that he could be called on to replace the regiment’s current lieutenant-colonel if need be. Even though he was still a captain within his regiment, this gave him the right to be referred to as a lieutenant-colonel in certain settings.

Will of George Sinclair, Lieutenant Colonel in His Majesty’s Army and Captain in His Majesty’s Sixty Fifth Regiment of Foot of Pall Mall , Middlesex. 17 December 1790. National Archives, Kew, PROB 11/1199/126

To summarize, it makes little doubt that Captain George Sinclair of Durran was the author of Anti-pugilism. He is one of the two George Sinclairs who served in the Black Watch before the book was published, and obviously the only one who survived up to 1790, and of course the only one that reached the rank of captain. As he passed away at the end of that year, it is possible that the book was published before his demise. It is also possible that his nephew had it published, and that his son, James, had the book republished in 1800 under the name “Cudgel Playing”. Patrick had died in 1794, during the capture of Port-au-Prince, and in 1800, James was a lieutenant in the Royal Marines. He also passed away shortly after this, in 1801, during a naval battle with a French sloop, leaving Patrick’s daughter, Catherine, as the only living heir of the Sinclairs of Durran.

Then why a Captain of the 42nd?

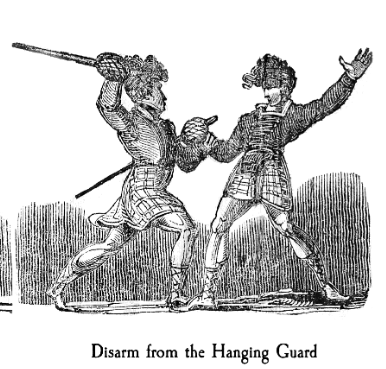

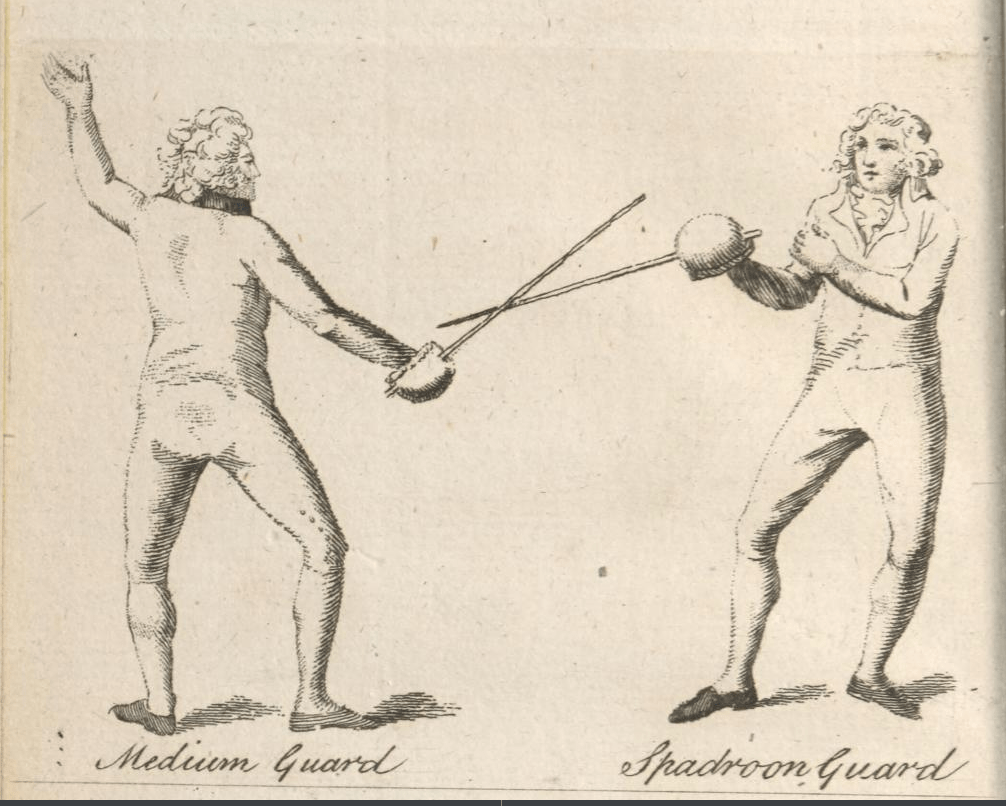

One question you may ask yourself is why Sinclair decided to sign the book as a captain of the Black Watch, instead of a lieutenant colonel of the 65th, or even a lieutenant of the 42nd? The explanation is quite simple: he never did. Indeed, this assertion was only made by whoever republished the manual in 1800. The 1790 edition makes no mention of the 42nd regiment, the author being simply referred to as a “Highland officer”. George was indeed a Scottish Highlander, and an officer. Even the illustrations, penned by the famous British cartoonist Isaac Robert Cruikshank, show the two subjects in fashionable English civil garbs, while the 1800 edition has characters dressed as highland soldiers, and other military uniforms. While it impresses the necessity for soldiers, and particularly sailors, to learn the use of the broadsword, the first edition is resolutely civilian in tone, introducing itself on the frontispiece as a method to defend oneself against “Johnsonians, Big Bennians, Mendozians” and other fisticuff afficionados of the era; hence the curious title “Anti-pugilism”.

His estate may have considered that the book needed to better sell us on the author’s Highland origins and military service, even though the title still shows curious restraint over its main subject. The original edition certainly strikes a much humbler tone, especially in its visuals.

Presenting George as Lieutenant-Colonel of the 42nd would have been quite inexact, and the 65th regiment- although it was truly the regiment where he spent the most of his career- was a fairly run of the mill British regiment, and as the British crowd by then strongly associated broadsword fencing with the Scottish Highlands, the famous Black Watch was probably seen as the best marketing choice for the book. It is also quite possible that George’s family was aware of their great uncle having been an officer in the 42nd, but was maybe not quite aware how short that time was, and that his promotion to the rank of captain happened at a later time

It must be said that the social context between the two editions was quite different. in 1790, Britain came out of the American Revolutionary War- and the associated conflicts with France, Spain and the Netherlands -somewhat bruised and battered, while a third conflict with the Kingdom of Mysore-the previous two having ended in failure- was still ongoing. It’s possible that a book on broadsword fencing needed a less bellicose tone, while one published in 1800-at the height of the War of the Second Coalition- could be marketed with a more militaristic one.

The change of artwork is also a bold one, though maybe not that surprising. The quality of the illustrations definitely drops in the second edition, not benefiting from Cruikshank’s skill anymore, but comparing the title plates, when considering the context explained before, makes the switch probably understandable. The 1790 frontispiece is certainly detailed, but the action depicted is quite odd looking, and clearly not the right choice if someone wanted to sell the book to military men. The 1800 fanciful sketch of Sinclair is so over the top as to be gaudy, but it does fit the objective.

There is a good chance that Sinclair’s manual may have been published after his death, or at least shortly before. The clue is again found in the choice of illustrations. It is quite curious that Sinclair chose to have portrayed only the guards which – by his own advice- are the least useful. The outside and inside guards, those to be relied on, are nowhere to be found. This leaves the feeling that there was not enough time to have them finished for the publication.

Captain Sinclair the fencer

Now that we have established who the author was, we can ask where he learned to fence. Obviously, in thirty years of service, the occasions may have presented themselves in a variety of ways. It could have been during his time in the 42nd, though it was surely an incredibly short one. It could even have happened prior to his service, when he still lived in Scotland. One possibility to consider is that he may have actually learned this art from his time living in Boston. Indeed, we know that certain broadsword masters held lessons in the city just prior to the Revolution. Among them was a fellow veteran of the Seven Years War, Donald McAlpine, of the 78th Fraser Highlanders.

Sergeant McAlpine moved to Boston in 1769, just a year after Sinclair, who would have lived there until 1775. He immediately set up classes in fencing as well as French lessons. The image above was taken from the diary of one of his students, a young Sir Benjamin Thompson, count Rumford. It is unfortunately the only part of these notes that have been found so far, as they were reproduced inside a biography of Thompson in 1871.15 It appears that the New Hampshire Historical Society came to possess it, as it was donated to them by Joseph Burbeen Walker. It was still held there by 198116, but when I contacted the society a few years ago to enquire, it seems that they were unaware of its whereabouts. The diary may not contain a prodigious amount of information, but I do hope that a local historian may be able to help the NHHS find this missing diary, which may simply lay dormant in some archival fonds.

This single snapshot of McCalpine’s teachings does illustrate a parallel with Sinclair, who describes and illustrates his stance and his medium guard in a very similar way.

That said, the guards presented by Sinclair are mostly all familiar to previous authors like Miller or Lonnergan, though the hand is held much lower than either of them. It is perhaps closer to what Page describes, except for the addition of the medium guard, and the fact that the feet are mostly always in the same position, and do not change in between inside and outside guards. This low hand position is very reminiscent of earlier continental authors like de la Touche or McBane, who relied on the medium guard (ancient tierce) for their cut and thrust methods of fencing. Sinclair mentions how it is often suggested by others to straighten the forward leg in this guard, which is also found in most of these methods. This hints at a remnant of ancient Franco-Italian fencing concepts in British and Scottish fencing, concepts that had disappeared in France by the early 18th century.

Sinclair’s work is an important piece of British fencing history, as it represents perhaps the last vestige of an older style of broadsword fencing, before the hegemony of the Angelo family took over the country. Wherever Sinclair may have learned to use a broadsword, his manual is truly an intriguing piece of fencing history, and with the author now identified, we may be able to better situate it in the general corpus of 18th and 19th century martial arts.

Bibliography

- Henderson, J. (1884). Caithness family History.. ↩︎

- Patrick Sinclair – more than Nelson. (2019, December 2). More Than Nelson. https://morethannelson.com/officer/patrick-sinclair/. ↩︎

- Leeds Intelligencer – Tuesday 22 August 1758 ↩︎

- Richards, F. B. (1911). The Black Watch at Ticonderoga and Major Duncan Campbell of Inverawe. ↩︎

- British Light Infantry Regiments. (n.d.). https://www.lightinfantry.org.uk/regiments/ksli/shrop_85foottl.htm ↩︎

- Caledonian Mercury – Monday 01 October 1759 ↩︎

- List, A. (1766). A list of the general and field-officers, as they rank in the army [&c. The annual army list, with variations in title, orig. issued “by permission of the Secretary at war” by J. Millan, and afterwards issued by the War office]. ↩︎

- List, A. (1769). A list of the general and field-officers, as they rank in the army [&c. The annual army list, with variations in title, orig. issued “by permission of the Secretary at war” by J. Millan, and afterwards issued by the War office]. ↩︎

- Raikes, G. A. (1885). First Battalion, formerly 65th (2nd Yorkshire, North Riding) Regiment, from 1756 to 1884. ↩︎

- 1st BN, the York and Lancaster Regiment: Service. (n.d.). https://web.archive.org/web/20071213223126/http://www.regiments.org/deploy/uk/reg-inf/065-1.htm ↩︎

- Raikes ↩︎

- Local Studies and Archives-Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea; London, England; Kensington and Chelsea Parish Chest; Reference: MS63/9656 ↩︎

- Will of George Sinclair, Lieutenant Colonel in His Majesty’s Army and Captain in His Majesty’s Sixty Fifth Regiment of Foot of Pall Mall , Middlesex. 17 December 1790. National Archives, Kew, PROB 11/1199/126 ↩︎

- Hereford Journal – Wednesday 24 November 1790 ↩︎

- Ellis, G. E. (1871). Memoir of Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford: With Notices of His Daughter . . . Published in Connection with an Edition of Rumford’s Complete Works. ↩︎

- Brown, S. C. (1981). Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford. MIT Press (MA). ↩︎

I see by this blog post that you’re probably still alive. Not sure if you still sell swords. Very interesting information. It’s these sorts of deep dives I’ve had to do while researching US Naval swords.